In Shakespeare’s famous play The Merchant of Venice these beautiful lines flow:

In Shakespeare’s famous play The Merchant of Venice these beautiful lines flow:

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.

Lately those lines have been resonating in my head within two primary contexts: 1) my practice of Quakerism, a religious journey I’ve recently started, and 2) my practice in Quality Assurance, a profession I’ve been in for the last 30 years. As I wonder about the meaning of “quality,” I ask myself, “if I do not believe in the direction I choose with all my heart and soul, how can I explain it to someone else?”

Shakespeare so eloquently makes his point in two lines, so why do we create thousands of pages and hours of confusion trying to do the same thing? Can one indeed sort through mounds of complexity to select quality and apply it to the practice of both one’s faith and one’s work, or should one just let it flow? Silence works really well.

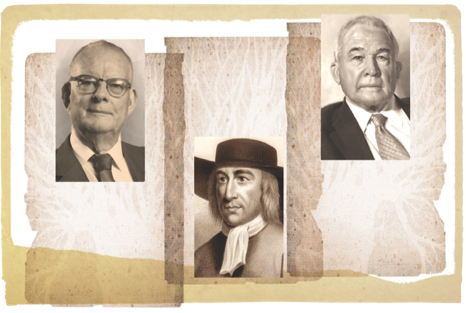

I received some insight into this dilemma from attending a leadership workshop offered by Boulder (Colo.) Meeting, of which I’m a relatively new member. The meeting was having leadership issues with a few of the many volunteer committees that run the place. We were fortunate to receive a visit from Arthur M. Larrabee, the general secretary of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and a frequent presenter on leadership skills and Quaker process. Larrabee is a lawyer who founded the Larrabee, Cunningham & McGowan law firm, though he no longer practices. I have attended many leadership workshops for my work, but since this one was in a different setting, and I was a newly convinced (i.e., inexperienced) Quaker, I signed up with a completely open mind.

One of the questions I’m most frequently asked about both my Quality Assurance work and my Quakerism is “Yes, but what does it / do you / do they do?” That can be a tricky question to answer in either realm, but as the “Quality of Quality” and the “Quality of Quakerism” become increasingly entangled in my life, I find so much common ground.

The books available on Quality Assurance and quality control could bury Europe in a ten-foot layer of paper. Quakers have been writing books, testimonies, faith and practice interpretations, pamphlets, and journals for far longer than Quality experts, and often (though not always) in a far less strident tone, but these texts, too, can be contradictory and confusing. There are Quakers who advocate programmed worship and those who advocate waiting worship; there are (that I know of) Conservative, Liberal, Evangelical, Universalist, Gurneyite, and Nontheist Quakers—and every author seems to write in the sure and declared conviction that his or her stance is right and the others are misguided.

I see many parallels between the pursuit of Quality and being a Quaker. Both are centered around people and processes, and both promote the documentation and sharing of best practices. In both cases, successful practice means embodying a simple set of principles in the daily exercise of one’s work or life. Where both endeavors most often fail is when there is wide disparity and contradiction among what is said, what is written, and what is really practiced.

When I do a Quality Assurance due diligence analysis for a company, I tend to find that the program utilized takes one of two very different approaches. The most common—and generally the least successful—is what I call the compliance approach that looks from the outside in. The second is the holistic approach that depends on everyone involved in the process internalizing and following a set of core beliefs.

The compliance approach begins with someone in the top echelons of management, often accompanied by weighty documentation veiled in acronyms. Compliance is documented by reams of checklists and forms, all signed off by people in a lengthy chain of command, most of whom have not looked at the actual work. Compliance is enforced by auditors, who look at what has been noted on the checklists and forms and determine if the work was done correctly or not.

The holistic approach begins with the belief that quality originates from teams of individuals who share a commitment to the spirit of quality. It manifests as these teams of people work harmoniously together to constantly improve both the quality of the product and the quality of life within the organization. A core belief is that if you notice an aspect that is not functioning correctly and therefore negatively affects the spirit of the company, you have a mandate to do something about it.

Quality control and quality management techniques using the holistic approach were pioneered by W. Edwards Deming in the late 1930s. In my view, Deming wrote about the same concepts as Quaker founder George Fox—the former applying them to one’s working life and the latter to one’s spiritual life.

When I was starting my career in Africa, much of the work focused on looking for better ways to do things despite the scarce resources we had. My team and I came across the works of Deming, and there we found our “quality Bible.” Deming’s famous “14 Points for Management” were our guiding commandments. I discovered the most important of these points to be #8 “Drive out fear” and #12 “Remove barriers to pride of workmanship.”

So, to expand upon Shakespeare’s words, “Quality is not strained. It droppeth as a gentle rain, vanquishing fear and awaking pride of endeavor.”

In quality assurance consulting and the administration of a Quaker meeting, due diligence is used for problem solving and often focuses on “whodunit.” When we met with Larrabee, we had a long list of concerns for discussion, including how to handle a “rogue leader.” We expected Larrabee to declare judgment, but instead, he began by asking, “What is the function of the clerk?”

He led us to build the logic of the answer ourselves: the clerk’s role is to protect, nurture, and grow the spirit of the meeting (or committee). Light bulbs went off in my head. The focus of our attention suddenly shifted from problems to solutions.

The clerk of a Quaker committee or meeting is also the facilitator of a decision-making process that calls for participants to contemplate in silence what each speaker has said before the next person speaks. Encouraging periods of silence is far more productive than allowing the intrusion of verbal noise, and leads to much better spirit as well. A Quaker meeting has its books of Faith and Practice, and its list of testimonies, but as Larrabee led us to discover, right decisions come not from reading those “manuals,” but from hearing and heeding the spirit of the meeting.

A company that believes compliance is the sole way to go will soon be lost, while one that believes in the spirit of quality will always survive, often in spectacular ways. In 1980, I worked with two airlines in Dallas, Texas, that had dynamically different operations. Braniff Airways was large and arrogant, with many layers of management. We spent nine months there just setting up the service call team.

On our last day with Braniff, we asked the receptionist if there were other airlines based at the same airport. She directed us across the Dallas Love Field tarmac to Southwest Airlines, a company so small that it seemed unlikely they would remain in business very long. We walked into the office without an appointment and met the head of aircraft maintenance, who directed us straight back to the office of then-CEO Herb Kelleher. It was around Easter and Kelleher had just returned to his office after wishing passengers and staff a happy Easter—dressed in a pink rabbit suit and smoking a cigarette.

The discussion that followed was all about the spirit of the company and what we could do to help. Arthur Larrabee and George Fox could have attended that meeting and been perfectly at home. Secretaries, flight attendants, and ground crew at Southwest had (and still have) more power to make things right in their company than the executive directors in the Braniff boardroom. Look at the results today: Braniff is long gone, and in 2011 Southwest carried the most domestic passengers of any U.S. airline and marked its thirty-ninth year of continued profitability.

The quality of a company is built on what is practiced every day. There may be many manuals to read, but success depends on employees having those beliefs written in their hearts. If you think that sounds like what Quakers should do, I agree. You can read the Bible, along with all of the journals and letters of George Fox, but it is not worth a hill of beans if you do not walk the walk, believe till it hurts, and live out your testimonies every hour of every day.

This is the best and perhaps the only analysis I’ve ever read on quakerism and quality assurance. Lots of insights.

As a former friend and current quality practitioner, the article was an eye opener.

Great job.