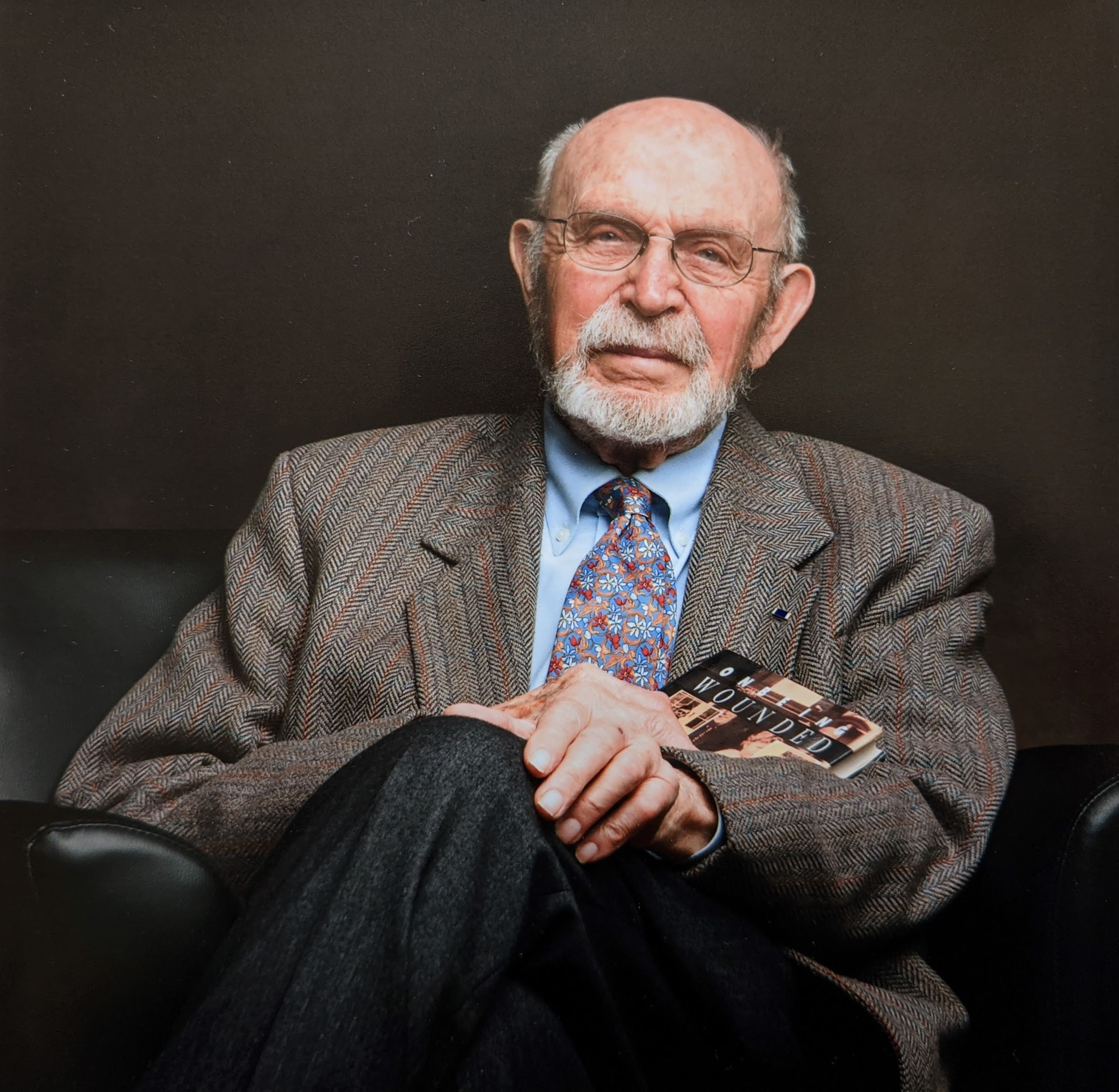

The Power of Narrative to Heal

One of the seldom-discussed consequences of war is what I term “the shame of combat,” a destructive emotional condition arising from acts and emotions experienced in direct confrontation with an enemy. I share my own experience of this condition and the ways I came to terms with it after World War II. I also hope that recognizing the shame of our acts of war might help America pause in its ruthless effort at world domination through war instead of diplomacy and take heed of the Quaker call: “War is not the answer.”

This discussion is of enormous importance because the United States, within its continental boundaries, has had no direct experience of war since the end of the Civil War in 1865. Yet in that time, particularly since 1941, its soldiers have waged almost constant warfare all over the world. If shame is one of the most significant emotional problems the returning soldier faces, it is time for the nation as a whole to both recognize this characteristic of modern warfare and to assume responsibility for this burden that it places upon its combatants. The emotion of shame is, quite simply, part of a combat soldier’s emotional baggage when he or she comes home.

My personal shame after I was wounded in World War II rose from three conditions, all of which merged into a crippling emotional state. First, I was only in combat for one day, because as I fought in an assault on the Germans while in France, I suffered injuries so severe that I was sent home. Because I served for such a short time, I believed for years that I had never proved myself as a man. Second, wounded by shrapnel in the head, the buttock, the lower back, and the pelvis, I felt shame about my damaged body. The buttock wound in particular exacerbated my shame: Would those at home believe I had been running from the enemy? And third, I had a father who told the local newspaper I had only been at the front for a short time, and my best friend’s father wrote a letter saying that I had been at the front for such a short time that it had hardly been worthwhile for me to be there at all.

Together, these scorched my mind and my emotions and led to a collapse of my self-esteem that lasted for decades. That collapse was so intense that it led to an attempted suicide.

I now know that shame was at the core of my collapse and the attempted suicide. Shame, though seldom discussed, may also be one of the main causes of the large number of suicides we have in our armed forces today. Statistics vary over time, but the 2024 report from the Veterans Administration counts over 17 veteran suicides on average every single day.

Shame is common to many soldiers during and after combat and is one of the most troubling reactions to war and one that they must deal with throughout a lifetime. It is also the one least often admitted and the one almost never talked about.

Beside one’s own behavior, shame can come from the actions of one’s squad or platoon, company, battalion, regiment, or division. And, finally, the shame may rise from the simple fact of being at war and experiencing its horror, from the acts of one’s nation.

The shame of the individual soldier rises from acts of commission and acts of omission. Acts of commission include injuring, wounding, or killing a comrade accidentally; humiliating prisoners of war (the bag over the head); torturing (a rifle butt in the face); killing an enemy combatant; or wounding oneself to avoid combat. Acts of omission include refusing to fire; or firing one’s weapon while avoiding shooting with killing as the purpose, betraying one’s comrades; refusing to go to the aid of a comrade; skulking—hiding—staying just behind the front where the firefight occurs; and finally, desertion, fleeing the front for safer places (50,000 American soldiers in Europe did it in World War II, with only one shot by a firing squad).

The shame of the unit comes from instances such as the massacre of civilians at My Lai in Vietnam; the surrender of 6,000 members of the U.S.’s 106th Division at World War II’s Battle of the Bulge; the flight from combat as happened to the Union forces at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861.

The shame of the “situation” is simply the shame of war’s reality. For war is finally only about one act: killing. And killing is for most men and women a morally reprehensible thing to do. We are trained from childhood to believe that killing a fellow human is wrong, no matter our religious tradition. Quakers do not have a unique teaching on this matter, although we are known in particular for our peace testimony and for protesting against war. And we—I!—did it: took that life, one of the few absolutely irreparable acts of destruction a human can commit and one of the few irreparable acts of destruction we remember for a lifetime, made even more despicable if that victim is a civilian, a child, or a woman; even more haunting when the killing or the wounding occurs from a distance, by bomb or by drone.

We have built a vast deposit of shame from war that now lies heavy over our sweet earth and is so seldom seen or admitted. Recognizing it and dealing with it is one of the most important acts of reconciliation that might help our wounded soldiers and our wounded world today.

And since there are no manuals or guides to lead one to surcease, I offer how I slowly faced the problem of my shame, began to understand it, and slowly resolved it—long before there was adequate professional help for the emotional wounds of war.

In my experience, recuperating from the psychological effects of war involves lonely acts of individual healing done by soldiers—as they had in so many wars before—through a variety of strategies, many times unconscious. One strategy that I believe is neglected is the use of narrative: the discovering of a story that lets us make sense of what had happened to us, a narrative that gives our war experience meaning and makes us whole and carries us beyond the reach of shame. In those stories, we reconstructed ourselves; we healed what had been wounded and broken.

Friends, family and children, career, and community support—these were the common strategies available to us and how we dealt with our shame after combat in World War II. When I first returned from war, I found community primarily with other ex-soldiers, but later in my life, I found community in addition through deep involvement in a Quaker meeting.

Yet that path of reconstruction of a life for me and for other ex-combat soldiers of World War II also needed to be supported by a governing narrative. By this I mean a personal story, something more than the kind of storytelling one finds in movies or in books, although the depiction of war in the popular media can have an enormous impact on how we think about combat.

In 1945 and 1946, when we came home, we called upon centuries of accumulated tales of war, for it was through these stories that the warrior of history had made sense of all that had happened in combat. In the fine book by William Pfaff, The Bullet‘s Song: Violence and Utopia, one reads this statement about war’s attraction: “Until modern times, wars were consistently recounted in the primordial literary form of epic, with a hero, a quest and ordeal, tragedy or success, and the acquisition of wisdom.” One only has to think of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and the histories and tragedies of Shakespeare to recognize the kinds of stories men once made of war, in which the heroes triumphed, men survived agonies, and war was celebrated as the ultimate challenge of manhood.

Following the Industrial Revolution, however, the nature of war slowly changed. No longer did the individual engage in combat on a field of honor but instead witnessed the murderous and impersonal horror of killing at a distance with the bullet and the bomb. And with that transformation, the stories told of war changed.

Perhaps the first and most powerful restructuring of the war experience was Goya’s Disasters of War, etchings made between 1810 and 1820 of the contemporary war in Spain. They give a powerful sense of war’s horror. No longer is there glory or any tale of courageous manhood in war’s train.

Words as a way to present a revised narrative of the war experience as horror were beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. The first realistic descriptions in English of the war experience were in the 1867 writings of John W. Deforest in his Miss Ravenel’s Conversion from Secession to Loyalty, about the U.S. Civil War. Before him, of course, in Europe, Stendahl wrote La Chartreuse de Parme, and Tolstoy delivered Sevastopol Sketches, then War and Peace. In addition, Steven Crane and Ambrose Bierce, American fiction writers, continued the path of realism in writing of the Civil War in the United States.

After this, in World War I, World War II, Vietnam, and all the small wars since, a torrent of words, photographs, and movies expressed this realistic, often cynical and grim, view of war and its impacts.

Implicit in the realism was the fierce moral judgment that war was fundamentally wrong, shameful: wrong to kill, wrong to fight in such an impersonal and industrial way, no longer heroic or even patriotic. In World War I and World War II, the emerging narrative of conscientious objection also formed around this view of war as morally wrong. In the United States and England, there were 4,000 conscientious objectors in the First World War and 50,000 in the Second, many of them Quakers. (See in the December 2006 issue of Friends Journal an article written by John Mascari, “U.S. Conscientious Objectors in World War II.”)

At the same moment, in the 1920s and 1930s, the new genre of the war movie introduced its own narrative in perhaps the first (and maybe still the best) antiwar movie of all time: 1930’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Movies since then have become, perhaps, the most important medium for returning to the stories of old, presenting war as epic and the combatant as a hero to be worshiped: sometimes killed, sometimes victorious but always, in his own way, triumphant.

Thus in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in art, literature, photography, and film, the story of war evolved into totally new kinds of narratives told with new forms, some emphasizing war’s horror; its lack of heroic qualities; its industrial nature; its existential destruction of the human potential; and always its moral failure, always its shame, while others continued with the epic frame of war as the apogee of human experience.

It took me long decades to discover a narrative that healed my shame. I recovered only when I returned to France in 1984 and rediscovered the place of my wounding. As I wrote in On Being Wounded, I “was filled with a terrible and fierce pride for that boy,” the boy I once had been. Vivid memories came back to me of the chilly reception I received from the men in my patrol when I arrived as a replacement, signaling that I was a stranger: not one of them.

The shame that I had carried for 40 years had almost destroyed me, yet now it began to evaporate. This new story, one of understanding what that boy had done while totally alone in combat, without a single friend, freed me finally when I was almost 60. That new narrative of what I experienced while in combat had so many liberating revelations. I had not been a coward: I had done what few ever do; I had laid my life on the line for something in which I believed, for I had a calling that I could not resist: leaving a safe billet to transfer to a combat unit. Fighting the injustices of Hitler’s Nazis overrode my mother’s teachings that “thou shalt not kill.”

Also, I had finally learned over those long years that when a woman really loved me, the scars of war scarcely reduced that love by an iota. And, as for the opinions of my father, why, they were nothing. My father had never experienced war. His judgment of me should have been meaningless. While I was in France, these insights at last came to me only when I turned and faced the past head-on, able to reconnect with whom I had been before I was so badly wounded.

Only when I discovered this new narrative did I free myself of my personal shame. In so many ways, my personal life changed, exploded into a fresh experience of joy, almost as if I were young again and had never been wounded. Once more I wrote, found my true voice, and published to acclaim. I fell in love, no longer shrouded with shame. I found new meaning in the peace testimony: that inner peace must precede my outer expressions of peacemaking. I had the courage, as part of an American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) speakers bureau, to talk with confidence and conviction about the moral depravity of war at the U.S. Air Force Academy. In what felt like an opportunity to live the Quaker teaching of speaking truth to power, I agreed to be the lunchtime presenter at a Retired Army Officers’ club. Despite the lukewarm reception, I wasn’t daunted.

My tragedy is that it took me 40 years to discover a new narrative by which to live, beyond my personal shame of combat: 40 years of pain. I needed to create a narrative that made sense of what happened in combat, a story that knit the time in combat with the years before and the years after, that opened up an understanding of what that time spent in warfare did to my soul: the shame, the pain, and the destructive emotions that lurked repressed and unaddressed below the surface. The healing narrative is one that combines these difficult parts of the story with the redeeming parts.

These four efforts together—the recognition of shame, the search for personal strategies for survival, the refusal to carry the shame of the nation or the shameful behavior of others, and the discovery of a narrative that heals the soldier’s heart and opens a way to a future beyond shame—these four together may ease the soldier into a new and rewarding life. And, in so doing, I also hope that we, as individual soldiers, having healed our personal shame can then, perhaps, help the nation become aware of and then heal its national shame.

Thank you Edward W. Wood Jr, for your powerful rendering of your personal journey of living with the shame of war. It is a story I’ve never heard before. It’s a story that has profoundly moved me. I’m so sorry for the 40 years shame held sway over you. And I am so grateful that you finally faced it head on and reaped healing and release. Thank you again for such an itimate sharing of your very soul.

As a psychologist at the VA Medical Center, I heard many stories that changed me from a theoretical pacifist to a flesh-and-blood hurting pacifist. A quarter century after retiring, I thought I had healed, but I’d only forgotten. This article knocked the scab off.

Sometimes when a patient would tell me how war had changed them, I’d encourage them to tell others–the home front–what it was like. They’d usually say, “You wouldn’t understand if you weren’t there.” I know that is true; there’s a difference between hearing about it and living it. But if more of us heard about it from those who lived it, would we allow our President to send people into battle? We’ve just sent the US Navy to blow up boats in the Caribbean; the service members who pulled the trigger can reason with themselves that they had to do it because they had taken an oath to obey orders, but in their dreams, and in the years after they leave the service, the memory of what they did may come back to haunt them. I know, because I had the privilege of listening to their stories.

As I hold Friend Wood in the Light, I feel I must respond to his statement “…The United States, within its continental boundaries, has had no direct experience of war since the end of the Civil War in 1865”. Should Friend Wood ever venture to our West Coast, I invite him to tour Fort Stevens on the coast of Astoria, Oregon. On June 21, 1942, a Japanese submarine, commanded by Akiji Tagami, surfaced and fired 17 shells at the fort. The shots proved harmless and no injuries were reported. As the fort could not obtain an exact bearing on the sub, it did not return fire. The sub then went to the outside of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and fired more shots before making a final destination of Alaska. In the meantime, Japan was sending balloon bombs on the air currents to the West Coast which, upon landing, exploded into firebombs in hopes of defoliating our rich vegetation for more accurate attacks. Such a bomb came down in another part of Fort Stevens, killing an entire class of young children on a field trip, for which a memorial has been erected in their memory.

This is really an extremely important and profound issue. I’m not sure I have the right to comment on it. I dare only remark that shame is perhaps one of the most human feelings, and morality and ethics are what sets a human apart most from other beings. War, in addition to the monstrously immoral obvious things, is also a triumph of lie – a colossal and absolutely shameless one. And that’s why, great respect to Mr. Wood, a strong-minded and brave man, for his truthful narratives about the war and his selfless service in the name of peace.

It is sad that there will never be the opportunity to communicate with this wonderful person ever again.

This essay is incredibly moving and courageous. Your willingness to speak openly about the long-lasting emotional and spiritual wounds of combat creates a space for understanding and compassion that many veterans desperately need. The thoughtful way you reflect on shame, healing, and personal transformation is genuinely inspiring. This isn’t just a story—it’s a lifeline for others who may be struggling with similar burdens. Thank you for sharing such deeply personal insight.