What Climate Activists Can Learn from the Movement to Abolish Slavery

Disruption of our climate system is the great moral issue of the twenty-first century. Over the last 200 years, the United States and Europe have grown rich while destabilizing our climate with carbon pollution. Yet it is poor, populous countries, which benefited little from industrialization, that are suffering the most. Bangladesh and Pakistan are already experiencing worsening floods, droughts, and tropical storms. People in the Sahel region of Africa are caught in climate-caused conflicts over water. Even in developed countries vulnerable people are threatened, as occurred when the storm surge of Hurricane Katrina flooded the poorest neighborhoods of New Orleans.

As people of faith, we are called to answer the moral challenge of climate disruption. All faith traditions believe the natural world is sacred, and call us to care for the poor and weak. To answer this challenge, we must fundamentally alter our relationship with the earth. It is a daunting, urgent challenge, but we can find inspiration from the movement that ended slavery 200 years ago.

Abolitionism was fundamentally a religious movement. It began in seventeenth-century Britain, led by Evangelical Christians, Quakers, Unitarians, and Methodists, who prevailed by changing the moral landscape. Before the abolition movement, slavery was viewed as a relatively benign institution in a hierarchical society; Africans were rarely considered equal in God’s eyes. By 1807, when the British Parliament abolished the slave trade, slavery was widely considered a sin so horrid that failure to end it risked eternal damnation. The story of this moral transformation shows us that radical change is possible in our time.

The 1700s were a time of revolutionary change. Evangelism, with its message of hope and salvation, was on the rise. Secular philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that individuals had inalienable rights. Scientists like Isaac Newton offered a new vision of the universe. The American Revolution made individual freedom the source of government power. It also changed the economics of slavery because it cut in half the monopoly market for West Indian sugar. The French Revolution destroyed traditional social hierarchy, and the Napoleonic Wars that followed further restricted trade in slaves and sugar. The successful slave revolt in Haiti terrified the planters, but temporarily boosted the sugar business by eliminating a large French competitor.

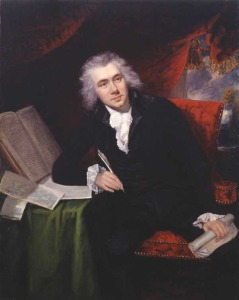

Abolitionists made full use of their moment in history. In 1787, British abolitionists formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, known as the London Committee. Thomas Clarkson, a tireless organizer who documented the horrors of the slave trade, and Olaudah Equiano, a freedman who provided invaluable firsthand knowledge, were both involved from the beginning. Clarkson recruited William Wilberforce, an evangelical member of Parliament, that same year.

Wilberforce was a rarity among abolitionists because he was a wealthy, white, male Anglican, and therefore could be in Parliament. Yet in the 1790s, the electorate was so limited that Wilberforce’s Yorkshire constituency, the largest in the House of Commons at the time, had only 2,500 voters. By and large, abolitionists had little political power. Most of them could not vote because they were women, Africans, or did not meet the property requirement for white men. Even a wealthy, white male abolitionist like the Quaker pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgewood could not serve in Parliament because he was not a member of the Church of England.

Powerful economic forces opposed abolition. When the London Committee first met, the slave trade represented 80 percent of British foreign trade. Sugar was an estimated 30 percent of the domestic economy, and the British government depended on revenue from the duties on sugar. West Indian planters, who had enjoyed a government monopoly for 200 years, were conspicuously wealthy. Their lobby, like the fossil fuel lobby today, won favorable tax treatment for their industry. They argued that sugar contributed to the British economy, much as the today’s fossil fuel lobby claims coal, gas, and oil are essential to our economy. The British army and navy protected sugar plantations and shipping, just as oil companies today rely on the American military to protect their interests in the Middle East. Adam Smith, the great economist and advocate of free trade who lived during the abolition movement, argued that Britain would be more prosperous if it abolished the sugar monopoly and ended slavery. Most modern economic historians believe Smith was right, but Parliament accepted the sugar lobby’s argument in the 1790s.

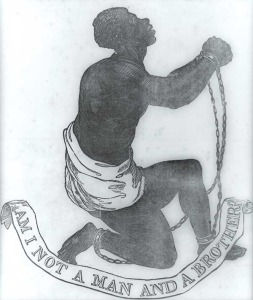

Today climate activists employ all of the tactics used by the abolitionists. Abolitionists published reports on the conditions and death rates that slaves endured during the Middle Passage, and they distributed vivid graphics, like the diagram of slaves packed into the slave ship Brookes. Today scientists and economists produce voluminous reports, and we all recognize Al Gore’s graph of rising carbon dioxide levels. Abolitionists publicized their message in newspapers and libraries, which had proliferated in the 1700s, just as we use the Internet and online videos. Josiah Wedgewood created a movement logo, a kneeling slave with the slogan “Am I not a man and a brother?” which is still recognized as a symbol of the abolition movement. Women boycotted sugar, spreading the abolitionist message to their friends and families every time they served tea without sugar. Today we talk of fossil fuel divestment. Finally, the London Committee built a network of local abolitionist societies that organized huge petition drives.

Wilberforce first introduced a bill to end the slave trade in 1789. In 1792, abolitionists submitted 400,000 petition signatures to Parliament in support of the bill. An astonishing 4 percent of all Britons, including women and working people, who would not be able to vote for another 100 years, publicly opposed the slave trade. To match that achievement in the United States today, climate activists would need to submit 10.5 million petition signatures to Congress.

Wilberforce introduced his bill seven more times. It usually passed Commons but failed in the House of Lords. The sugar lobby, playing to fear spawned by the French and Haitian Revolutions, persuaded the Lords that abolishing the slave trade would lead to emancipation and expanded rights for the British working class, which was more change than the Lords were willing to accept. In the face of these setbacks, the London Committee suspended its organizing efforts after 1792 and did not meet again until 1804.

In 1806, another abolitionist member of Parliament, James Stephens, devised an ingenious attack on the slave trade. British slave traders used American vessels during the Napoleonic Wars to evade a prohibition against trading with France. Stephens proposed an amendment to the Navigation Act that prohibited use of neutral ships to trade with the enemy. His proposal made no mention of the slave trade and passed easily, but it dealt the trade a crippling blow. With slave traders virtually out of business and West Indian planters undermined by a glut of sugar after 1800, Wilberforce’s bill finally passed in 1807. It had taken 20 years. It took another 25 years and a slave uprising in Jamaica to abolish slavery itself.

The abolition movement achieved far more than “merely” ending legal slavery. It changed morality. Although slavery still exists today, it is universally considered morally repugnant. Abolitionists also gave us a template for modern reform movements that has been used by socialists, unions, suffragettes, civil rights movements, and the Arab Spring. Each successive reform movement has expanded the right to vote, increasing the political power to be tapped by the next movement. The sugar lobby was right: abolition of the slave trade was indeed followed by emancipation and ever-expanding human rights.

Climate activists take heart! Abolitionists met the great moral challenge of their time, and we can meet ours. They made slavery a moral anathema 200 years ago, and we can make carbon pollution morally abhorrent today. If they collected 400,000 signatures with quill pens and parchment, surely we can get 10 million with the Internet. Although they were politically weak, they had moral power and thus prevailed over powerful economic interests. We, too, can win with moral action, and our movement can bring unimagined benefits to every living being.

- Gelien Matthews, Caribbean Slave Revolts and the British Abolition Movement (2006)

- Eric Metaxas, Amazing Grace (2007)

- Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan 2008, http://www.sdnbd.org/moef.pdf (Last viewed March 14, 2013)

- J. R. Oldfield, Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery: The Mobilization of Public Opinion Against the Slave Trade, 1787-1807 (Routledge 1998) (1995)

- David Beck Ryden, West Indian Slavery and British Abolition 1783-1807 (2009)

- Alice Thomas and Renata Rendón, Confronting Climate Displacement: Learning from Pakistan’s Floods (2010)

- http://www.populstat.info. Last visited March 6, 2013

A great article, but I am surprised to see that Marcia did not read “Bury the Chains” by Adam Hoschschild. This book tracks the issues that Marcia covers but gives great prominence to the Quakers who were the leaders behind the scenes. If I remember correctly, nine of the thirteen original members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade were Quakers. Since Quakers could not work publicly because of their Quaker principles, they hired Thomas Clarkson to be their organizer. The abolitionists of the slave trade could not meet in Anglican churches so they mostly met in Friends meetings and it was Friends who were responsible for much of that large number of people signing petitions and as printers produced much of the abolitionist literature. Since this is a Friends publication, I am sorry that this was left out. Perhaps another article on how the British Quakers did their organizing against the slave trade could show us how Quakers should be organizing today against climate change.

The fact that slavery persists to this day in the form of the prison industrial complex, does not give me hope. That the POTUS was unable to address the problem of police brutality and the wreched circumstances of poor and Black people in Amerikkka, does not give me hope. The fact that major multinational corporations and banks are allowed to bend the American economy and political process to their benefit at the expense of the health of our entire planet and the least of her citizens, does not give me hope. Nice try, though.