Testimony in Practice

Quakers seeking to live out the peace testimony grew into a community practicing an evolving commitment to stewardship in the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve in Costa Rica. For the first U.S. Friends who immigrated to the country in 1950, stewardship meant clearing and managing the land to keep it productive for dairy farming. In the decades following, Quakers grew more attuned to the importance of conserving the forest through interacting with biologists conducting research in the area.

One former Monteverde resident recalled how Wilford “Wolf” Guindon, one of the original Quaker immigrants, revised his view of stewardship to embrace forest preservation.

“He went from a man who sold chainsaws to a man who protected the forest,” said Harriet McCurdy, who came to Monteverde in the early 1970s for graduate research in biology.

Guindon, Howard Rockwell, Marvin Rockwell, and Leonard Rockwell spent more than a year in prison for refusing to register for the draft, as required by the Selective Service Act of 1948. These four Quakers were part of Fairhope (Ala.) Meeting of Ohio Yearly Meeting (Conservative); they were drawn to coastal Alabama because of the warm climate and progressive tax system. The sentencing judge told them to leave the United States if they did not want to follow the country’s laws. So they, along with a few dozen other Quakers from Fairhope, immigrated to Costa Rica in 1950 and 1951. Costa Rica had abolished its army after the country’s 1948 civil war.

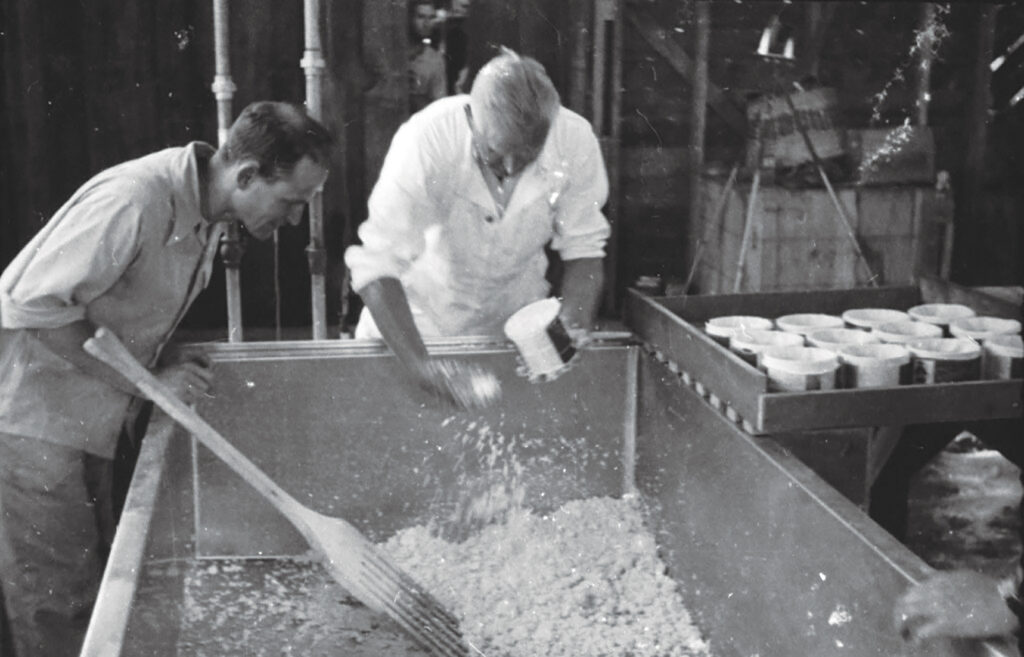

The immigrants spent $50,000 to purchase 3,500 acres of land, some of which they used as a dairy farm to supply ingredients for their cheese factory.

In 1951, the Quakers who immigrated to the area set aside a portion of the cloud forest containing springs and a river that they used for irrigation and hydroelectric power, according to Ricardo Guindon, son of Wilford Guindon. Research biologists later made the immigrant community aware of the variety of species living in the forest, particularly golden toads and endemic, unique species of birds.

Guindon’s father came to see the forest as more valuable standing than cut down.

“It was a whole change in focus,” said Ricardo Guindon.

In San Jose, Costa Rica, a nonprofit group of people with forestry degrees set up the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve. Covering more than 26,000 hectares (around 64,000 acres), it is the largest piece of protected land in the country; 40 percent of the preserve is cloud forest. The preserve was established in 1972 by the Tropical Science Center and Quakers, according to the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve website.

The effort drew support from a group of children in Sweden; young people from England and Germany also got involved. The youths and children raised millions of dollars and created the largest private reserve in Latin America, according to Richard LaVal, a biologist who moved to Monteverde in 1973 and established a bat jungle to educate visitors about the creatures.

Twenty-three thousand hectares of protected area was called the “Children’s Eternal Rainforest.” International environmental groups such as the Nature Conservancy, the World Wildlife Fund, and the National Audubon Society contributed funds to the preserve, according to Harriet McCurdy, who joined Monteverde Meeting and taught at Monteverde Friends School. Protecting the forest became a shared goal of both Costa Ricans and expats. The initial conservation effort inspired the Costa Rican government to set up national parks throughout the country, according to LaVal.

Friends and non-Friends founded the Monteverde Institute, which was born out of their commitment to stewardship, according to Ran Smith, a Quaker hotel owner who has lived in Monteverde since 2004. Smith worked for Friends Publishing Corporation from 2019 to 2021. Reforestation efforts stemmed from people’s desire to take care of the land. Monteverde was started by a Spirit-driven decision, love of nature, and commitment to the stewardship testimony.

“What they’re seeing is that testimony in practice,” said Smith.

Quaker spirituality, commitment to education, and forest stewardship intertwine in Monteverde. Monteverde Meeting began with a core group of traditionalist Quakers, members of the Conservative branch of Friends. The congregation rests on a solid foundation of Quaker values, language, and decision making, according to Smith who lives on the farm of one of the community’s founders. Neither the meetinghouse nor the neighboring Friends school has a parking lot because Friends seek to discourage driving-related development and pollution.

The founding group had children and formed a long-standing community. Subsequent waves of immigration in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s brought additional residents. The meeting community is in transition as the founders age; many are now in their 90s. When Monteverde Friends School is in session, the number of attenders at meeting for worship increases. That meeting includes around 14 children and a small group of active members. Attenders typically stay for a year or two while members make longer commitments. Smith is 53 years old and is one of the youngest members of the meeting.

Living in Monteverde and seeing Friends’ commitment to the stewardship testimony has led some non-Quakers to embrace the faith. McCurdy was not a Quaker when she and her then-husband, George Powell, came to Monteverde for graduate research in biology. She had graduated from Earlham College and was familiar with Quakerism. McCurdy and Powell became friends with Wilford Guindon and his wife, Lucky. In the early 1970s, McCurdy joined Monteverde Meeting.

After discontinuing the graduate research in zoology that had brought her to Costa Rica, McCurdy used her master’s in education to teach classes at Monteverde Friends School. At that time, the school had 24 students; it now has more than 100. When she taught there, almost the whole student body consisted of children of expats, with three or four Costa Rican pupils.

When biologist K. Greg Murray and his wife moved to Monteverde in the 1980s to do their dissertation research on seed dispersal by birds, he had not previously heard of Quakerism. He had a spiritually based respect for nature. He initially attended the meeting as a way of getting to know the residents of his geographically remote new home.

“You became integrated into the community by going to Quaker meeting,” Murray said.

When Murray and his wife immigrated, the Monteverde community did not have television, and there were only five cars on the whole mountain. To get to the Monteverde Preserve, visitors had to take a “dusty, slow bus ride” on a “rickety old bus,” Murray said.

The couple lived in Monteverde from 1981 to 1983. Even after leaving, Murray kept his connection to Monteverde by purchasing property there and building a house, which he rents to tenants when he and his family are not using it. Murray and his wife took their children out of school one month early each year to travel from the United States and stay the summer in Monteverde.

Left: Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve. Photo courtaesy of Laura Melvin.

Right: Emerald toucanets perching and eating on a branch in Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica. Photo by jibz.

Monteverde Meeting grew with the addition of international Quaker retirees as well as Costa Ricans who were attracted to the community by the quality of education offered by Monteverde Friends School, according to Richard LaVal.

LaVal is a bat specialist and a former member of the board of directors at the Monteverde Institute, which hosts students from the United States who come to visit and study. LaVal is 85 years old and worships at Monteverde Meeting. Asked for his reflections on how the stewardship testimony influenced Quaker conservationists in the area, he said the Cloud Forest Preserve would not have existed without Quaker efforts. LaVal does not reflect on Quaker philosophy as much as he demonstrates his faith through action to care for the earth. He did field work and took students on research trips in Monteverde for 40 years before an ankle injury prevented him from continuing.

“Certainly Quakers are environmentalists,” LaVal said.

The stewardship testimony not only underpins the work of Quaker biologists but also of Friends in the Monteverde hospitality industry. Monteverde’s world-famous beauty made it inevitable that visitors would come, according to Smith. Smith saw himself as an ambassador for ecologically sound tourism. Most of the full-time residents of Monteverde are in the tourism industry and care about the forest. Local Quakers reinforce those values, according to Smith.

Monteverde Friends Meeting and School. Photo by Michael J. West.

Such tourism forms the backbone of Monteverde’s contemporary economy.

“Ecotourism is now the driving economic force, not dairy farming,” said forest ecologist Robert Lawton, who joined Monteverde Meeting around 1980.

Smith believes that businesses should benefit the communities in which they are located as well as the environment. He draws on Quaker principles and Friends’ history when making business decisions. His faith leads him to approach business matters with humility and a willingness to listen.

Tourism declined dramatically because of the COVID-19 pandemic. On April 1, 2020, Costa Rica shut down to stem the spread of the virus. Most businesses closed. Smith stayed open and continued to pay his 22 staff members their full salaries during the shutdown. It was 20 months before international travelers returned to his hotel. He was forced to either restructure his debt or sell. He told God that he was willing to let go of the business, if needed. Out of the blue, some investors agreed to purchase the business.

There has been nearly no recent development in Monteverde. In 20 years, there has not been a single new hotel constructed, according to Smith. The local government strictly limits permits to run water lines and install streetlights.

The stewardship testimony has not changed, but it is being tested more than ever, according to Smith. In the last ten years, the testing has become more intense as financial pressure to develop has increased.

“There is a lot of pressure, mostly dealing with money, that is hard to resist,” Smith said.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.