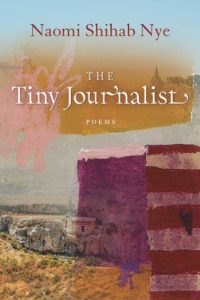

The Tiny Journalist

Reviewed by Michael S. Glaser

November 1, 2019

By Naomi Shihab Nye. BOA Editions, Ltd., 2019. 128 pages. $24/hardcover; $17/paperback; $9.99/eBook.

By Naomi Shihab Nye. BOA Editions, Ltd., 2019. 128 pages. $24/hardcover; $17/paperback; $9.99/eBook.

Naomi Shihab Nye’s The Tiny Journalist is the most heart-grabbing and transformative book my comfortable and privileged American eyes have read since Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me.

Nye’s “tiny journalist” is her imagined construction of a voice prompted by the Facebook postings of a young Palestinian girl. Through that voice and the recalled experiences of her refugee Palestinian father and his family, Nye writes about human suffering and the hunger for justice in a place we call the Holy Land.

They came at night with weapons.

What was our crime? That we liked

respect as they do? That we have pride?

Good art often pushes us to ask uncomfortable questions like, how might the way I have framed my understanding of something limit my ability to see a larger truth hiding behind the truth I think I am seeing? Nye directs us toward such reflection in an “author’s note” when she reminds us: “Since Palestinians are also Semites, being pro-justice / for Palestinians is never an anti-Semitic position, no matter what anybody says.”

The Tiny Journalist challenged my understanding about what is happening in Israel and the occupied territories by opening wide a window to look at the conflict in human rather than political terms. The poems raise awareness of things that human dignity and justice require us to see lest we be embraced by darkness.

Reading these poems overwhelmed me with heartbreak at the brutality occurring. They engaged me in asking how we might better develop our capacities for connection, compassion, and care, as I felt shame at my country’s direct complicity in the pain that is being inflicted on the Palestinian people, and their yearnings for “what could have been, what might be.”

Why don’t they write about us more?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Why don’t they ask the right questions?

In the United States we speed to our vacations on superhighways. In Palestine, human beings try to imagine “the luxury of open roads” without gates and soldiers.

Do they see the kids who have to walk to school

through the drainage ditch?

Because they won’t let them cross the road?

Tell my story, tell my story.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Does the wide world know there are two roads,

one for them and one for us? And ours isn’t good?

These poems tore at the cloth of my uncritical understandings. In the poem “America Gives Israel Ten Million Dollars a Day,” the imagined voice of the tiny journalist asks if we can imagine her sorrows: the inability to move about without guns pointed at her, and to sleep without fear of soldiers knocking on her door and taking loved ones away. She speaks to her pain of living daily in the shadow of a wall “looming over [our] lives”; of neighbors being “rounded up at gunpoint . . . / brutally beaten . . . / massacred for a rumor of stones”; of villages that are “humming songs of the absent ones”; of being “blamed for everything” by oppressors who have forgotten “what they took, / how they took it.”

How does one not feel the anguish of a Palestinian father who says, “This is normal here . . . / bombs exploding / . . . / tear gas billowing over our streets / . . . / SOS / We are so tired.”

Typical of Nye’s spirit, these poems, rather than being expressions of anger, are devoted to compassion and justice. They aim to remind us that dignity and truth matter.

Her father’s voice (“The Old Journalist”) remembers the old neighborhood, the old days when “We never fought, / could not imagine wars.” And the imagined voice of the tiny journalist thinks “The saddest part? / We all could have had / twice as many friends.”

These poems shed new light for me on ways the United States is complicit in creating a Holy Land in which two peoples suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder seem inexorably trapped in a horrific reality that may serve powerful interests but surely not the people themselves. “Babies say, Mine, mine, but babies are kind.”

With deeply human voices, this book re-framed my understanding of the Palestinian experience. Consider, for example, Nye’s poem called “No Explosions”:

To enjoy

fireworks

you would have

to have lived

a different kind

of life

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.