“Sure!”

“Do it!”

“Go for it!”

When we asked Friends who have served in elective office what advice they would give to a young Quaker interested in politics, these were the answers from former member of British Parliament Tania Mathias, former U.S. Congressman Rush Holt Jr., and current state legislator Wendy Gooditis. Judith Kirton-Darling, who served in the European Parliament, views standing for elective office as a civic responsibility for people with the right temperament and skills. Jo Vallentine, who served in the Australian Senate, calls political office “an amazing opportunity for service.”

Quakers in recent decades have often defined their political role as opposition and protest. They challenge the military, take banks to task, organize for climate justice, and see themselves as speaking truth to power.

We are interested in Friends who are “power,” in the sense of being elected officials who are part of the political system. After being deeply involved with Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL) and having worked in state-level politics in Virginia and Oregon, we think that it is important to understand and appreciate the experience of Quakers who have actively sought and served in elective office. In short, what is it like to be a Quaker in politics?

We have talked with Friends in several counties via Zoom, and we also draw on webinars, interviews, and memoirs. All these political Quakers happen to participate in the unprogrammed tradition, but their political values and goals are not identical. We talked with one member of UK Parliament from the Labour Party and one from the Conservative; both had insightful comments. People came to politics from many routes. One was an important participant in South Africa’s Anti-Apartheid Movement; another was a labor union official; another was a policy wonk and lobbyist; and yet another noticed a local leadership gap and thought, I could do that.

The roles are varied. We draw on the experience of members of school boards; city councils; state legislatures; the British, Scottish, and European parliaments; the Australian Senate; and New Zealand and South African cabinets. The issues and stakes may differ, but we found many commonalities that we want to share.

Quakers in political office start with an advantage: colleagues usually expect that they will be trustworthy. Quaker history can inspire respect even from political opponents, and a powerful and positive reputation may follow them into local arenas. Other officials tend to assume that Quakers must be highly principled, even when they disagree with the policy choices that arise from those principles. Approaching politics from a place of faith opens unexpected doors. For example, FCNL staff report that talking about their own faith background helps to establish common ground with some conservatives about protecting God’s environment, and that the history of Quaker work for peace and disarmament can open conversations.

Time and again, we heard the word “heart.” Bring your heart to the work of politics, advises Jasmine Krotkov, who served in the Montana legislature. Krotkov would remind other lawmakers that their work is about people, not making laws for their own sake. DeAnne Butterfield, an experienced lobbyist who served on the city council of Boulder, Colorado, says Friends should talk about what’s in their heart when visiting with elected officials and remember that Spirit is in the room with them and those they’re trying to persuade: “We are not alone in this work if we pay attention. If we bring our Light, it can illuminate for all.”

Political Quakers can bring openness and transparency to issues marked by rigid partisan and ideological divides. “Always I was searching for neutral language, for open processes,” Marian Hobbs writes about serving in the New Zealand cabinet. “It was the process that was my focus. If the process was trusted, if people’s fears were heard and lessened, then I might be able to lower the conflict.”

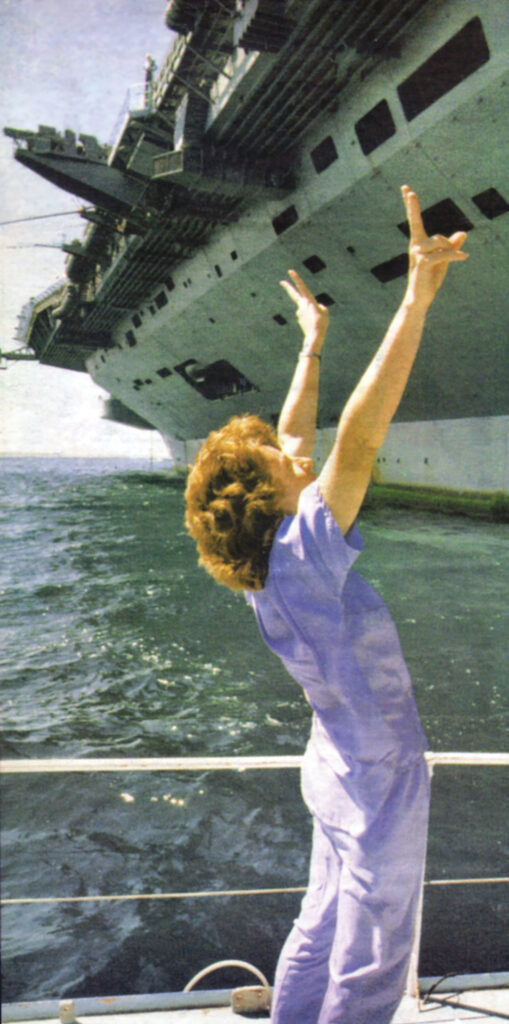

Politicians are accustomed to being harangued by angry constituents and attacked by members of other parties. When Friends respectfully disagree while seeking common ground, other politicians can be taken aback; way sometimes opens. We repeatedly heard that Quakers in politics bring a refreshing voice because they try to listen carefully to everyone and look for the merits in what others say, even those who are on record opposing something of great value to Friends. One Friend noted that colleagues of the opposite party appreciated her evenhandedness as a legislative committee chairperson. Jo Vallentine, who was elected to the Australian Senate to represent the tiny Nuclear Disarmament Party, used social settings to search for shared interests with opposing members, and was sometimes surprised. This self-described “irritant” and gadfly developed a working relationship with a right-of-center colleague around a concern for human rights. Parker Palmer calls this aspect of the Quaker approach to politics the “habit of humility,” which he defines in his 2011 book, Healing the Heart of Democracy:

By humility I mean accepting the fact that my truth is always partial and may not be true at all—so I need to listen with openness and respect, especially to “the other,” as much as I need to speak my own voice with clarity and conviction.

What Quakers have to offer from the outside, such as organizing marches and letter-writing campaigns, can sometimes be similar to other pressure groups. What they have to offer as participants within the political process, however, is vital and even distinct: the willingness to listenactively and search unrelentingly for common ground.

Openness does not mean meekness, of course. Wendy Gooditis is willing to march across the aisle to “scold” a colleague in the Virginia House of Delegates if they have advocated what Gooditis sees as a deeply misguided policy, but she tries to do so with a smile that recognizes the person’s views are sincerely held.

Quaker integrity is the foundation for another important role in the political system. Politicians and diplomats need quiet, neutral settings to talk candidly in ways that are impossible in public settings. FCNL’s office, one block from the Hart Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C., provides a private venue where members of congress and staff can meet to explore common ground without political posturing. It helps that FCNL sustains its nonpartisan reputation through transparency about its own lobbying goals.

The Quaker United Nations Office (QUNO), which operates in both New York City and Geneva, Switzerland, also provides venues for the quiet diplomacy of face-to-face conversations and informal forums: representatives to the UN and its agencies can interact without their briefing books and talking points. Diplomats who would not meet in fully public settings—or at least not productively—will accept QUNO invitations. QUNO’s New York Quaker House is close enough to the UN to be convenient but distant enough to be inconspicuous. Former codirectors Jack Patterson and Lori Heninger have described QUNO New York as a lubricant that facilitates interactions so they do not become overheated. Lunch-time meetings where diplomats balance plates on their knees in a living room are much different from a formal luncheon with place cards. QUNO Geneva also hosts gatherings in other cities when they are the sites of important meetings. Since 2013, it has arranged 20 off-the-record meetings for diplomats to help build trust around UN climate negotiations. Confidential meetings “give people a space to listen,” in the words of former director Jonathan Woolley. QUNO gatherings are “a space to connect and test ideas” without being held to specific positions and “a safe space mentally and physically for people to share.”

QUNO’s role in facilitating international agreements like the Law of the Sea Treaty highlights the role of Quakers as advocates of peace and peacemaking, a role that is often central to their work as well as to the perception of their fellow politicians and the public. Friends in the twenty-first century work on a wide range of issues—just look at FCNL’s dozen or so legislative priorities—but their public “brand” remains peacemaking and peacebuilding.

Marian Hobbs of Aotearoa/New Zealand and Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge from South Africa both came to Quakers and to electoral politics from radical activism. As convinced Friends, they found themselves in national cabinets with responsibilities that allowed them to emphasize peacebuilding over traditional military roles.

Madlala-Routledge discovered Quakers while an anti-apartheid activist in the 1980s and worked to raise up women’s voices in the African National Congress and the National Assembly of South Africa after the political transformation of South Africa. In 1999 she was unexpectedly named deputy minister of defense. In that role she helped to form the African Women’s Peace Table, a platform bringing together women peace activists and women in the military to look at peace through a gender lens. Many in the military assigned to peacekeeping in Congo and Burundi were happy to center reconstruction and “developmental peacekeeping” rather than policing.

Hobbs held cabinet posts in the early 2000s, including minister for the environment, minister of disarmament and arms control, and associate minister of foreign affairs and trade. She shifted the mission of New Zealand’s international aid agency to include a formal policy that “all strategies and programmes consider the risks of conflict and are designed to prevent conflict and build peace.” When New Zealand and Australia sent forces in 2003 to prevent civil war in the Solomon Islands, the agency engaged in active peacebuilding that went beyond military intervention.

These Quaker peacebuilders draw on long heritage. In nineteenth-century Britain, John Bright stood out among members of Parliament for steadfast adherence to the peace testimony. Herbert Hoover, who was the best-known American Quaker from the 1910s to the 1940s, was instrumental in civilian relief work during World War I and was an early supporter of American Friends Service Committee and its post-war relief work. As President from 1929 to 1933, Hoover pushed to extend a naval arms limitation treaty and repudiated the American habit of military intervention in Latin America. British member of Parliament Philip Noel-Baker won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1959 for working tirelessly for nuclear disarmament.

Friends in elected office are challenged to see beyond simple yes/no issue advocacy as well as partisan politics. Successful Quaker policymaking usually requires working within a coalition. We may have clear and persuasive voices, but we are a very small slice of the electorate. Sometimes the alliances are straightforward: such as Quakers in the United States working with Mennonites and Church of the Brethren as the three historic peace churches, or Quakers in Britain working with Methodists and the Salvation Army.

Building a successful coalition may involve compromises that upset those Friends who, at worst, are issue absolutists. Many Quakers get involved with politics because their policy goals have grown out of deep spiritual conviction. Nevertheless, once someone is in office, whether the U.S. Congress or a local council, they cannot remain a single-issue politician. Voting for an imperfect policy may not be a failure of integrity, and the work of building cooperative relationships may be more important than a specific policy outcome. George Gastil, who has served on a southern California school board and city council, comments that it may be better to have a good result with 5–0 vote than a slightly better policy adopted 3–2 but with a dissatisfied minority. Another Friend approaches problems from multiple perspectives, understanding that there is more than one legitimate point of view. Because there is a larger truth, it is acceptable to change one’s mind. “Noticing is a huge skill,” says DeAnne Butterfield about the need to be open to the ideas and views of others.

Friends can bring to political life a deep concern for issues of peace and justice that they share with other activists but also a groundedness in the Spirit, the firm foundation that makes it possible to hear everyone’s story and bring full and loving attention to everyone’s concerns.

British member of Parliament Catherine West addresses a fundamental question in her 2017 Swarthmore Lecture, writing that “alongside other Quaker values such as simplicity and sustainability, actively advancing the cause of equality is both a political imperative and a spiritual vocation.” West addressed a concern that weaves through Quaker history: does the hustle, bustle, and horse-trading of political life undermine and even contradict a full spiritual life? Should Friends maintain the position of virtuous outsiders who point out the mistakes and sins of others without risking the same sins themselves? Not everyone is suited to a life of lobbying, campaigning, and legislative committee rooms. Nevertheless, we agree with her desire to show people who are disillusioned with politics that one of the best responses is to participate as fully as they are able, because “politics is essentially about changing the world around us for the better through dialogue rather than force.”

Individual Friends will continue to argue whether it is better to work within the political process or to apply pressure from the outside. The choice to push from the outside with rallies, vigils, and letters to the press can be especially appealing when one’s own elected representatives seem unlikely to agree with Quaker stands. We suggest that what Quakers have to offer from the outside, such as organizing marches and letter-writing campaigns, can sometimes be similar to other pressure groups. What they have to offer as participants within the political process, however, is vital and even distinct: the willingness to listen actively and search unrelentingly for common ground.

Friends can bring to political life a deep concern for issues of peace and justice that they share with other activists but also a groundedness in the Spirit, the firm foundation that makes it possible to hear everyone’s story and bring full and loving attention to everyone’s concerns. Marian Hobbs urges the importance of finding even the smallest shared ground and seeking out truth in the middle of conflict: in a nutshell, stay grounded in the Spirit to find common ground without giving ground on our basic convictions and vision of a just world.

We need more Quakers in politics. We hope that U.S. meetings and churches will encourage involvement with FCNL advocacy and that Friends will participate directly in campaigns as individuals (for example, our dining room table hosted a convivial envelope stuffing party for a local Quaker mayoral candidate last fall). Meetings can offer clearness and support committees for people who are considering a run for office. Running for office is not for everyone, but if that is the service to which Spirit has called you, we say go for it!

The urging of Friends to get actively involved in their community makes very good sense. Not that they should actively recruit to Friends (not our way) but so that they can bring Friends values to the table.

However, as a retired Headmaster of various prominent independent schools, I know that politicians are only the most visible of public power figures, in fact,R not always the dominant figures. Behind the scenes are numerous “influencers” (to use the modern term), and I know this because I have met many of these influences as a result of their having enrolled their children in my schools.

You absolutely right that influencers who work behind the scenes play an important role in public decisions, sometimes with positive results and often to stifle progressive action. In the early 20th century, prominent Quakers like Rufus Jones, Henry Cadbury, and Elton Trueblood sometimes played the same role, trying to advance a Quaker agenda with figures like Herbert Hoover, but there are few equivalents today. We hope to suggest that being a Friend who engages openly in the political process is a healthier way to bring our values into the public realm.

“Honesty Above All” is missing in modern day political activities. This (Honesty) should be one the Radiant features that all Quakers exhibit in daily activities. I presently have trouble believing many statements made by most present-day politicians. It is my hope that all “Friends” will let their “Light Shine” in all actives. If so, it will eventually be recognized (as a positive asset) by the surrounding observers.

Sincerely,

Charles M. Earnest. Rome, GA(USA)

I’m more interested in “religion” than “god”.

In the words of John Chrysostom (around 400 CE): “A comprehended God is no God”

Religion however simply means “bonding”. How are we bonded to our fellow humans in the community in which we live?

Two things that all religions have in common are:

1) a world view

2) annual festivals that celebrate and inculcate that world view.

It’s one of the reasons I advocate for annual general elections. What better world view is there than the agency that We The People can take in electing our representatives? This needs to be celebrated and inculcated.