Reading Islam’s Holy Book as a Friend

I did not begin my acquaintance with Islam because I was attracted to the religion. Instead, I felt a leading to learn more about Islam because I knew that this faith was misunderstood and often intentionally misrepresented as an enemy. If I were to have chosen a religion outside my own to learn more about, my initial attraction might have been to Buddhism as a community that shares some of my own inclinations toward nonviolence and a contemplative orientation to the inward life. At that time, I did not realize that I could find such qualities among some expressions of Islam. It was not beauty that drew me to learn about Islam. It was a Friendly concern for justice and truth-telling.

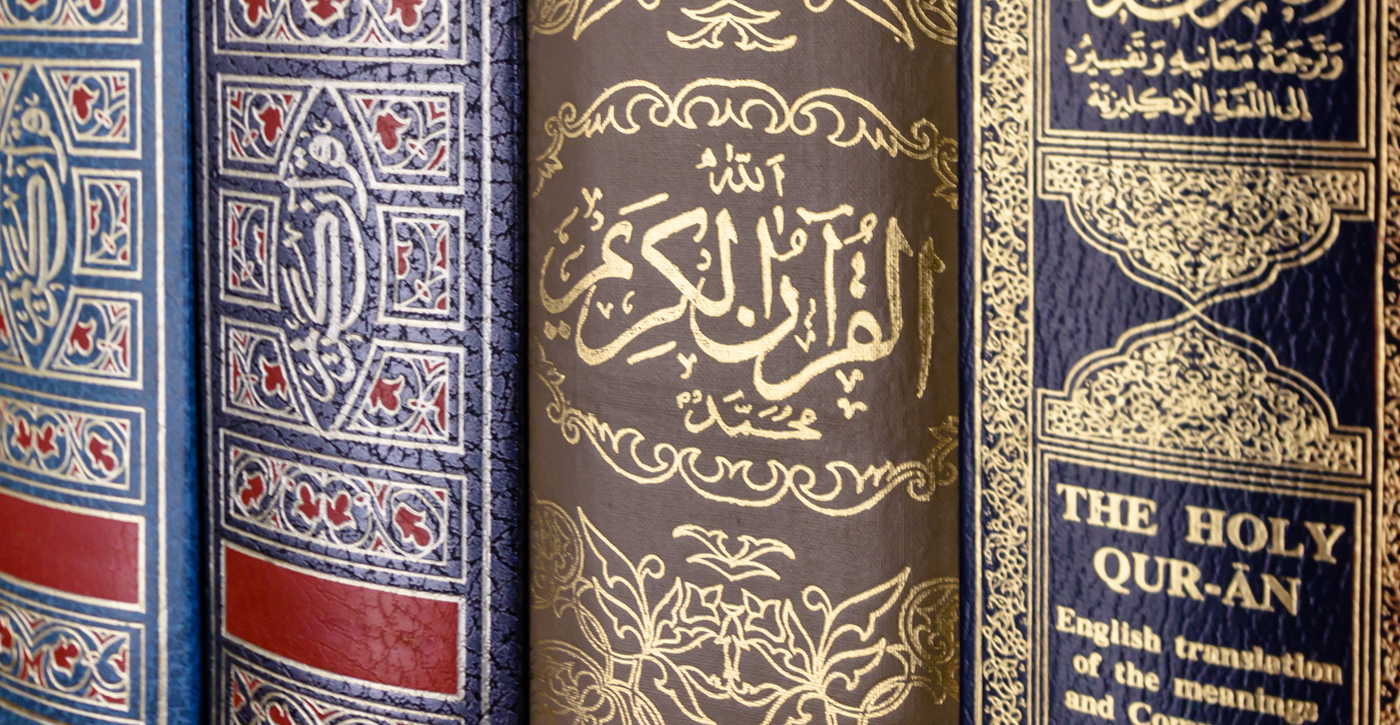

Of the many dimensions of Islam, I chose to focus first on the Qur’an because it is authoritative, greatly loved by all Muslims, complex, and capable of a breadth of interpretations. My interest in Islam led me to become acquainted with many Muslims, who brought their sacred text alive in our conversations and taught me to appreciate their holy book. Through their hospitality, I became a guest of the Qur’an.

To be a guest can be a moving experience: receiving the generosity of the host opens another world. Yet being a guest can be slightly unsettling. The imperfectly known courtesies and expectations of the new setting inspire an attentiveness that can leave one a bit disoriented. There are inherent limitations: being a guest also means not being fully at home, but then that is the point of interfaith encounters.

Crossing the Threshold: Doors of Beauty, Justice, and Mercy

Reading the Qur’an can be challenging to a guest. Reading it sequentially can leave one confused. Its organization is not immediately evident. Where does one start?

One entry for the new guest is the door of beauty. Beauty can evoke wonder. My approach to the Qur’an is shaped by my personal experience of Divine Presence. This encounter with God opens me to a recognition of a kindred experience for Muslims. It prepares me for the possibility of a sense of awe that can transcend the boundaries of my own religious community. I can then perceive the beauty of the Qur’an. Here I think for example of the beloved light verse from Sura 24. (The Qur’an is divided into 114 suras, roughly translated as chapters.)

God is the light

of the heavens and the earth.

This light is like a niche,

in which is a lamp.

The lamp is in a glass,

the glass is as it were a shimmering star,

kindled from a blessed olive tree,

neither of the east nor of the west.

Its oil is glowing,

even though no fire has touched it—

light upon light!

God guides whomever God wills to this light

and sets forth parables for humankind.

And God is the knower of all things.

Islamic tradition is rich in interpretations of this highly symbolic passage. In it, Muslims have discerned reference to God, Muhammad, creation, the human heart and its purification, and celestial realities and mysteries. The poetic beauty of this imagery in this verse is like a magnet for the soul.

Beauty can arouse desire. Mystics in numerous religious traditions speak of an innate human desire for God. The great spiritual poets of Islam describe that desire, such as Rumi, who wrote that God planted a desire within the soul to seek God. I feel that it is possible to recognize that desire across religious boundaries. I sense that desire in the heart of Muslims whom I have come to know. That mutual recognition can create a feeling of kinship, and an eagerness to know what inspires and perhaps even what satisfies the desire of the other.

Desire can blossom into love. Rumi’s mentor Shams described the Qur’an as a love letter from God: God loves us even as we desire God. A lover of God is attracted to being with other lovers of God. Our knowledge of God is incomplete because of our human limits, yet we recognize the contours of love, and we find common ground across boundaries. In a small way, I may begin to read the Qur’an in a manner that shares at least some qualities with a Muslim’s experience.

Sura 97 offers another opportunity for wonder:

In the Name of God the Merciful, the Compassionate

Indeed we sent it down on the night of power—

and what can tell you

what is the night of power?

The night of power is better than a thousand months:

in it, the angels and the spirit descend,

with the permission of their Sovereign,

attending to every task.

Peace it is until the break of dawn.

This sura describes the descent of the Qur’an and the attendant experience of becoming a prophet. It is profoundly numinous, tinged with a deep sense of spiritual presence. One night like this is better than an entire lifetime. It brings peace all through the night, even as it utterly changes the recipient because it is a commissioning with a message.

So that is one quality of the Qur’an. All the goodness of the universe is at hand. It is trustworthy, even as it alters one’s life completely, which is exactly what it did for Muhammad.

Another entry point into the Qur’an for the new guest is the door of justice and concern for the marginalized. Islam’s Scripture calls for justice, for honesty in human dealings, for care for those in need. It proclaims woe to those who profess showy piety but refrain from acts of common kindness. Hearing these proclamations may appeal to a guest of the Qur’an. Understandings of justice vary in time and place. What was a progressive understanding of the role of women in society in the seventh century, when the Qur’an was revealed, may not sound fully so in the twenty-first. Modern Muslim notions of justice are decidedly diverse. Certainly not all Muslims would frame it this way, but some contemporary Muslims hear this ideal of justice as a call to resist racism, sexism, homophobia, and the unjust class system. They regard the Qur’an as the basis for a transformation toward greater equality within the Muslim community.

A third door into the Qur’an is the door of mercy. God is constantly called the Merciful One, and humans are expected to emulate this divine compassion and readiness to forgive in the ways they treat others. In almost every conversation that I have with Muslims about their faith and their Scripture, the theme of mercy has come up. I find myself as deeply moved by this emphasis on mercy as I am by the mystical beauty of other passages in the Qur’an. This invites me to revisit my own tradition, to hear anew how mercy comes alive there. Here I feel that the Qur’an has given me a generous gift.

Obstacles

I readily admit that I struggle with some passages, despite the respect that I hold for Islam’s sacred book. Some of these passages are easily explained by insiders in non-literal ways, but I am a guest and do not feel the freedom afforded to an insider. Here is where being a guest has its limits. I do not get to settle internal disagreements of interpretation. Here is where I need Muslim friends to guide me.

Muslims, when faced with passages that seem to be in tension with the larger message that they find in the Qur’an, have a tradition of “interpreting the few in light of the many.” Muslims have assured me that since the verses that condone violence are an exception to the overriding stress of the Qur’an on mercy, such verses cannot be regarded as the center of Islamic concern. Violent extremists are found within all traditions, including Islam, and there is a robust conversation about this phenomenon within the Muslim community. I have been told that if, while reading the Qur’an, one does not feel the overwhelming sense of the presence of divine mercy and, at the same time, compassion for all creation, then one is not truly reading the Qur’an. As an outsider, I stand with my Muslim friends who give great time and effort to promote peaceful understandings of Islam within the Muslim community. At the same time, I recognize that great harm has been and continues to be done that perpetrators justify by different readings of such texts. As with Scriptures in other traditions, readings that are life-giving contrast with those that are destructive.

Muslims themselves feel an obligation to cultivate an openness as they read their holy book. I have been told that guidance derived from the Qur’an is not so much like coordinates on a map as it is like the astronomical placement of stars; both guide, but the stars move and change with the season.

Promoting Goodness

My desire is to read the Qur’an in such a way that it allows me to be a better Quaker for having the encounter, while at the same time allowing Muslims to be good Muslims. I feel that I know what I mean by being a better Quaker: more open to Divine Presence and guidance, more loving of others, more committed to nonviolence and to a just society. I find that being a guest of the Qur’an inspires me to be a better Friend, even though it is not a pacifist text nor one that speaks frequently and explicitly of love for others. That language of love is a Christian value that I bring to the act of being a guest. The Qur’an, however, does speak of the need to care for others, especially those who are not socially advantaged. My reading of the Qur’an’s concern for others awakens in me a desire to live more fully that kind of love, and this in turn can allow me to be a better Quaker.

The second desire is complicated. As an outsider, I do not get to choose what makes a good Muslim. My experiences among Muslims lead me to believe that for them this goodness would include prayer, fasting, honesty, forgiveness, charity, and care for justice. Many would agree that a good Muslim seeks to live a life characterized by consciousness of God and dedication to the oneness of God. I wish to read the Qur’an in such a way that it supports the efforts of Muslims to find these virtues in their reading of the Qur’an and to structure their lives to live out these qualities.

A Deeper Meeting

With regard to religious differences, if there is a deep place, where we recognize one another, where we more fully know and are known by one another, the only way that I know to get there is to allow each to speak their mother tongue of the soul, to listen generously and humbly, to open the possibility of mutual wonder.

Along the way to a deeper unity, we discover our differences, because it is in the particularities of our own community that we are given the words to describe our deepest truths and aspirations, and each community has a different dialect. It has been my experience that each spiritual community has something in it that makes absolute sense to insiders but seems odd to outsiders. To me, part of the work of seeking understanding across religious boundaries includes acknowledging and listening to those elements that are different. It is in those distinctive qualities that we allow one another to sink into the deepest dimension of the spiritual life, where we may find connections that reach across boundaries.

Here I might share a story. At times I have been invited to join Muslims in prayer. I realize that not all Muslims or Quakers would approve of this, but I discerned that I could accept this generous invitation into shared devotion. In fact, to be honest, I did not technically fulfill all the requirements of Muslim prayer because I do not know all the words in Arabic by heart. At such times, I thought them to myself in English, but I joined in the intimate gestures of praise and submission, feeling the sanctity of motions that were not familiar to me. I was not pretending to be a Muslim, and my hosts understood this. I was receiving the hospitality of the Muslims who invited me to participate, and in their hospitality, I experienced the hospitality of the Divine Host who drew all of us together in a moment of holiness. Reading the Qur’an as an outsider and a guest can be a similar experience.

Maybe I can sum up my experience with the Qur’an like this: at times I have had experiences with the Qur’an that help me to feel closer to God. At other times, the Qur’an helps me to feel closer to my Muslim friends, and they in turn help me to feel closer to God. I am grateful for both.

In the final analysis, is it all the same holy mystery toward which we strive? The fact that it is a mystery, beyond the limits of human utterance, compels me to admit that I cannot be sure that I know. Here I recall an occasion when a Muslim said to me, “I can see your noor,” which is the Arabic word for “light.” Muslim spirituality speaks of an inward noor, which is a manifestation of Divine Presence. As a Quaker, I could hear resonances with my own tradition. His light beheld my light in mutual recognition. My experiences among these generous Muslims give rise to a yearning to continue and deepen the encounter, to perceive the beauty and noor, and to be further transformed.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.