A Quaker Minister Reviews Women Talking

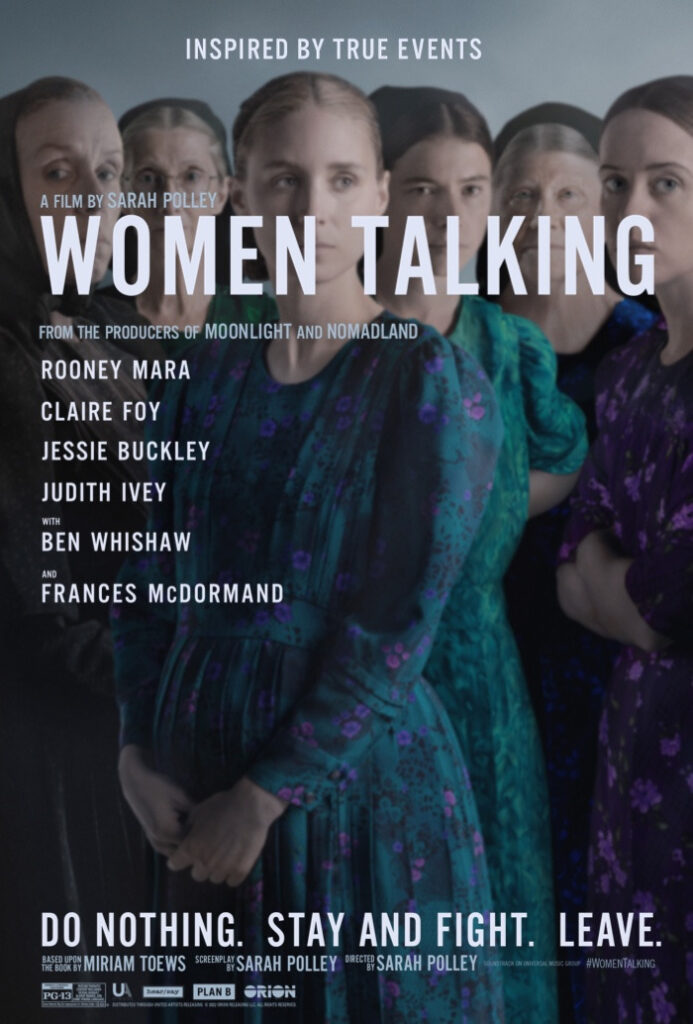

An interview with Windy Cooler is included in our June 2023 podcast.Last month, my friend and colleague Stephanie Krehbiel and I collaborated to publicly watch and explore the themes present in the Academy Award-winning film Women Talking, written and directed by Sarah Polley, who adapted it from Miriam Toews’s novel of the same name. Stephanie is the executive director and cofounder of Into Account, a survivor advocacy organization. We were hosted by the Spiritual Deepening Program of Friends General Conference.

Joined on Zoom by a large and diverse assembly of Friends, we had a conversation that was both broad and deep, with questions about power, peace, and narrative truth. Stephanie, as a former Mennonite who works with survivors of sexual violence in religious communities, is painfully aware that the film and book are not universally well received in the Mennonite communities from which the narrative takes its characters. It is problematic, she says, but we shouldn’t be afraid to address the ways in which it is problematic and how it calls us to pay attention to these dynamics in our own lives, especially around interpersonal violence and corporate discernment.

Women Talking is reminiscent of mid-century plays, rich in dialogue and sparsely contained to only a few sets, but it is also unlike anything produced before it in how it tackles a question that is both alive and hidden in many communities, including Quaker ones: how can one overcome the devastation of interpersonal violence and be made whole again? One character, quoting English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, observes that “little is taught by contest or dispute, everything by sympathy and love.”

The film was inspired by real sexual violence that took place in the late 2000s in a plain Mennonite colony in Bolivia, but as many are quick to point out, that is where reality stops and discrepancies begin in the narrative’s relationship to actual events. In Bolivia, for instance, many men and boys were also assaulted in what are called “the ghost rapes,” and elders’ consideration of how to best address the violence ended with several men being imprisoned. In the film only women and girls are assaulted, and elders do not sanction the imprisonment of those accused. It is also true that, in the real-life events, there are claims from within the same community that the men imprisoned were not the actual perpetrators but scapegoats for others with more social power.

In this regard, Toews admits that the story’s narrative is one of possibility, not experiential truth. Likewise Polley’s Women Talking is not a journalistic film but a work of prophetic vision: it begins with the narrator, a teenage survivor of pervasive sexual violence in this plain Mennonite community, saying that this is a story born out of “wild female imagination.” It is through this imagination that we are invited to ask ourselves what peace will have of us, what forgiveness is made of, what destructive and redemptive power love holds between and among us. In the end it is a thought experiment in what we, any of us, might be together. It is a thought experiment in sympathy and love.

What is imagined in this narrative is a remote group of illiterate women and children seeking to find a way to either live with the men who have assaulted them or to leave their colony and live in a way they cannot imagine. A male school teacher recently returned from excommunication from the colony takes minutes they cannot read. These women and teenage girls, representing three generations, fight and hold onto one another in the hayloft of a barn as they discern what a peace testimony and the Divine will have them do: leave or stay. The dialogue is riveting, challenging, philosophical, and theologically rich, and plays out in the context of a glorious countryside, with sounds of children playing nearby.

Where Quakers might see themselves is in these scenes centered on faith-based discernment and how they capture a strong belief in the rightness of such Spirit-led discernment to face even the greatest evil, a rightness that many Friends assert to be noble and true but that still may fail us. Although the women and children in the film have recently taught themselves what voting is, much as in traditional Quaker practice, they do not vote to determine their future. They must move toward the truth together. They curse and smoke, laugh, insult one another, and in a scene that will forever make me cry, they learn what it means to humble oneself to the harms committed against one another, resist the pull of despair, and choose instead to forge life-affirming connections. This is a model of discernment that I wish we as Quakers could move toward, even if it is not one that exists in the world today, not for Mennonites and not for us.

In the experimental vision of Women Talking, we are invited to consider afresh the real potential of vulnerable, messy corporate discernment, with its truth-telling, solidarity, and faithfulness, to answer the most pressing questions in our communities. While it is true that we have reason to mistrust discernment—that discernment reenacts the power structures of what Quakers call “the world,” and that all too often Quaker processes are abused—we might allow ourselves to be inspired to transform this too with sympathy and love, to emerge from the violence of our world to a place of creativity and prophetic imagination.

I would very much like to see Women Talking but I know it will never appear in the theater here, and I don’t know where it might be streaming, if at all. Is it going to be one of those films that wins applause at film festivals and from critics, but is never available to a wider public? I hope not.

Hi Robin, Women Talking is available online from several services including Google Play, Redbox, YouTube, and Amazon. I hope you get to watch it!