Experimenting with Charismatic Quakerism

Andy Stanton-Henry was featured in the October 2023 Quakers Today podcast.I have a confession to make. Every Easter, you will find me worshiping in a megachurch. I will be standing in a large, modern sanctuary, surrounded by thousands of people. The worship band up front will be leading us in lively singing, complete with an accompanying rock band. The transitions on the stage are impeccable, the technology cutting edge, and the audience multicultural. What’s a good Quaker boy doing in the middle of a charismatic megachurch?

I am there because my parents like to attend the church on holidays, and I want to join them. But I am also there because the worship is a refreshing change of pace from my usual experience in Quaker meetings. It’s good for me to step outside the Quaker bubble from time to time and worship in a less familiar and slightly rowdier setting.

In the spirit of full-disclosure, I’ll let you know that I went through a “charismatic phase” as a teen. I could tell you some wild stories: weeping in worship as Saddam Hussein was executed, learning to prophesy, conducting exorcisms, and speaking in tongues in an old pickup truck. For now, I will just say that, like Quaker worship, charismatic worship is a mix of Divine Presence and human personality, and sometimes visitors have no idea what’s going on. Over the years, I’ve experienced a mix of beautiful and troubling things in charismatic worship environments. Quakerism is my spiritual path, but I still appreciate some things about charismatic worship and wonder if Friends could benefit from some lite (and Light?) experimentation with Pentecostalism.

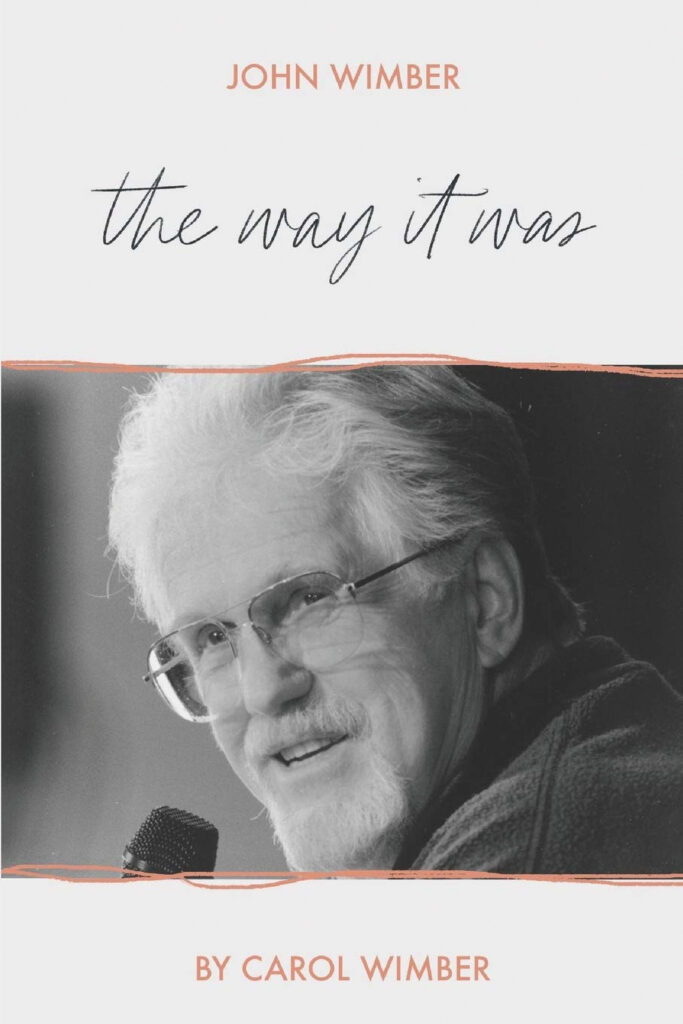

On the surface, charismatic Christians and Quakers couldn’t be more different. But when we dig a little deeper, we are more connected than one might think. In fact, the church I attend on Easter is part of the Vineyard movement, which traces its roots back to Quakers. A founding leader of the movement, John Wimber, was a rock musician in a band that later became the Righteous Brothers. He converted to Christianity through the ministry of an Evangelical Friends church in Yorba Linda, California. This began a period of radical life change for Wimber, who left the band and chain-smoked his way through a Quaker Bible study.

Before long, however, Wimber felt a longing to “do the stuff,” as he put it. He wanted to do the stuff Jesus did in the New Testament—all of it—including all the stuff about healing, deliverance from the demonic, and other miracles. According to Wimber, his pastor told him they didn’t get to “do the stuff”; they only got to read about it, sing about it, and give to it. Wimber exclaimed, “I gave up drugs for this?! When I worked for the devil, he let me do his stuff!”

John stayed a Quaker, however, starting a Bible study and joining the staff. In time, John and his wife, Carol, began having charismatic experiences and felt empowered to do the stuff Jesus did. The church exploded from 200 to 800 people and became the largest church in Quakerism. It underwent a dramatic transformation after a visit from a young hippie named Lonnie Frisbee who concluded his testimony with a statement that awakened the church to a whole new reality: “The church has for years grieved the Holy Spirit, but he’s getting over it! Come, Holy Spirit.” (Frisbee was eventually alienated from the movement due to his controversial methods and sexual identity, tragically dying of complications related to AIDS in 1993. Some argue his role in the Vineyard and Jesus movement has been underappreciated, but his catalytic role is undeniable.)

Eventually, their charismatic worship transgressed the bounds of what a Quaker meeting, even an evangelical one, could support. They met with yearly meeting leaders and “released” their membership. In 1982, John Wimber and a group of like-minded leaders went on to found the Association of Vineyard Churches, which today claims over 2,400 churches in 95 countries. Despite having to leave their home church and denomination, Wimber continued to be influenced by Quakerism. He drew from the casual style of the Friends church; even in their charismatic worship, Vineyard folks adopted a posture called “naturally supernatural.” Wimber embraced simplicity in his lifestyle, avoiding many of the traps that took down other Pentecostal preachers. He also continued the Quaker commitment to peace and nonviolence, and his teachings about “the kingdom” combined spiritual transformation with calls to service and justice.

Their Spirit-led worship was also traced back to Quaker spirituality. Carol Wimber said in an interview that they learned it from the practice of “communion” (or open worship) in which Friends would wait on the Lord in silence and share ministry as they were led. The interviewer noted how Quakerism was more formative for them than people realized. Carol replied: “Oh my, yes. The only difference is we went all the way back to George Fox!” She said they hadn’t read Fox’s journal at that time but found a kindred spirit when they did:

Reading it later, we wondered what our contemporaries were so upset about! A movement of the Spirit happened in our group—for which generations of Quakers had prayed for years, but had no idea how it would look when it came—and when it did happen, it didn’t really fit with Quaker theology at that time.

John and Carol’s daughter-in-law, Christy Wimber (who is now active in Evangelical Friends Church Southwest), also recognized the Quaker connection:

People often think the Vineyard Movement came from . . . Calvary Chapel, when in fact, we are Quakers at the root of who we are; and Vineyard roots are Quaker roots. We have a high value for our Quaker heritage and are very grateful for all God taught us through the amazing Quaker family.

The Wimbers recognized their Quaker heritage with gratitude, despite the complicated way that relationship ended. Christy Wimber told the story of the Wimber family being invited as honored guests to Yorba Linda Friends Church’s 100th anniversary. After the service, a number of older individuals from the church came up to the family and asked forgiveness for their role in pushing them out. Tears were shed and relationships were restored. Christy described it as one of the most powerful experiences of her ministry life.

I don’t mean going back to seventeenth-century religious debates or practices. But maybe our charismatic siblings could help us recover the spirit of early Friends. Maybe we need a little of their spirit in our day.

In the spirit of ecumenicism, I wonder if we can return the favor. Is there anything Quakers can learn from our charismatic siblings in the faith, particularly those in the Vineyard? After all, a query from many of our books of Faith and Practice asks us: “Are you open to new light, from whatever source it may come?” We are also advised to “live adventurously” in our tradition that celebrates “holy experiments” and “knowing experimentally.” Interestingly, John Wimber saw the early Vineyard movement as a kind of “laboratory” for the wider church, experimenting with different methods and practices that might renew the church and change lives.

Maybe they can help us go “all the way back to George Fox” and reclaim some parts of our own movement that we have left behind. I don’t mean going back to seventeenth-century religious debates or practices. Some things are better left behind; both the Vineyard and Quaker movements have ironed out some of the excesses that manifested in their early days. But maybe our charismatic siblings could help us recover the spirit of early Friends. Maybe we need a little of their spirit in our day.

I submit three experiments in charismatic Quakerism for your contextualization and consideration.

The first is simple: experiment with welcoming the whole Holy Spirit. John and Carol Wimber avoided the Pentecostal theatrics of many traveling evangelists and healers. They were influenced by the Quaker advice to avoid “creaturely activities.” If manifestations of Spirit were authentic, they wouldn’t need to be manipulated or manufactured. Instead, Wimber’s trademark was a simple prayer: “Come, Holy Spirit.” He often spoke the prayer after a few moments of silence, with his eyes open, and with a gentle smile. It was part of the “naturally supernatural” vibe that became central to Vineyard culture.

Charismatic Quaker experiments may feel more natural to some Quakers than others. But Quakerism is a Spirit-centric tradition. We are all charismatic in the sense of being ordered and energized by divine graces or gifts of Spirit. (The Greek word is charismata.) Most Quakers are comfortable with some manifestations of Spirit that disquiet other people of faith: extended silence, quaking, prophetic ministry, divine guidance, even inspired dreams or visions. But for various reasons, many wouldn’t be as comfortable with other manifestations that John Wimber would call “doing the stuff,” like divine healing, deliverance from the demonic, resting in the Spirit, speaking in tongues, etc.

What if we made it a practice to simply welcome the whole Holy Spirit into our worship? Of course, the Divine is always near and always active. But there is something special about giving our enthusiastic consent to all God’s words and works. Silently or vocally, we can pray “Come, Holy Spirit” to indicate our openness to the full range of experiences and manifestations of Spirit. This experiment is simple but also a little scary. The Spirit “blows where it wills,” to borrow from John’s Gospel, and could just as easily disrupt as comfort.

The second experiment is to practice healing prayer. This one definitely takes us back to Fox’s time. Though it was apparently suppressed for a time, the reconstructed Book of Miracles has given us a fuller picture of Fox’s ministry. As Rufus Jones wrote, Fox was “not only preaching his fresh messages of life and power,” but he was also “a remarkable healer of disease with the undoubted reputation of miracle-worker.” Friends have continued to describe the “power of the Lord over all” and a “rising of power” within worshipers. That type of language was likely a physical and somatic experience as much as an abstract concept. After all, we are a people called Quakers!

From its beginnings, the Vineyard movement gave a special place to healing prayer. Like Fox, they saw it as an expression of divine power that goes hand in hand with Divine Presence. Friend Richard Foster wrote the forward to Wimber’s book Power Healing, expressing appreciation for Wimber’s grounded practice of healing prayer. In contrast to what Foster calls a “big deal” approach to healing, he suggests:

we see divine healing as simply part of the normal life of the people of God. . . . Seen in this light, healing prayer is merely a way of showing love to people in need. Healing—physical and otherwise—is the natural outflow of compassion, God’s and ours.

In addition to the theatrics of “big deal” healing prayer, there are other barriers to this practice. There are ethical issues related to consent, ableism, and the importance of wholeness rather than simply seeking a miracle cure. Nevertheless, in the spirit of Fox, Wimber, and many other spiritual teachers, compassionate ministries of healing flow forth from our worship. This already has many expressions among Quakers. Some practice healing arts like Reiki or therapeutic touch for trauma healing. Others have incorporated the practice of “holding in the Light,” including meetings for worship that give attention to healing. Yet others practice hands-on healing in more traditional Christian forms, or even anoint the sick with oil. These are excellent. And maybe we can experiment more widely with gifts and practices of healing in our meetings. This violent and wounded world needs healing and needs our prayers.

The third experiment in charismatic Quakerism is embracing worship arts. From its beginning, the Vineyard movement was a worship-led (especially worship in song) community. Wimber being a musician surely played a part in this dynamic. But it’s also related to the fact that worship music was the context in which they experienced Divine Presence and power. Music led them into an experience of intimacy with God and immersion in the Spirit. Preaching, healing, and other gifts flowed out of that experience. Music ushered the people into the presence of God, and, as Carol Wimber put it, “Everything happens in the Presence.”

This emphasis on God’s Presence inspired a collection of new music that transformed the face of sacred music. Vineyard worshipers sang to God and in God, not just about God. The God addressed in their songs was not distant and disinterested but personal and intimate. God loves and woos, desiring to be experienced and known. The music is missional as well as mystical, and calls worshipers to mercy and justice.

When we look back to the early Friends, we don’t see a great concern for musical worship. In fact, many Friends have been skeptical of art, to say the least. But Fox also wrote: “Now Friends, who have denied the world’s songs and singing, sing you in the Spirit and with grace, making melody in your hearts to the Lord.” There are many ways to “sing in the Spirit” and Friends do so in diverse ways. Some Friends are folk musicians, writing about social issues and stories from everyday people. Others lead people in Quaker-friendly hymns and choruses. And there are also Friends churches who sing original or contemporary worship songs with a rock band.

In my experience, singing together is a powerful uniting experience and a meaningful way to center a group in worship. If we worship a living God of continuing revelation, nothing could be more natural than “singing a new song” through original and communal worship music. So let’s rise up singing.

I hope you don’t get the impression that I’m glamorizing charismatic faith or Vineyard worship. I can recount many troubling stories in such contexts. But I can also share stories of meaningful worship and life-shaping experience. I know many Quakers with similar experiences. And many others seek a vital worship experience among Friends. Maybe some experimentation, or cross-pollination, with our charismatic neighbors could help revitalize our faith and practice, whether or not we truly go “all the way back to George Fox.”

Thank you for this article. Quakerism was a charismatic movement of the Spirit when it began, and it has lost a great deal by becoming so intellectual and spiritually dry. I appreciate learning how “Vineyard roots are Quaker roots.” I pray for a revival of charismatic spiritual power active among Quakers today. The huge challenges we all will face as climate change progresses may cause many to long for a more direct and visceral experience of the Spirit at work among, in, and through us in our time.

Did early Quaker charisims include speaking in tongues. What are the Quaker charisims?

Thanks for the article. Indeed I do find it that George Fox and his contemporaries were more of Charismatic in Spirit which made Quakerism flourish . This spirit is now being witnessed among the Kenyan and Tanzanians Friends.

Some people love music or quiet or both or neither.

Hopefully, we experiment on how to bring the best aspects of all views closer together, even if separate services.

What a wonderfully (some may say frustratingly) complicated world.

Yes! Many leaders in the charismatic/Pentecostal movement speak of similar movements throughout history, and one they often cite is early Quakerism. The pastor of a charismatic church I attended for a while did a book on these movements and he had a whole chapter on Quakers.

The Assembly of God at one time had a peace testimony, and it cited the 1660 Quaker Peace Declaration as part of their history

In modern American Quakerism I’ve run across some charismatic expressions. One of these was in a retreat for alumni of School of the Spirit programs. The Sunday morning turned into a charismatic expression, including even speaking in tongues. Another was a gathering of the Friends of Jesus Fellowship when a Saturday evening prayer gathering turned strongly charismatic, including about a third of the participants speaking in tongues. Some of the folks involved in the Fellowship had charismatic backgrounds.

That gathering led me to decide to find a new place to worship. I was first looking for a charismatic church with a theology I could tolerate, which was a real challenge. I wound up in Dayspring Church, an expression of the Church of the Saviour (which was strongly influenced by Douglas Steere and Elton Trueblood) which does not define itself as charismatic and is much more contemplative than most charismatics, but does have a freedom of the spirit which is unusual.

My last time in a charismatic church, I came out thinking that I couldn’t really hear God’s voice, but could sure feel it! Whereas in Quaker meeting I can hear just fine but sometimes don’t feel as much. As you say, we can all learn from each other.

The difference I see in these two movements is that the Charismatic movement sees itself in the interim period, where the Holy Spirit rules until Christ’s return. The early Quakers felt they were living in Pentecost, Christ had returned and his coming was in the heart.