Some of us probably consider from time to time what we would like our parting words to the world to be. As Stephen Wilson Jr., a relatively young Quaker of Green Plain Meeting in Clark County, Ohio, lay dying in 1837, his thoughts were about Friends. He told those around him: “The Discipline of the Society I consider the best written code of laws which could be framed for the government of the true Christian.”

Friend Stephen’s devotion to the Discipline was unusual even for committed Friends of his era. But his vocabulary and sentiments tell us much about the place that books of Faith and Practice traditionally occupied in the lives of Friends. These books of Discipline were, in fact, a “written code of laws.” They were intended for the government of both individuals and the Society of Friends as a group. Their roles and uses have changed greatly among Friends since 1837, but these origins are still apparent in most books today.

The first generation of Friends took for granted that being part of a religious group entailed responsibility and subordination of the individual to the larger group. That was true for almost every spiritual movement in England in the seventeenth century, save the amorphous Ranters. One of the consistent criticisms that Puritans, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Friends had of the established Church of England was that it was not rigorous enough in its discipline and expectations of members—that it tolerated sin instead of advancing holiness. Moreover, having repudiated other church structures, Friends soon realized that they needed consistent procedures that reflected their collective judgments about what God’s expectations for them were.

Perhaps the earliest, and certainly one of the best-known, collection of such judgments was the “Advices of the Elders of Balby,” the fruits of a conference of “Public Friends” in Yorkshire in 1656. The advices included expectations of both meetings—that they should keep records of births and deaths and follow certain procedures for marriages—and individuals—that husbands and wives “dwell together according to knowledge”; that Friends “labour in the thing that is good”; and, my favorite, “that none be busybodies in other’s matters.” With the establishment of the system of monthly, quarterly, and yearly meetings, Quakerism became effectively institutionalized, which led to more judgments about proper behavior and procedure.

By the 1670s, the yearly meeting was generally accepted by Friends as the highest authority, its judgments binding on quarterly and monthly meetings “about the managing of the public affairs of Friends throughout the nation.” These judgments were usually labeled “advices,” but to Friends at the time, deference and obedience to adhere to them were not discretionary—to disregard the advice of one’s Friends was an offense in itself. As other yearly meetings were established in Ireland and North America, they tended to take their cues from the yearly meeting in London, reinforced by the regular visits of weighty Friends from the British Isles.

Just how Friends kept track of their judgments, decisions, and advices is not entirely clear. Doubtless in many cases they were simply “what everyone knew.” But by the middle of the eighteenth century, Friends were referring to this body of accumulated wisdom and judgment as The Discipline. Rufus Jones concluded that it was “a thing of slow and almost unconscious growth. Nobody wrote it outright. No individual or even committee ‘made’ it. It was the creation of the whole group working together. The Society itself ‘made’ it. It was formed out of the accumulations of meeting decisions.”

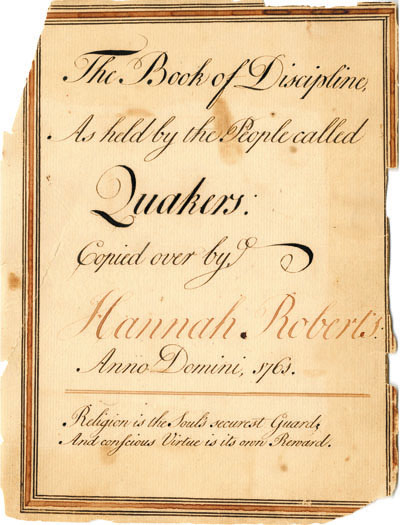

Philadelphia Yearly Meeting made such a collection in 1704. London Yearly Meeting, for once, did not take the lead, waiting until 1738. New England, Baltimore, and Virginia yearly meetings followed suit between 1739 and 1759. The collections, however, were kept in manuscript. Friends who wanted their own copies had to make them by hand. The first printed version, which was of London Yearly Meeting advices, was unofficial, the work of Friend John Fry. Its formidable title was:

An Alphabetical Extract of all the Annual Printed Epistles which have been sent to the several Quarterly Meetings of the People Called Quakers, in England and Elsewhere, from their Yearly Meeting Held in London, for the Promotion of Peace and Love in the Society, and Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, from the Year 1682 to 1762 inclusive . . . containing many excellent exhortations to faithfulness in the several branches of Christian Testimony which God hath given them to bear; and admonitions, occasionally given, for the support of good order and regularity in and among the said people.

Not until 1783 did London Yearly Meeting print a book of Discipline, which it entitled Extracts from the Minutes and Advices of the Yearly Meeting of Friends Held in London. New England Yearly Meeting followed suit in 1785, with Philadelphia Yearly Meeting printing its Discipline in 1797.

Not all Friends were enthusiastic about seeing the Discipline in print. Emmor Kimber (1775–1850), a minister and schoolmaster in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, grumbled that widespread circulation had created a generation of hair-splitting literalists quibbling over the proper construction and interpretation of provisions of the Discipline. “Many have become lawyers, profess to be wise, [and were] so in the letter [that they knew] very little of the crucifying power of the cross of Christ,” he charged.

Before 1827, differences among Disciplines were minimal. As Friends moved west, and new yearly meetings were formed, they continued to use the Discipline of their parent yearly meeting. Indiana Yearly Meeting, for example, was set off from Ohio in 1821, but went on using the Ohio Yearly Meeting Discipline approved in 1819 well into the 1830s. Only with the Hicksite Separation of the 1820s did divergences begin to appear, reflecting the differing judgments of Orthodox and Hicksite Friends about authority and doctrine. While Hicksites averred their devotion to “the salutary discipline of our Society,” they tried to guard against what they perceived as tendencies toward authoritarianism on the part of leading Friends by limiting the terms of elders and members of the yearly meeting executive group, called the Meeting for Sufferings.

Orthodox Friends, in contrast, began to incorporate extended doctrinal sections, laying out what they saw as the important points of Christian belief about the divinity of Christ and the authority of the Scriptures that they saw Friends as sharing with other Protestants. Naturally, books of Discipline were updated to reflect cultural change among Friends after 1860 as old prohibitions such as bans on marriage to non-members and on erecting tombstones were stricken. One of the marks of Conservative Friends was their conservatism about revising the Discipline. Ohio Yearly Meeting (Conservative), for example, did not undertake a major revision of the 1819 Discipline for over a century.

Until the twentieth century, the process for revising the Discipline was relatively simple. Normally, a quarterly meeting would begin the process by sending up a proposal. The yearly meeting would then consider appointing a committee to weigh the proposal. If it did, the committee might make a recommendation before the end of the yearly meeting, or it might recommend holding over the matter for another year. Presumably this practice provided an opportunity for discussion amongst monthly and quarterly meetings, but no such provision was formally built into the process.

In the 1810s, some Friends both in North America and the British Isles suggested the desirability of a Uniform Discipline for all yearly meetings. The proposal for a conference on this subject was one of the forerunners of the Hicksite Separation of the 1820s. Elias Hicks and those who sympathized with him suspected a plot to create a centralized authority that would deprive Friends of spiritual liberty and tend toward creedalism. Those who would become Orthodox Friends were largely supportive of creating a Uniform Discipline. Orthodox Friends raised the question again from time to time from the 1840s into the 1870s.

In 1887, the Gurneyite yearly meetings, which accounted for about 80 percent of the world’s Friends at the time, held a conference in Richmond, Indiana. Delegates from Dublin and London yearly meetings were present, as were sympathetic Friends from Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (Orthodox). The conference is best remembered today for producing the Richmond Declaration of Faith, the definitive statement of Quaker belief for many Evangelical Friends. But equally important was a proposal from William Nicholson, the clerk of Kansas Yearly Meeting. He argued that the tendency of Quakerism in the nineteenth century had been “in the direction of disruption, disintegration, and dissolution.” The solution lay in “unification, compactness, strength, solidity, power of resistance, and an effective wielding of our forces.” And that could be best done, he concluded, by forming a central organization, a triennial conference with legislative powers and final authority over yearly meetings, its scope defined by a Uniform Discipline. For the next 15 years, weighty Gurneyite Friends, most notably Rufus Jones, worked toward that end. They produced a draft Uniform Discipline, and by 1901 all of the Gurneyite yearly meetings except Ohio had embraced it. They thus came together to form the Five Years Meeting of Friends, what is now called Friends United Meeting.

The Gurneyites, who by 1902 were largely pastoral, were not alone in seeing greater uniformity and centralization as a means of building and concentrating the strengths of Friends. The same impulse lay behind the Friends Union for Philanthropic Labor, formed by the Hicksite yearly meetings in the 1870s and 1880s. As the name suggests, the original purpose of the union was for Hicksites to consult and exchange ideas about humanitarian and reform projects, but by the 1890s its biennial conferences included sessions on ministry, education, religious life, First-day schools, and other topics. In 1900, the group became Friends General Conference (FGC). Hicksites disavowed any intention of setting up a central authority above the yearly meetings. However, in the 1920s, the FGC yearly meetings followed the Five Years Meeting model in creating a Uniform Discipline.

The twentieth century saw two significant developments for shared books of Discipline among Friends. One was the understanding of the Discipline as a kind of constitution or fundamental law for a yearly meeting, requiring special processes for change that were different from other acts of a yearly meeting. Before 1900, Disciplines did not specify processes for change, apparently because it was understood that a revision of the Discipline could be handled like any other matter of yearly meeting business. But when the Five Years Meeting established its Uniform Discipline, it referred to it as “the Constitution and Discipline of the American Yearly Meetings of Friends.” Among its provisions was one that specified that “propositions for the amendment of this Constitution and Discipline must be referred to the Permanent Board of the Yearly Meeting, or to a special committee, for its consideration for one year.” If approved, the proposed amendment then went to the Five Years Meeting in session, and if approved there, it was referred to the constituent yearly meetings to take effect once four-fifths had ratified it. When FGC drew up its own Uniform Discipline in the 1920s, it included a variant: proposed revisions originating in the yearly meeting itself, as opposed to a monthly or quarterly meeting, had to be held over for a year. Thus, yearly meetings had the right to act without the consent of FGC or other yearly meetings.

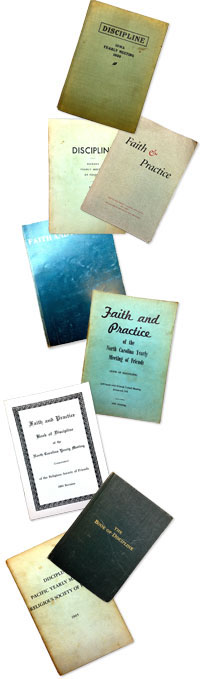

The other change was a gradual shift away from the label “Discipline” to “Faith and Practice.” If this switch was a subject of sustained discussion, I have yet to run across it. The term goes back to William Penn’s book Primitive Christianity Revived in the Faith and Practice of the People Called Quakers, first published in 1696. The first modern use was by English Friend John Stephenson Rowntree for his 1901 book, The Society of Friends: Its Faith and Practice. The first use of the phrase that I have found for what previously would have been a Book of Discipline is by Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (Orthodox) in 1925. New England Yearly Meeting followed in 1930. The Five Years Meeting agreed at its 1940 sessions that the time had come for revisions to the Uniform Discipline, and they set up a study commission. When the commission issued its first preliminary report in 1942, it used “Faith and Practice” for its proposal. The new label was more successful than the draft itself. The increasingly diverse member yearly meetings were unable to agree on the faith portion, and so they decided to return to each yearly meeting creating its own. Most of the constituent yearly meetings moved toward using the title Faith and Practice, although some, such as Iowa, continued to prefer Discipline. And this move was true of FGC and independent yearly meetings as well, although not of all.

In the last half-century, two trends of these books have been clear. One is the observable divergence between the pastoral and unprogrammed yearly meetings. FGC and independent yearly meetings have moved away from including prescriptive statements of faith, instead favoring topical compilations of extracts and quotations on a mass of subjects. The thrust seems to be to highlight a diversity of Quaker voices and viewpoints. In contrast, the more evangelical a yearly meeting, the more likely it is to include prescriptive faith statements and give greater weight to the final authority of the yearly meeting over its members.

The other trend is the long periods of time that revisions of a Faith and Practice absorb. A cynic might say that there is an inverse proportion between the authority of the volumes in the lives of individual Friends and the amount of time needed to draft and approve them. Some yearly meetings now take decades to complete revisions, even as their prescriptions for life and conduct are immeasurably less binding than they were for Friends before 1860. Whether this long-term process reflects Quakerly care and caution or the growing diversity of Friends or perhaps a suspicion of anything suggesting authority, I leave to today’s Friends and their future historians to determine.

[…] Read More about… Quaker News […]