A Vet Confronts a Peace Activist

The summer I graduated from high school in 1955, Pennsylvania was hit by Hurricane Diane. It was the one of the wettest tropical cyclones on record and more than 100 people were killed, mostly by drowning.

My town, Bangor, was lucky. The creek flowing through the center of town drowned cellars and swirled in the streets, but no one was hurt. Towns close to us on the other side of our mountain were devastated.

The call went out for volunteers to help dig out the hardest-hit neighborhoods. At 17, I was proud that my growing body was strong enough to be useful, and my parents were delighted that I wanted to volunteer. After all, they had taught me the Working Class Code, which includes “Do your part.”

I showed up at the town hall at 8:00 on Saturday morning, joining a group of men, some of whom had brought shovels. “You don’t need to use your own shovels unless you want to,” said a man who seemed to be in charge.

He was stocky, wore a tie, and had a cigar firmly planted in his mouth. I didn’t know him, oddly enough—I thought I knew everybody in town—but soon I learned that he was a civil defense official in the region. “I can’t tell you exactly what we’ll do until we get there,” he said, “but I do expect we’ll be back home for supper. Now you’ll just need to sign this form, and then we’ll get in the truck.”

I got out my pen, ready to sign the form but decided to read it first. “I am not now nor have ever been a member of the Communist Party,” it said as best I remember, “nor any organization that plots to overthrow the government of the United States.”

A pit that felt the size of a quarry hole opened in my stomach. I went over to the civil defense official. “I can’t sign this,” I said.

He was visibly startled. “What do you mean?” he asked. “Are you a Communist?”

“No,” I said holding up the form, “but this isn’t right. It’s just . . . not right.”

I felt my face burn with embarrassment. Why was my tongue tied? Why couldn’t I explain what made it so wrong to put a loyalty oath between neighbor helping neighbor?

“Well,” the man said, shifting his cigar from one side of his mouth to the other, “you have to sign it to join us, so suit yourself.” He turned to start herding the others out of the building toward the truck.

I heard their footsteps receding as I read the form again. Eight years before, President Harry S. Truman had initiated the witch hunt that later became identified with Senator Joseph McCarthy. Truman’s executive order was soon met by congressional loyalty investigations, orchestrated to shift public opinion toward the right and generate fear of political attitudes that were associated with the left, like equality, racial and economic justice, and an end to poverty. This was not a simple matter of a bureaucratic form.

At our town’s Presbyterian church, I had caught a debate on the loyalty oath and whether it squared with the larger picture of religious and political freedom in our country. Jesus seemed very intent on the question of our priorities: holding a coin, he asked people to whom they gave their allegiance.

Slowly I put my pen away, returned the form to the table, and slipped out a side door.

My face still burned, and my stomach ached as I trudged home, moving more slowly as I drew closer. Fear-based politics were preventing me from digging mud out of the flooded houses of neighbors! I don’t remember my parents’ reaction, but it would take many years for me to make sense of the pain I felt that day. Loyalty is a positive expression of connection to a group: be it family, community, or nation, or Quaker meeting.

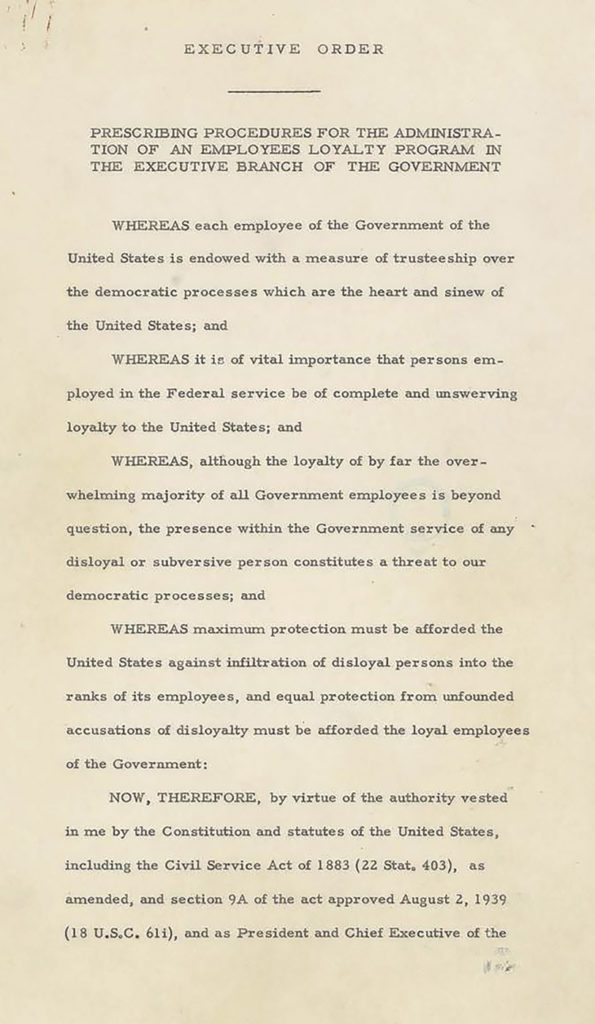

First page of Executive Order 9835, sometimes known as the “Loyalty Order,” signed by President Truman in 1947. Photo www.commons.wikimedia.org.

I found when living in other countries what a deep loyalty I feel to “my people,” the Americans. I stay keenly alert to our leadership’s wielding of that identity to invite us into cruel misdeeds, and have grown almost used to the pain of refusal to go along. Sometimes my choices have a surprising outcome; if we wait long enough, apparent disloyalty may yield an even deeper connection.

In the ’60s, I watched my blue-collar, high school classmates being drafted into the Vietnam War. I was in graduate school and the possessor of a draft deferment. While my draft board knew that I was the kind of conscientious objector who would refuse to join the army even as a noncombatant, and therefore needed to be assigned to some kind of alternative service, the matter was only a technicality as long as I was in graduate school.

As 1963 arrived, I realized that I would turn 26 in November, which was the cut-off point for selective service. All I had to do was stay in school until November—no problem, since I still had years of study left—and the government would set me free of my obligation.

The only trouble was, cruising along at an Ivy League university is not what a working-class person would call “doing my part,” certainly not in comparison with classmates being sent to Vietnam. The break in solidarity was more than I wanted to live with. So I wrote to my draft board with a request that they draft me before my twenty-sixth birthday.

I’d been counseled that there might be some push back from the draft board to my proposal that they place me with the Friends Peace Committee, an agency of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, but the draft board accepted it.

The Friends Peace Committee liked the idea, as I’d already been volunteering with them. The committee straddled some unusual positions, such as advocating both world federalism and unilateral disarmament, carrying out both discrete lobbying and mass media work, mobilizing both older people and young people, and conducting both essay contests and street demonstrations.

“I have a question for your guest,” the man calling in said to the talk show radio host. “Mr. Lakey, how do you get away with dodging your responsibility to go to Vietnam to fight, then getting the government to give you draft credit for protesting the war? That’s outrageous! You are a disgrace to this country!”

This was the fourth radio talk show where a caller launched that attack. How had the right-wing dug this up?

“When Quakers helped found this country, we already believed that war is wrong,” I countered, “and our principles go way beyond the Vietnam War. Peace is patriotic no matter what mistake the government is making at any given moment. Century in and century out, somebody’s got to question the military way.”

The yearly meeting re-doubled our efforts against the war, but as productive as I learned to be, I was never entirely easy with the life I was living. My days, I knew, weren’t anything like those of my classmates in Vietnam.

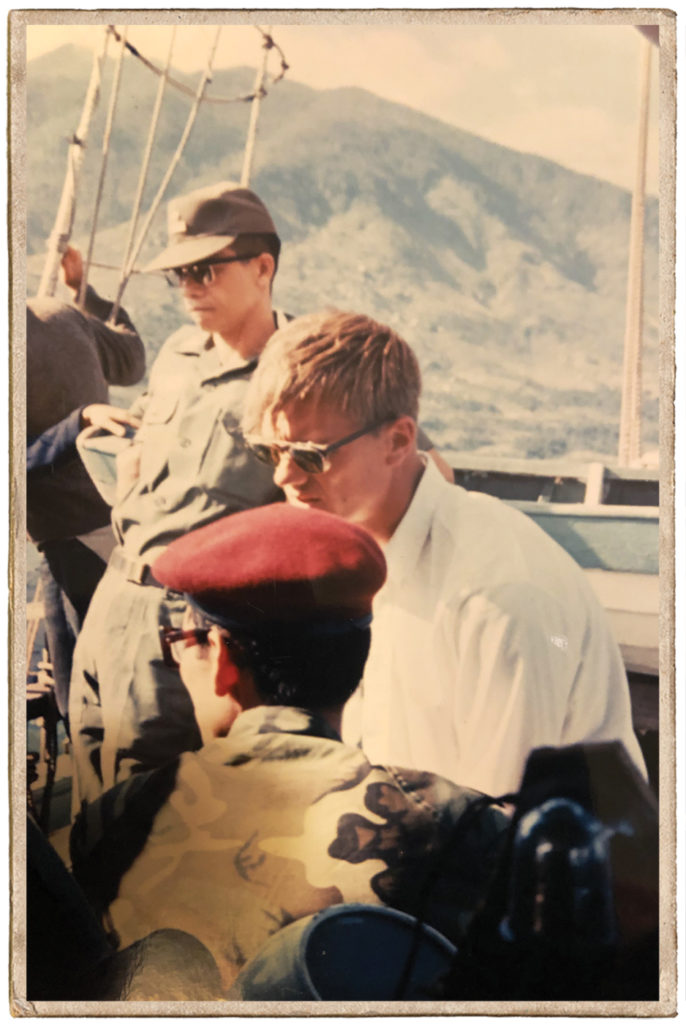

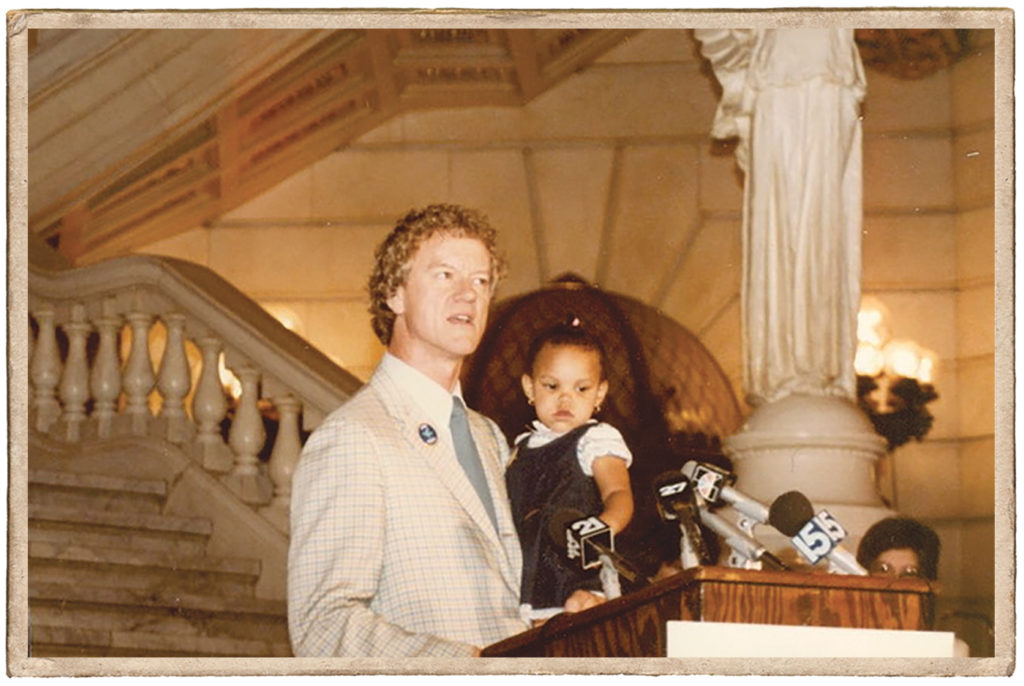

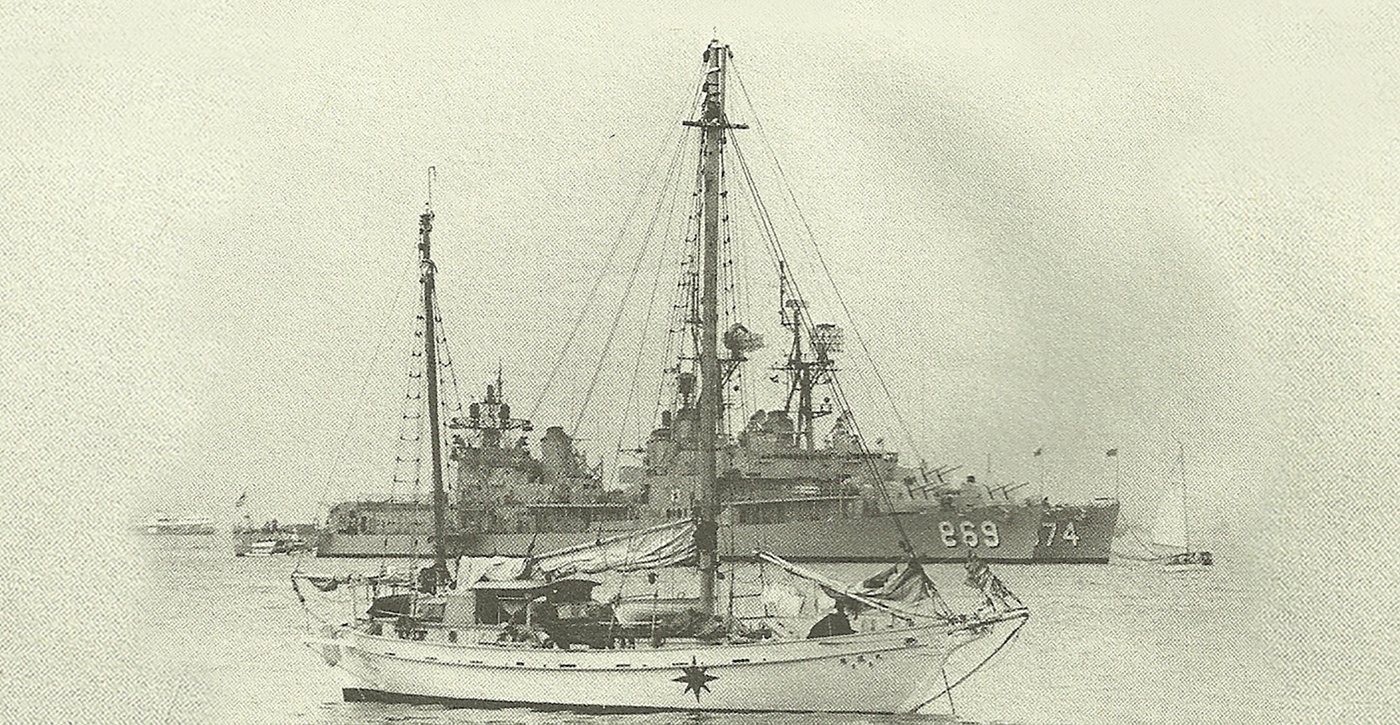

Left: George’s loyalty was also questioned by some when he and other Friends took medical aid to Vietnamese civilians during the war, via the sailing ship Phoenix. Here he is negotiating with officials near the port of Danang. Right: George led Pennsylvania’s Jobs with Peace Campaign in the 1970s. Here he leads a news conference in the state capitol on children’s need for peace, holding his granddaughter Crystal. Photos courtesy of the author.

“George, I gotta talk with you. I’ve been avoiding it.” Richard D’Eduardo stared at me while his body swayed unsteadily. We were in the crush around the bar, and he’d obviously been there for a while.

It was 1975. My classmates chattered around us; Bangor High School’s class of ’55 met every five years, and we were excited to be together. We were proud of our reputation as an unusually loyal class.

“Sure, Richard,” I said. “We haven’t talked for a while. I’m not sure we really talked last time, you know, at our fifteenth reunion.”

“Richard D.,” as we called him, wasn’t a close friend of mine in high school. We shared the mutual respect and easy affection that was typical of our class. Richard took a step closer and straightened his shoulders, still holding my eyes in a gaze that I couldn’t figure out.

“You knew that I was in ‘Nam,” he said, “and maybe you know it was hell.” He took another swallow. It looked like whiskey, on the rocks.

“I knew,” I said quietly. I hoped it wouldn’t turn physical, not in the middle of all this good cheer.

“Okay, so it was hell, and none of us wanted to be there, but we thought we had to serve our country, right? And I’m one of the lucky ones because I didn’t get shot up. It was hell, George, hell.”

Another swallow. “I’ve got no words for what it was.”

While I was listening, I was subtly moving my feet apart to give me better balance. When he hit me, I wanted to minimize the damage.

“And we’re all there because we’re trying to serve our country, right? It’s our fucking country, George; it’s our flag, and we’re gettin’ shot, and we’re gettin’ booby trapped, and we’re losin’ our limbs and losin’ our minds, George, our fucking minds.”

I know I didn’t need to say anything. Richard was into it now: this thing between us that he had avoided. My high school class was small—maybe 115. We knew each other and had school spirit and class loyalty. Richard wasn’t weaving as much; maybe the intensity of what he’s saying was sobering him up. I know I was plenty focused.

“I’m finally home on furlough and I’m trying to forget everything, and pig out on my mom’s pasta, and get into the pants of every Italian girl who will let me. But I can’t skip the 11 o’clock news, not unless I’m screwing, and even then, I think about it; I think about the news. One night I’m watching it, and they’re showin’ another antiwar demonstration, and I see people getting arrested and loaded into the paddy wagon, and I see you.”

He paused, and his stare got even more intense.

“I see George, my classmate, gettin’ in the fucking paddy wagon. My classmate. And if I’d been there,” he paused again, then lowered his voice, “if I’d been there, I would have killed you.”

I no longer heard or saw the others in the room. Our eyes held each other as though the two of us were so alone that no desert or beach or wilderness could provide as much solitude as now surrounded us. I was ready, and curious, and scared, and also wondering what this loyalty challenge would demand later.

Our stare held, and then Richard’s eyes shifted. He looked at his drink, shook his head, and put the glass on the bar.

“All right,” he said, eyes suddenly wet. “That was then. I’ve been home for a while. Time to think. I can hardly do much else, but I do hold down a job. Now I figure I know what you were doing when you got arrested.”

He paused again, then continued. “You were on our side. You wanted me home.”

I slowly exhaled, and found my eyes were wet, too. I had to ask: “And the rightness of the war?”

“Sure, I figured out it was bullshit. Didn’t everybody? But that’s not the main thing, not between us. The main thing is that you weren’t stabbing me in the back.”

Richard suddenly looked shy, and very sober. “So I gotta shake your hand, okay?”

I grabbed his outstretched hand ready to make an emotional response of my own, then saw that he was already looking away. He’d done what he could do. I let go of his hand and half-turned away, grateful, wanting to support his dignity. I clapped his shoulder lightly. “You’re a helluva guy, Richard,” I said, “and this is a helluva class.”

He smiled for the first time, reached for his glass, and raised it in a wordless toast.

thank you George Lakey. I was not a Quaker when I was to be drafted. Went to the Language school in Monterey and did a short tour in Vietnam as a linguist/radio op. When I came home, the Army gave me a commission, because of my degree and prior security clearance, etc.

Soon after returning I went to graduate school in Flagstaff, AZ. There I met the Dean Charles Minor and his wife Mary, Quakers who invited me to come and bring my family to Meeting for Worship.

Soon I felt like I was welcome home. Silence and an accepting community did the trick. I have been a Friend ever since.

May I shake your hand for all you did that I should have done.

Peace and Justice

Chien tranh khong lanh manh cho tre con va lai tat ca sinh vien khach.

What a great remembrance of a time gone by, and how to sides see the view in the heat of the moment. And as in many conflicts, ending in war have the tragedies of war questioning what are we fighting for when the war comes to an end.

Patriotism is a strong bond between Country and men and women too. Unfortunately it can overwhelm the senses that allow us to see right and wrong before it is too late. Just wanted to ask Mr. Lakey; was Carl Zeitlow on the Phoenix with you?