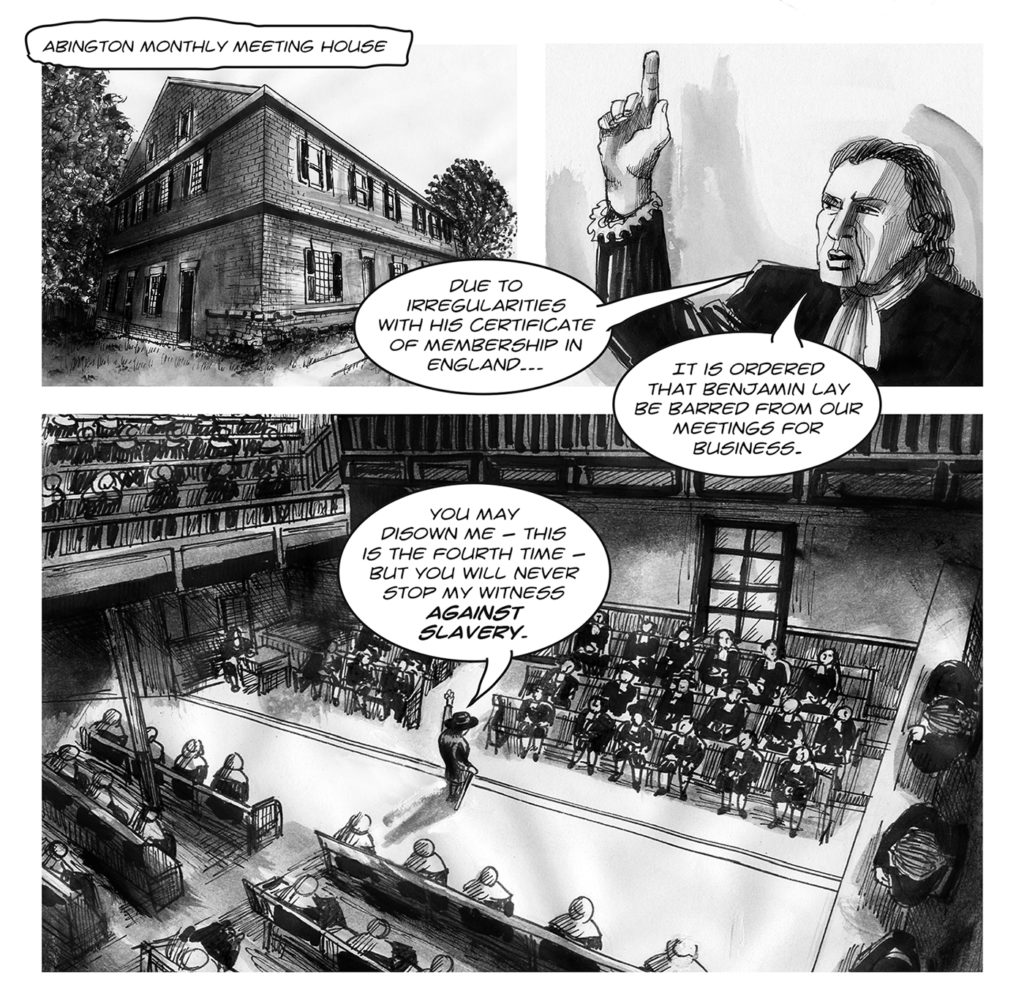

David Lester on Illustrating Benjamin Lay’s Story

Prophet Against Slavery is a new graphic novel that shines light on the life and times of Benjamin Lay, a dedicated Quaker who engaged in radical direct actions to persuade fellow Quakers to become allies in the struggle to end slavery. For 30 years until he died in 1759, Benjamin Lay spoke truth to power and faced discrimination and insults. Prophet Against Slavery was edited by Paul Buhle, illustrated by David Lester, and is based on the 2017 book The Fearless Benjamin Lay by Marcus Rediker.

Previously Lester illustrated 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike and Gruesome Acts of Capitalism. Lester is also guitarist in the bands Mecca Normal and Horde of Two.

John Malkin: History seems static: as if it’s happened, and all we can do is look back at it and observe the linear facts. But it seems obvious that history continues to evolve in the present. Tell me about Benjamin Lay and how you hooked into this book project Prophet Against Slavery.

David Lester: This project began just after I had finished a graphic novel called 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike. It was the story of what we believe to be the longest general strike in history. I completed that 93-page book in 53 days, which is insane! There was a publisher’s deadline, so it had to be done quickly or it wasn’t going to be done at all. I was sort of thinking, I need a break.

Paul Buhle wrote to me. I knew him previously from working with the Graphic History Collective, who did the 1919 book. He wrote to me and said, “We have this book project, and I think you’d be a great artist to do it. It’s on Benjamin Lay.” I had to confess I’d never heard of Benjamin Lay. I know very little about the eighteenth century. (I’m more of a nineteenth-century person.) And I didn’t know that much about Quakers or the history of abolition. I turned the offer down several times.

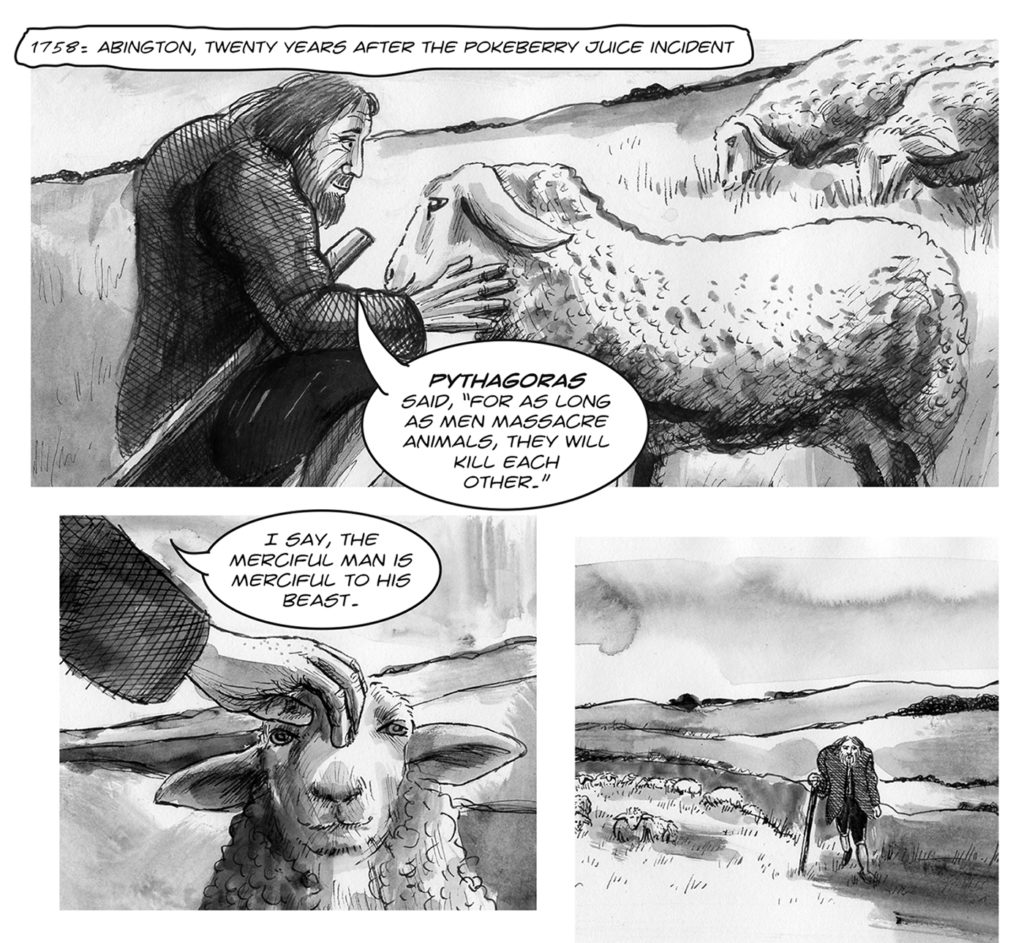

Finally, I read Marcus Rediker’s book The Fearless Benjamin Lay, which is what our graphic novel is based on. And I found Benjamin Lay to be a compelling character. He was a vegetarian and an animal rights activist. He was an environmentalist who warned us that we should, “Beware of men who poison the earth for gain.” That struck me as very contemporary and applicable to our world. He also believed in equality between men and women, and advocated boycotts of products such as tobacco, tea, coffee, and sugar that were produced by enslaved people. Again, he figured out all of this stuff 300 years ago, and today we’re still arguing about whether climate change is real, whether there is systemic racism, and whether America should have a universal healthcare system!

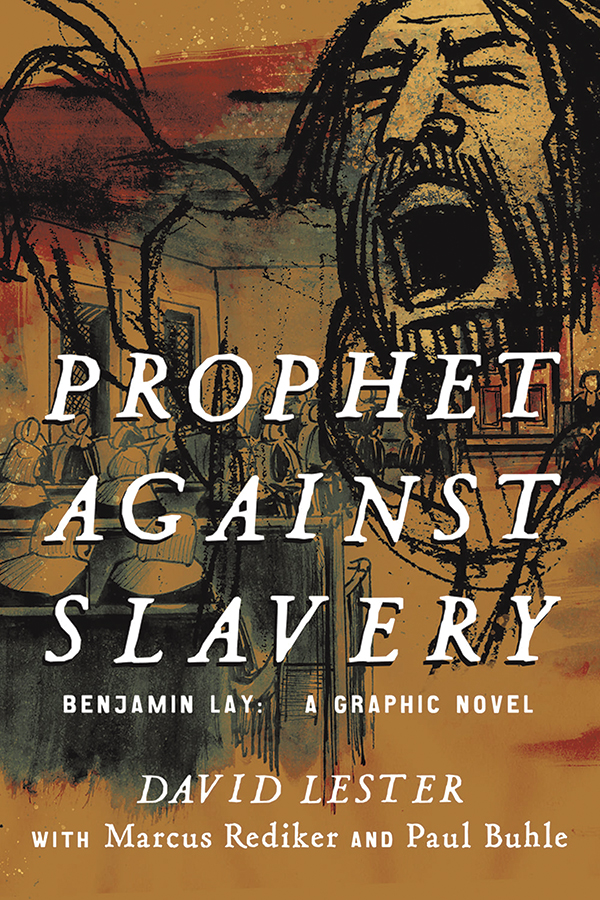

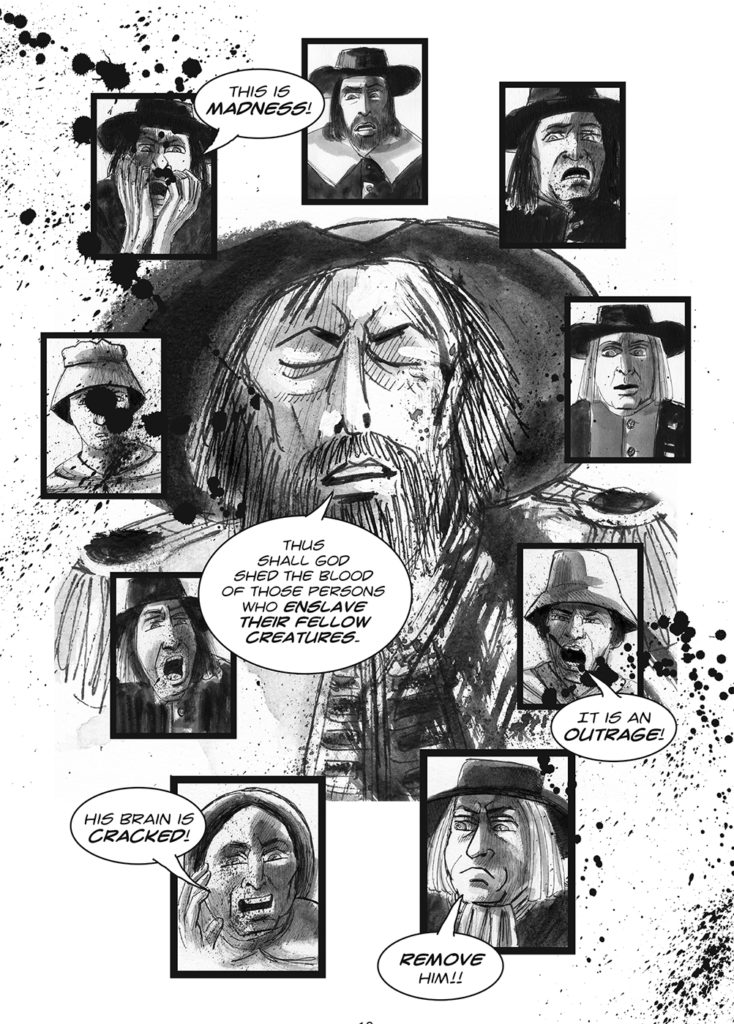

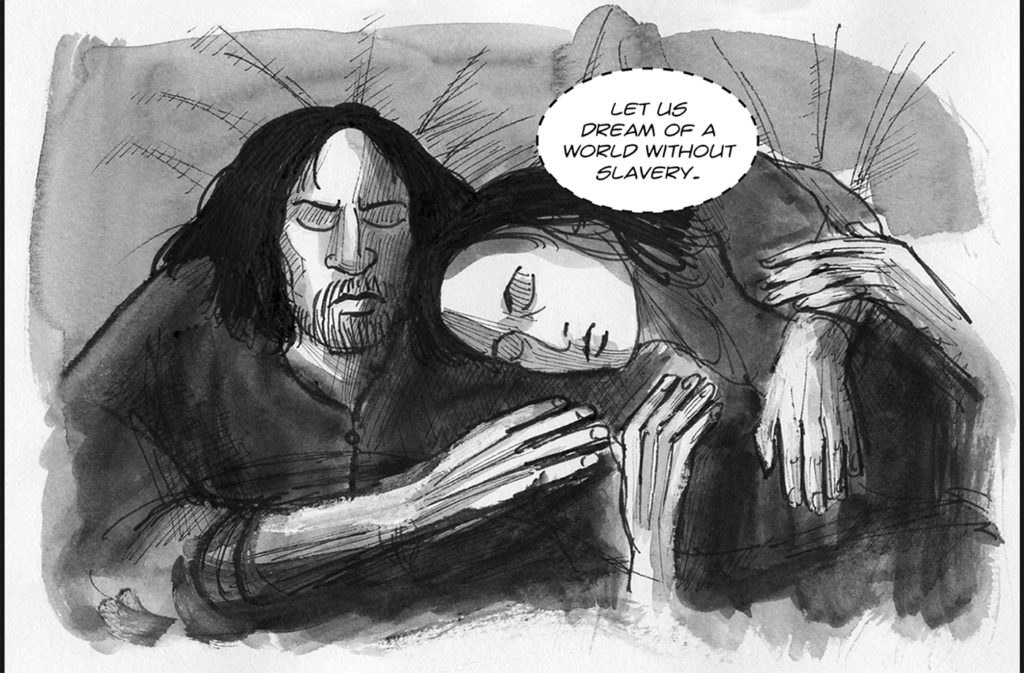

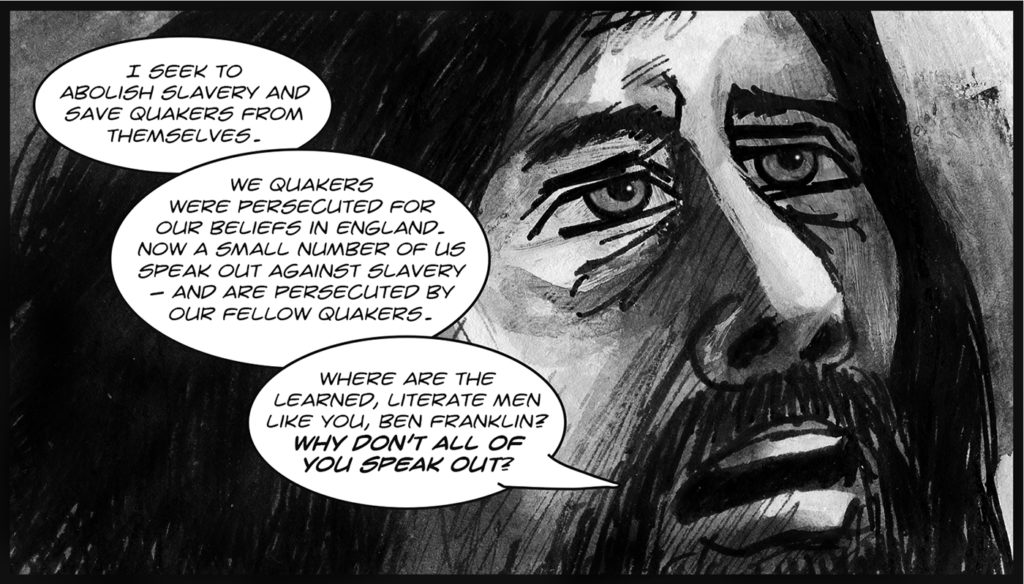

Illustrations by David Lester, excerpted from Prophet Against Slavery (2021).

JM: Tell me about the importance of this story being told as a graphic novel.

DL: It’s one thing to write an academic book that goes in certain places, but if it’s turned into essentially a comic book form, it can reach a wider audience. I’ve discovered that graphic novels are really what people teaching history are using to connect with students, whether it’s in high school or in post-secondary education. This is because students are increasingly unable to read longer texts, like books, so graphic novels are the go-to for connecting with students and getting them interested in history that they might otherwise be intimidated or bored by. Graphic novels are now fundamental for the future of activism and education. Remember, these students will be the future activists and union leaders. I think they need these options.

I ended up writing the script for Prophet Against Slavery in consultation with Paul Buhle and Marcus Rediker. I submitted it to them, and we went back and forth about five times before we got a script that we were happy with. And then I proceeded to draw it.

JM: The Quakers are famous for helping to end slavery in the United States, but 30 years before Quakers embraced abolition, many were still slaveholders. How was Benjamin Lay’s activism based on Quaker ideals?

DL: Quakerism began in the mid-seventeenth century and came out of the ferment of the English Civil War. There were many radical movements, like the Levelers and the Diggers. These were people from the lowest rungs of society trying to create a more equitable world. The early Quakers were very radical, and they would engage in what we would now call “guerrilla theater” to challenge the churches. Benjamin Lay came from a family of Quakers, and that’s where he got his radical ideas on how to approach activism. He was born much later than that original era, but he was aware of that history.

It took a while for him to come to the abolition movement, but Lay was influenced while he was a sailor for 12 years and met sailors who had been formerly enslaved. He realized that as a Quaker he must oppose violence of any kind. And slavery is an act of violence; he was appalled by it and thought that all slavery should be abolished. He was particularly opposed to Quakers being engaged in the slave trade or slaveholding, because it went against the principles of Quakerism. That’s what formed his struggle for at least 30 years until he died.

JM: Lay was a very small person and was described as a hunchback or dwarf. I’m curious if you think that his body size, and being something of an outsider in that way, enhanced his empathy and identification with oppressed people?

DL: We don’t have a lot of information about how he was treated by others because of his size, but there are a few indications, and they are negative. So, he would have had a sense of empathy with oppressed people, and an identification with them. And that goes into his animal rights activism; he didn’t want to mistreat any kind of animal. So he was a vegetarian and made his own clothes because he didn’t want to shear sheep, thinking that would traumatize them. He didn’t ride horses but walked instead, because he didn’t want to use animals as some sort of beasts of burden. He was a very principled person, probably far more principled than most of us are today.

Empathy was a key factor in his activism and his integrity, and his outrage at mistreatment propelled him to go to Quaker meetings and point out who was a slaveholder. That took incredible guts, stamina, and fortitude in a time when most people of European descent considered slavery natural. Imagine trying to fight against that when you’ve been brought up to think that slavery is okay. He had an uphill battle in going into meetings where Quakers tend to be fairly subdued; his outbursts caused great turmoil. He was many times cast out, which is to be disowned from the community because of your actions. He would not stop though.

JM: Describe the guerilla-theater style of direct actions that Lay would engage in.

DL: I start the book with one of his most famous acts of guerrilla theater: one that took place on September 19, 1738. He took a book that he’d hollowed out and loaded with berry juice. He had a sword hidden in his coat and a military jacket underneath his overcoat. He stood up in this Quaker meeting and took the coat off, pulled up the sword, and stabbed it through the book. The red berry juice sprayed at the congregation sitting nearby, so metaphorically, they had the blood of the enslaved on them. Lay was saying they better come to terms with this and eliminate slavery. Of course, he was thrown out bodily. He was thrown out many times and ostracized. One time he was even whipped by a minister for his protests, because of his height and his actions.

JM: There’s a tendency to look back at the abolition of slavery in the United States as being linear and cohesive, but the movement against slavery took decades to evolve and grow.

DL: What emerges in the history is that young people helped to end slavery in the Quaker community. It took decades, and it took having the old guard—the old ministers—die off. Remember at this time in Pennsylvania, Quakers controlled the government. There were government ministers who wrote the laws protecting slaveholders and slave traders. They were totally racist, and they had immense political power. Lay was not only going up against Quakers, he was taking on the government; he was taking on those who had the levers of power. Imagine doing that; you’re just this person who lives in a cave, and you have no resources other than integrity and the moral height of your ideas.

JM: I’m wondering what the current movements to abolish police and prisons can learn from the abolition movement from Benjamin Lay’s time?

DL: I think of this book as being an activist book. It’s about activism, and it’s also meant to propel activism, taking lessons that can be applied to our own activism in the future. Benjamin Lay’s story is pointing activists to the importance of having a long-term view of social revolution. For Benjamin Lay to do what he did for 27 years in a dedicated way until he died is inspiring. He had the integrity, the fortitude, and the stamina needed to work in a situation where he wasn’t certain he’d see results.

I find that I’m drawn to that, and I think it’s a very important lesson we can learn from history and the lives of people who put themselves on the line to make a better world. One of the things that comes out of this book is to not give up and to know that it’s a long, messy road to social progress. In some cases, revolutions occur overnight. But we know that revolutions can backslide and can be full of problems, so you have to be in for the long haul.

JM: This quality of having a long-term view seems very important for social change.

DL: I have another book I’m working on that is about the last year in the life of Emma Goldman, and it brings up the same issues: how did she handle being an activist and an anarchist for 50 years? She came to the end of her life knowing she would never see her ideals realized, as she saw the rise of the Third Reich and the approaching Second World War. It’s all terrible, including the crushing of the Spanish Civil War. How do you remain dedicated? There is a Quaker saying, which I quote at the end of the book: “Let your life speak.” Benjamin Lay is an example, and so is Emma Goldman. They let their lives speak, and that’s what I presented in the book. All I can say to activists is let your life speak by your actions. That’s what Benjamin Lay did.

In many ways, the work I’ve tried to do with Benjamin Lay in Prophet Against Slavery is to give a sense of 300 years ago: a sense of being there, of being a witness to events unfolding. And to do that requires, in part, a sense of gesture and a roughness, so they’re sort of incomplete drawings, which is the effect I wanted. That’s the connection for me between art, politics, music, and the visual arts that I’ve been doing all my life.

The story of Benjamin Lay is important and I wanted to share it with a young teen. I was SO disappointed to find that some of the images in this graphic novel are just too dark, too distrubing. Images can make enduring impressions and I felt they were too upsetting for such a young person. I’m not sure when I would think them okay. I’m going to wait a while and give them Marcus Rediker’s book. I wish we had more contemporary books comparable to Marguerite de Angeli’s Thee Hannah or Kem Sawyer’s Lucretia Mott: Friend of Justice.