After immersing myself in the life of Lucretia Mott over the last several months, I find that she is with me everywhere. On Sunday mornings at worship, I am very aware that she used to sit in the same spacious meeting room. As I welcome guests to my home, I’m conscious of the many more people who came through her own doors. As I mend, I think of all the carpet strips she sewed, and how she decided to keep her needles active on First Day, despite strong Sabbath work taboos. As I plant my peas, I picture her as an old woman, insisting on picking peas in the cool of the early morning, when younger and more nimble fingers could do the work. I feel a sense of affinity with her surprise that people would be moved by the plain things she said.

After immersing myself in the life of Lucretia Mott over the last several months, I find that she is with me everywhere. On Sunday mornings at worship, I am very aware that she used to sit in the same spacious meeting room. As I welcome guests to my home, I’m conscious of the many more people who came through her own doors. As I mend, I think of all the carpet strips she sewed, and how she decided to keep her needles active on First Day, despite strong Sabbath work taboos. As I plant my peas, I picture her as an old woman, insisting on picking peas in the cool of the early morning, when younger and more nimble fingers could do the work. I feel a sense of affinity with her surprise that people would be moved by the plain things she said.

I am amazed by her patience with endless meetings—abolition, women’s rights, peace and nonresistance, free religion—and I wonder if she knit there too, as I do. When I chafe at the limits of our meeting community, I think of her decision, despite ongoing tension with the Quaker hierarchy about her “mixing with the world’s people,” that it was better to stay among Friends than to leave. When I feel discouraged about a group’s apparent inability to move forward, I wonder at her quiet persistence. And when our collective efforts fall so woefully short of what is needed to transform our current systems of injustice, immorality, and domination, I marvel at her assurance that right and truth will prevail.

I’m glad to have her as such a steady companion in my days. And I feel that I’ve come to better understand the forces that shaped her life—how she, a woman born in the 1700s, came to believe that she had the right and power to be an actor in the affairs of the wider world, how she came to be such a passionate advocate for justice.

As I read, soaking up the story of her life, it was these forces that kept capturing my attention. The whaling community of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, where she was born in 1793, was the first. With the men of the households often gone for years at a time, the women had no choice but to step up and do what was needed to keep the family afloat. Lucretia helped her mother run a shop, and was surrounded by hardy and self-reliant Nantucket women who knew their competence and reinforced in each other the strengths and pleasures of sisterhood. Reflecting back, Lucretia says of those women, “They can mingle with men; they are not triflers; they have intelligent subjects of conversation.”

Then there was her schooling. After the family moved to Boston when Lucretia was ten or eleven, her parents chose to put her in a public school. She notes:

It was the custom then to send the children of such families to select schools; but my parents feared that would minister to a feeling of class pride, which they felt was sinful to cultivate in their children. And this I am glad to remember, because it gave me a feeling of sympathy for the patient and struggling poor, which but for this experience I might never have known.

After several years in Boston, she went to the Nine Partners Quaker boarding school in Hudson Valley, New York, an institution that Quaker preacher Elias Hicks helped found and that was dear to his heart. One of the few things she mentions about her education there was the attention that was given to studying the Middle Passage, and how the cruelties of the slave trade were made vivid in her mind. So she was spared an elite education in Boston, then immersed in a form of “guarded Quaker education” that may have shielded its students from some of the evils of the world, but certainly didn’t hesitate to expose them to others. It was also at Nine Partners that she met her future husband James Mott, who features prominently in what is to come.

Lucretia’s Quaker upbringing undoubtedly shaped her in other ways as well. The women’s business meetings offered an ongoing training ground for leadership. The model of bold truth-speaking and action of George Fox, Margaret Fell, and the rest of the Valiant Sixty, though perhaps muted in this quietest period of Quaker history, was there to be found. John Woolman was not long gone, and Hicks, who also spoke out passionately against slavery, was a deeply respected elder in Lucretia’s life. But the elder who may have played the most critical role was a man I hadn’t heard of before, James Mott’s grandfather, another James. His correspondence with the young couple in their early married life surprised me with its depth and resonance. Wishing that everyone could make the acquaintance of this remarkable Quaker grandparent, I quote him at length.

Lucretia’s Quaker upbringing undoubtedly shaped her in other ways as well. The women’s business meetings offered an ongoing training ground for leadership. The model of bold truth-speaking and action of George Fox, Margaret Fell, and the rest of the Valiant Sixty, though perhaps muted in this quietest period of Quaker history, was there to be found. John Woolman was not long gone, and Hicks, who also spoke out passionately against slavery, was a deeply respected elder in Lucretia’s life. But the elder who may have played the most critical role was a man I hadn’t heard of before, James Mott’s grandfather, another James. His correspondence with the young couple in their early married life surprised me with its depth and resonance. Wishing that everyone could make the acquaintance of this remarkable Quaker grandparent, I quote him at length.

In 1812, when she was just 19 and young James almost 24, he wrote to them:

I consider this a critical moment of your lives, my endeared James and Lucretia, just, as it were, setting out in life. How important that you set out right, and with correct views! How needful that the secret, yet intelligent whisperings of the voice that says, “This is the way, walk in it,” be attended to on all occasions! We live in an age of trial and temptation, with many inducements to deviate from perfect rectitude, and many of these are to be found in our own society. But, my precious children, the solicitude of my heart is, that you follow the example of none further than it affords peace and satisfaction to your own minds.

Five years later, he encouraged them “to submit to a way of living which requires only necessary things” despite seeing “such indulgence of imaginary wants, even in those to whom we are looking up for instruction.” In conclusion, his wish:

That this precious couple may never suffer example to sway them from a line of conduct in every respect, which clear impressions on their own minds dictate to be right for them, is, and has oft been, the fervent wish of Their Grandfather.

And in 1818, as they were facing significant difficulties staying afloat financially, Grandfather James advised:

I am far from wishing to point out any particular line of conduct for you: this must be done by the unerring guide in your own bosoms, which will speak with greater and greater clearness, as you yield unreserved obedience thereto. Do not be discouraged, even if it lead you in some respects to do, or to leave undone, things that may seem as trying as parting with a right hand.

Again in 1820:

Peace within will support under much censure from without. I am not about to point out to you this, that, or the other thing that you ought to do or leave undone; but let me say, and say it emphatically, “keep a conscience void of offense.”

His final letter to them before his death in 1823, four years before the great Quaker separation of 1827, ends with these words:

How much better it would be for those who have suffered themselves to get into a spirit of contending about opinions, could they have felt and seen as John Wesley did, when he said, “We may die without the knowledge of many truths, and yet be carried into Abraham’s bosom; but if we die without love, what will knowledge avail?” Well might this great man call opinions “frothy food.” Therefore, dear James and Lucretia, your aged grandparent, who tenderly loves you, greatly desires your firm establishment on religious ground; that you know what is required of you, and be favored with strength to perform it. Stand open to hear and obey the inward calls to duty, but shut your ears to what this, or that, party would whisper into them. Let party business alone, meddle not with it, but endeavor quietly to repose yourselves where safety is. “To your tents, O Israel,”—God is your tent.

I discovered Grandfather James in a book of letters published in 1884 and edited by a granddaughter of James and Lucretia. As I turned each brittle page with care, I wondered what this world would be like if every young couple had such a loving elder, encouraging them toward a life of courageous integrity, saying, “The dearest wish I have for you is to do what you know is right.”

Lucretia’s earliest spoken ministry was a brief heartfelt prayer, perhaps in response to the death of her second-born child. She became recorded as a minister at a young age—in her late 20s—at a time when her world revolved around her large and growing family and her Quaker community. As the children grew older and the family became more financially secure, her horizons widened. She reached out in immigrant and poor communities in Philadelphia. She took an increasing interest in the plight of the local free black community and of those who were still enslaved in the South. Many of us know the trajectory of her story after that—her steady move into the center of the abolitionist movement; her role as a spark and later an elder for the nascent women’s rights movement; and her ultimate stature in the mid-1800s as the nation’s leading female spokesperson for equality in all forms.

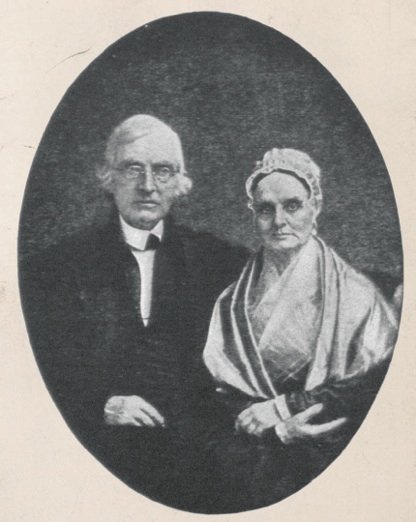

The early forces that launched her on that trajectory have become clear in my mind: Nantucket women, guarded and unguarded education, Quaker tradition, and loving elders. But how did she keep going? Many activists burst on the scene in a flash of brilliance then fade away. Yet Lucretia stayed active, decade after decade after decade—always at the forward edge of the culture, always criticized, always calm, plain-spoken, and hopeful. While there is no single answer, my mind keeps going to her husband James. Barely aware of his existence till I saw a photo of the two of them together in one of the biographies, I now see him steadily at her side.

It was touching to learn how much they loved each other. While away from home, Lucretia wrote to her “beloved one and all,” regretting the absence of a “loved companion.” Following some suggestions to a friend on arranging payments for tracts from a meeting where Lucretia spoke, James concludes with, “so says the best woman I know in this world.” Lucretia later reflects on their life together: “Fourth-day, my dear husband’s birthday,—would that we could pass it together! . . . Forty years that we have loved each other with perfect love.”

What was it like for him to live in her shadow? Was he a meek man, someone without strong opinions, content to follow? Hardly. On their trip together to England in 1840 to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention, he deplored British social conditions, “enabling the few to live in idleness, luxury, and extravagance, at the expense of the many,” and contrasted “the residences of the lords and nobles, their splendid equipage and retinue, with the wretched abodes of thousands.”

He was caustic about the state of Orthodox Quakerism there:

Friends in England, from their habits of industry and economy, have become rich . . . They have received a full share of attention and praise from those who are called the higher classes . . . Pleased with the flattery bestowed on them, they have been gradually sliding from the simple doctrine of obedience to the “light within.”

He was sad that British Friends tried to protect their young people from the American visitors, “fearing the dangerous tendency of our doctrines.”

On the refusal of the English committee that ran the convention to seat the women delegates from the United States—Lucretia included—he noted their alarm at such an innovation, and their fear that the convention might be the subject of ridicule: “such flimsy reasons and excuses.” Clearly James was a man of conviction.

He writes of a journey they took together in 1842:

We left Baltimore and had seventeen meetings in eighteen days . . . traveling three hundred and fifty miles. Our meetings were all well attended, and some of them large; at most, if not all, more or less slaveholders, were present, and heard their “peculiar institution” spoken of plainly, and themselves rebuked for the robbery and wrong they were committing on their fellow-creatures.

Lucretia may have done all the speaking, and gotten all the press coverage, but this was clearly his work too.

In 1848, when they were visiting relatives in central New York State, Lucretia, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others decided it was time to take the plunge and call the first women’s rights convention. They planned the first day for women only, but the news flew, and the crowd that gathered included many men. None of the women were prepared to chair a mixed group; even speaking in a public meeting with men present was still generally considered “promiscuous.” So James stepped into the breach to chair the historic Seneca Falls Convention for women’s rights.

A hint at what an important role he played in Lucretia’s ability to take on courageous public stands can be seen in a letter she wrote about the visit of some British Friends:

How unworthily have the London committee conducted themselves towards the anti-slavery part of Indiana Yearly Meeting. But what better could one expect from such bigots. I felt a wish to call and see them when they were in this city, but my husband did not incline to go with me, and I had not the courage to go alone.

As the novelty of traveling and being in the public eye wore off, “the drives with my well-beloved husband are the most anticipated, and are ever enjoyed.” Lucretia lived almost 13 years after James died, but stopped going to most meetings, and continued to miss him sorely. “Scarcely a day passes that I do not think, of course for the instant only, that I will consult him about this or that.”

It’s easy to love Lucretia, but I’ve also come to love James, that tall quiet man of deep conviction, whose greeting, according to a friend “was like a benediction,” who was confident enough in himself that he could fully and gladly back a woman like Lucretia who was so far ahead of her time.

Our heroes and heroines rarely emerge fully formed, in miraculous fashion, as isolated players on the world stage. Their greatness is made possible by many forces and many influences: models in the home and religious community; teachers; elders like Grandfather James, who are slow to advise but generous in sharing their deepest values; and beloved partners who recognize a gift and put their weight behind it. Each one of us can draw on the strengths of others to live into our full power, and support our loved ones to do the same. May we all be like Lucretia. May we all be like James.

Lovely!