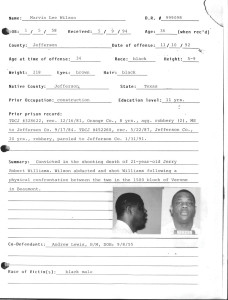

At the 1996 Friends General Conference Gathering in Hamilton, Ontario, Jan Arriens, an English Quaker, gave a plenary talk on his experience corresponding with death row prisoners. A few years before, he had founded an organization called LifeLines that connects people in England to prisoners on death row in the United States. The talk, published that December as a Friends Journal article, “Light on Death Row,” led me to consider writing a death row prisoner. I found that the Church of the Brethren runs a Death Row Support Project so I contacted them, and soon I began corresponding with Demetrius, a man in San Quentin State Prison in California. Then in 2006, I started a second correspondence with Marvin in Texas.

Both of these men had been convicted of murder early in their lives. When I started writing them, Demetrius had just turned 44 and Marvin was 54. Each had spent much of his adult life on death row. Both denied they were guilty of murder and received few visitors. I became friends with these two men and visited each of them twice, four hours each time. (I would have visited Marvin more often, but he wanted to put family on his visiting list hoping they would come.)

On death row since 1994, Marvin was originally scheduled for execution on April 26, 2006, but his execution was postponed when the courts ruled he was mentally retarded. The Marvin I knew was kind and gentle. He loved the Bible and would quote biblical passages in his letters, followed by “Amen.” He made a connection with my handicapped granddaughter, Monet, and would send artwork to her, as well as to Marleigh, her older sister. He complained about the conditions in prison but remained cheerful. He had a beautiful smile. He called my wife “Queen Marian.” I once sent him some facts about the Bible—one being that the longest chapter is Psalm 119. The next time my wife and I visited him, he quoted the entire Psalm to us from memory.

He had diabetes, as did his brother and mother; he learned that his mother had a double leg amputation the same week he was given the new execution date. Marvin asked very little of me. He only once asked for money, and several times requested books he wanted to read.

I am convinced Marvin was innocent of murder. He was deeply remorseful of his drug dealings and robbery for which he was twice convicted. He reasoned that if he had not been dealing drugs, he would not have been arrested for murder. I believe the Marvin I knew was incapable of lying.

In the time since I started writing him, his son, brother, and mother had each visited him once. He was also regularly visited by Drusilla, a woman from Dallas for whom this was a ministry. His visiting list was limited to ten people, and his five execution witnesses all had to be on the list. When a new execution date of August 7, 2012 was announced, he took my wife Marian off the list but kept me.

Shortly thereafter, the letter I feared came: he asked if I would be one of the witnesses at the execution. I knew immediately I could not say no.

Visiting hours for a prisoner are extended on the day before an execution, so I arrived at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit in West Livingston, Texas, at 8:00 am on Monday, August 6. I was surprised that the guards and the woman in charge of the visiting room did not even know Marvin was scheduled to be executed or that he had special visiting privileges.

I was fortunate to be able to visit with Marvin alone for about an hour and a half. No direct contact visits were allowed; we visited through glass while talking on the telephone. Only two visitors were allowed at a time so when his family came, I had to leave and be out of the building before they could be let in. This procedure was repeated the following day, the execution day. I visited Marvin for 30 minutes along with the mother of his son, then left so his sister could come in.

At noon Marvin was transferred to the Huntsville Unit about 45 minutes away. We had to be at the hospitality house, run by a local church, at 3:00 pm for a briefing by the chaplains. They informed us about the process and warned about the media and protesters. We met with some of the protesters while at the hospitality house, including Drusilla, the regular visitor, and Quakers from Dallas.

Shortly before 5:00 pm we were taken to the prison. We walked past the media and protesters, went through security, and waited. We knew we might have to wait several hours for decisions to be made on final appeals. We knew every appeal had been denied when we were informed the execution was about to begin.

Marvin’s five witnesses consisted of his three sisters, his son, and myself. A spiritual advisor, a chaplain, and two guards were also present as we waited quietly, each alone with our own thoughts. Shortly after 6:00 pm, the guards escorted us to the execution chamber.

The room was just large enough for us to stand behind its glass window. Marvin was on the other side, lying down, strapped to a gurney; IV lines ran through a hole in the wall into both of his arms. A chaplain was at his feet holding a pocket-sized New Testament; a warden was at his head. Marvin raised his head and said a few words, including, “I see you, Rich.” I was standing in the back of the room behind the others. He then went to sleep, and soon stopped breathing. A doctor was summoned and he was pronounced dead.

We went back to the hospitality house where Marian was waiting. I hugged her and had a good cry. Marvin’s body was taken to a nearby church, where I touched his skin for the first time. The state of Texas had just executed Marvin Lee Wilson, #999098, the 484th person executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976.

As I reflect on this experience, I am chilled by the ease, efficiency, and routine nature of the state-sanctioned killing of another person. The cooperation of the Christian chaplains particularly disturbs me. John Bright, a nineteenth-century Quaker member of the English Parliament, wrote in 1868:

The real security for human life is to be found in reverence for it. If the law regarded it as inviolable, then the people would begin to also so regard it. A deep reverence for human life is worth more than a thousand executions in the prevention of murder…. The law of capital punishment while pretending to support this reverence, does in fact tend to destroy it.

In his 1996 Gathering talk, Arriens had told us that most prisoner correspondents felt the prisoners gave as much or more than they gave to them. This was my experience. Occasionally death row prisoners become violent, but I am confident that neither Demetrius nor Marvin would have hurt anyone had they been released.

I came home to an envelope with two pictures from Marvin—one for Monet and the other for Marleigh. I am still grieving. I lost a friend. Part of me also died on that gurney that night. I still write Demetrius. His case is under appeal.

[…] corresponding with prisoners on death row. Van Dellen wrote about his experience in an article “Witness to an Execution” that was published in the September 2013 issue of Friends […]

Why did you believe Wilson was innocent?

FACTS OF THE CASE

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, citing the Texas Court of Criminal Appeal’s description of the facts, described the murder of Jerry Williams as follows: On November 4, 1992, Officer Robert Roberts and other police officers entered [Wilson’s] apartment pursuant to a search warrant. Jerry Williams was the confidential informant whose information enabled Roberts to obtain the warrant. Williams entered and left the apartment minutes before the police went in. [Wilson], Vincent Webb, and a juvenile female were present in the apartment. Over 24 grams of cocaine were found, and appellant and Webb were arrested for possession of a controlled substance. Appellant was subsequently released on bond, but Webb remained in jail. Sometime after the incident, [Wilson] told Terry Lewis that someone had “snitched” on [Wilson], that the “snitch” was never going to have the chance to “have someone else busted,” and that appellant “was going to get him.”

On November 9, 1992, several observers saw an incident take place in the parking lot in front of Mike’s Grocery. Vanessa Zeno and Denise Ware were together in the parking lot. Caroline Robinson and her daughter Coretta Robinson were inside the store. Julius Lavergne was outside the store, but came in at some point to relay information to Caroline. The doors to Mike’s Grocery were made of clear glass, and Coretta stood by the door and watched. Zeno, Ware, Coretta, and Lavergne watched the events unfold while Caroline called the police. These witnesses testified consistently although some witnesses noticed details not noticed by others.

In the parking lot, [Wilson] stood over Williams and beat him. [Wilson] asked Williams, “What do you want to be a snitch for? Do you know what we do to a snitch? Do you want to die right here?” In response, Williams begged for his life. Andrew Lewis, Terry’s husband, was pumping gasoline in his car at the time. Williams ran away from [Wilson] and across the street to a field. [Wilson] pursued Williams and caught him. Andrew drove the car to the field. While Williams struggled against them, [Wilson] and Andrew forced Williams into the car. At some point during this incident, either in front of Mike’s Grocery, across the street, or at both places, Andrew participated in hitting Williams and [Wilson] asked Andrew: “Where’s the gun?” [Wilson] told Andrew to get the gun and said that he ([Wilson]) wanted to kill Williams. They drove toward the Mobil refinery. Zeno and Ware drove back to their apartments, which were close by, and when they arrived, they heard what sounded like gunshots from the direction of the Mobil plant.

also review the appellate record:

http://www.clarkprosecutor.org/html/death/US/wilson1302.htm