During the pandemic, there has been a lot of uncertainty, anxiety, and concern for ourselves and for others. Meetings have been canceled, and gatherings and trips have been delayed for months on end. We have been forced to choose our response: do we panic and fall into despair, or do we take this moment to try to create a spiritual sanctuary in our homes? There has certainly been some anxiety in our home, I’ll admit, but over the months we have also found time for self-exploration, spiritual deepening, and worship.

For the past 23 years, I have been a Quaker. I was drawn to the Religious Society of Friends by the opportunity for silent worship with others and by the Quaker valuing of direct experience with the Divine. As Quakers, we open ourselves to spiritual guidance in the form of messages that we may receive for ourselves or for others. We sit in silence, calm our minds, and listen. It’s harder than it looks.

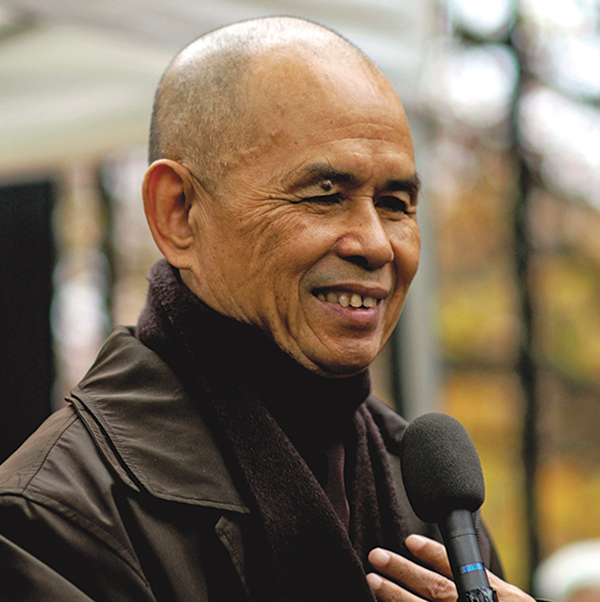

At Richmond (Va.) Meeting, our Adult Spiritual Education Committee organized and led a series of Zoom sessions on eight mystics entitled “Mystics: Living from the Inside Out.” I presented a session on the work of Thich Nhat Hanh, a Buddhist, and Richard Rohr, a Francisan. Both of these men, like the Quakers, have long-standing contemplative practices.

Thich Nhat Hanh in Paris, 2006. Photo by Duc on commons.wikimedia.org.

Since we don’t seem to be able to turn off our brains, perhaps the best we can do is slow the thinking down a bit, so that we are able to experience moments of calm and peace in the spaces between images and thoughts. I have been helped in this process of slowing down, both by my reading of Thich Nhat Hanh’s work on mindfulness meditation and by my own daily practice.

Our meeting’s focus on mysticism has led me—and others I’m sure—to pay better attention to what we experience during silent meditation and worship. Almost every morning, my wife and I sit in silence for 15 to 30 minutes as a part of our daily spiritual practice. Our intent is to quiet our minds and to be open to the experience of oneness. Let me just say again, it’s harder than it looks.

My brain is not a willing companion in this desire to experience oneness. In fact, it seems to have a mind of its own. When I close my eyes, I see a steady stream of images playing on the back of my eyelids: flashes of faces, television characters, a landscape, a house, my parents, an animal, shapes, colors, and on and on. This phenomenon can rightly be called “stream of consciousness,” as it flows endlessly across my field of vision.

In the midst of this stream, it is easy to go off into some tributary of thinking. It’s seldom about the images themselves, rather it’s about some activity I’m planning, COVID-19, a project I’m working on, the aftermath of the U.S. presidential election, or what I’m going to do after sitting in silence.

Whatever it is connects to a whole host of related ideas that then lead to others and others and others. If I’m not careful, I can spend more than a few minutes off in a virtual reality, unaware of the present moment.

It is clear that the human mind is both a gift and a curse. Our minds allow us to think, plan, create, remember, and empathize. That’s the gift. Our minds are also a curse: running like a motor that never stops—even when we ask it to—and generating ideas, pictures, memories, feelings, problems, and emotions.

I know I’m not the only person who experiences the challenge of the wandering mind. It’s written and talked about by contemplatives in all the major world religions. Since we don’t seem to be able to turn off our brains—that constant stream of consciousness—perhaps the best we can do is slow the thinking down a bit, so that we are able to experience moments of calm and peace in the spaces between images and thoughts. I have been helped in this process of slowing down, both by my reading of Thich Nhat Hanh’s work on mindfulness meditation and by my own daily practice.

My mindfulness practice is mostly by way of guided meditations led by Tara Brach (available at tarabrach.com). Her meditations lead me to pay attention to my breath, to the sounds in the room, to the sensations in various parts of my body, and to moments of presence. During the meditations, she acknowledges that the mind may wander into planning, problem solving, and memories. She gently calls me back to presence in the here and now.

Although she makes no explicit mention of the goal of experiencing oneness, it is my own sense that this is what is meant by “presence.”

I have learned when focusing on my breath to say the word “calm” on the in-breath and “ease” on the out-breath. Getting into the rhythm of breathing, relaxing, and saying these words over and over quiets my mind and helps me avoid the habit of focusing on the stream of images and thoughts flowing past me—at least for a little while!

As I practice this “slowing down,” I eventually observe what I’m doing and remind myself that following these thought tributaries is not why I’m sitting in silence. I consciously call myself back to my goal of having a quiet mind and being open to oneness. At the core of my being, there seems to be an inner witness and a still, small voice trying to keep me on track. I am grateful for the help.

Tara Brach presenting her workshop, Widening the Circles of Compassion. Screengrab courtesy of her YouTube channel.

The pandemic has caused many of us to become more contemplative. We have rediscovered the richness of daily spiritual practice in its many forms. We practice being mindful, centered, and open. We nurture what Tara Brach calls that “alert inner stillness.”

The practice of silent waiting on the Spirit in Quaker worship, as with mindfulness meditation, is a method of removing the noise, pushing aside the veil of the ego-self, and settling into a deep silence that makes space for peace and quiet. While Quaker worship leaves open the possibility of receiving messages in this still, quiet space, there is also a deep appreciation for the silence itself and the opportunity for the moments of oneness that it presents.

Many of us have had a few such moments. They are very peaceful and joyful. The experience is of oneness, an absence of duality between the self and something else. When these experiences occur, we observe them with joy. If we slip into a self-congratulatory observation (“I’ve done it! I’m present!”), the moment is gone. The ego-self is easily awakened, I’m sorry to say, and as it re-introduces duality, it takes us away from the stillness.

The pandemic has caused many of us to become more contemplative. We have rediscovered the richness of daily spiritual practice in its many forms. We practice being mindful, centered, and open. We nurture what Tara Brach calls that “alert inner stillness.” We continue to listen to that still, small voice and to observe with the inner witness at the core of our beings. As hard as it is, pandemic or no pandemic, we sit in silence.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.