The first instance of war tax refusal for religious reasons that I have found was in the twelfth century. Saint Hugh of Lincoln (England, 1140–1200) had his religious formation at the famous Grande Chartreuse monastery in France.

When Henry II of England accepted responsibility for the murder of Saint Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, he accepted big penances too. One was to found a Carthusian monastery in Witham. In 1179/80, Saint Hugh (or Hugo, as I prefer to think of him) accepted the invitation to be the monastery’s prior. He stood up for the poor, the sick, and the persecuted Jews. When King Richard (the Lionheart) tried to raise money for the Third Crusade by taxing the church, Hugo—now a bishop as well as head of the monastery—refused to comply. For a while all church property in the diocese (think yearly meeting) was confiscated. Eventually, the king gave in.

It gives me encouragement to know of this story. My own war tax avoidance began in 2000, when I dropped my income below the IRS taxable level. When we take action—big action—on our peace testimony, the first step must be to know ourselves.

In Mountains Beyond Mountains (2003) by Tracy Kidder, Paul Farmer, who provides top-level healthcare to one of the poorest parts of Haiti, comments, “I love WL’s [white liberals], love ’em to death. They’re on our side. . . . But WL’s think all the world’s problems can be fixed without any cost to themselves. We don’t believe that. There’s a lot to be said for sacrifice, remorse, even pity. It’s what separates us from roaches.”

I was definitely a white liberal, but this was before Kidder’s book on Farmer came out. Farmer now speaks my mind. I considered legal versus illegal IRS tax avoidance. I was willing to serve time in prison if need be, but I was not of the personality to accept the possibility that at any moment an IRS representative might knock at my door. That’s why I decided to take the legal route.

Friends of my meeting (Multnomah Meeting in Portland, Ore.) opened their homes to me. I was a vagabond, moving from one place to another, spending several weeks in the summer at United Methodist camps as a volunteer (mostly for kids; I’m a pediatrician). I also spent two- to four-month stints volunteering medical services in Honduras, where I now live. In 2003, the late Friend Alberta Gerould asked me to consider her house to be my home.

It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes a community to support a person of any age making big life changes like these. I had been downsizing since 1992, when I stopped full-time paid work.

I read a lot—mystics of any background were my mainstay. At that time, Eknath Easwaran, an ecumenical Hindu teacher, and Brother Lawrence were my closest friends. I read a lot of coming-of-age novels, very helpful for a person of any age making big life decisions. I had a clearness committee, of course. Now I read a lot of Saint Teresa of Ávila; she’s big on humility, an area in which I have some growing to do.

As a physician, I earned a relatively high hourly wage as a substitute. All of the expenses related to my volunteer work were tax deductible, including my cost of living while volunteering in Honduras. The IRS considers it perfectly reasonable to expend up to 50 percent of taxable income on donations and expenses for volunteer work. I followed the letter of the law (just as any stingy person would). The IRS gave me better spiritual counsel than most Friends would!

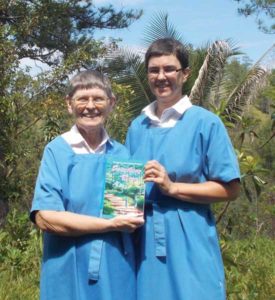

In 2006, I moved to Honduras to found and join Amigas del Señor (Lady Friends of the Lord) Monastery. Before being eligible for perpetual profession (lifelong commitment), I had to reduce my net worth to zero. That was technically difficult after so many years of “prudence.” I actually paid income tax one year to liquidate one retirement plan. For 18 of these 19 years, I have not paid IRS taxes. I am now, at age 71, a perpetually professed Sister. I live on faith, and it feels good.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.