Transformation and Urban Farming in West Philly

When we bought our house in a changing neighborhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the late 1970s, the neighbors said there was no point in trying to plant anything out front. The children in the parochial school who used our street as their playground would just destroy it. The tiny front yards on our street, each maybe four by twelve feet, reflected this fear. All were tidily covered in concrete.

One of my first acts of hope and faith—in the soil and in the children—was to go out with a sledgehammer and pull out all that concrete. To fill in the gaping hole that was left, the handiest soil that came to mind was my mother’s compost pile. So we shoveled it into the trunk of our car and used it to plant a garden.

We started with flowers—which the children didn’t destroy and which brightened the whole block. Over the years, we reclaimed an even smaller bit on the other side of the steps, which is now a combination of early perennial flowers and basil, kale, collards, and colorful red peppers.

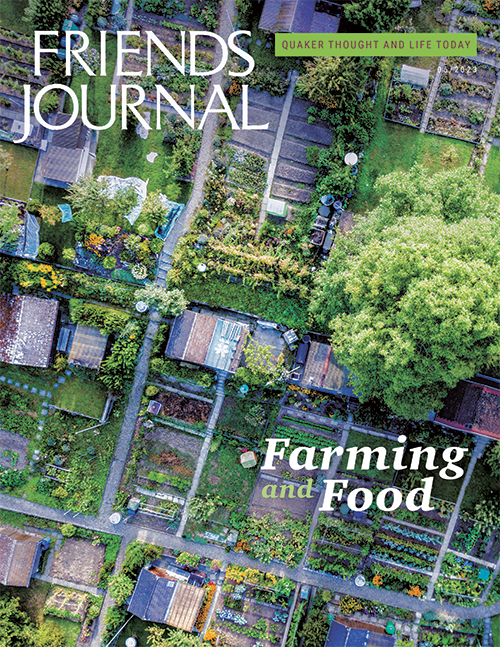

With that experience of transforming an expanse of concrete into a garden, I began to notice other opportunities in the neighborhood. A warehouse around the corner had burned down years earlier, and I joined in with neighbors who were hauling out rubble, bricks, and glass, as the first step in creating a community garden. A woman who was living with us joined this group of hardy guerilla gardeners, found another source of compost, piled it on a cleared space, and began growing vegetables. Gradually the lot was transformed into a more or less orderly collection of 40 or more plots.

As my roots in the community deepened, I found my own place in the community garden: first sharing a plot; then getting one of my own; then putting time into the composting system and the big, front flower bed. It was a pleasure to gradually get to know the other gardeners. There were the old men from the South who brought their farming experience with them, and whose advice was much in demand. There were the immigrants who were looking for a place to grow familiar foods they couldn’t easily find in the stores. I learned that the Africans in the plot next to mine grew sweet potatoes for their greens. Then there were all the other neighbors who had been drawn in by a common love of the soil.

Every fall for years, we held a harvest festival to raise money to pay off our mortgage, till the last payment was finally made and our title to the land was secure. Being able to grow healthy food in the middle of the city was enormously satisfying, but even more compelling were the opportunities it opened up for sharing.

In a neighborhood that was easy to think of as other, I now feel a deep point of connection. My world feels safer; my extended family has been extended and enriched; and it all started with sharing an abundance of tomato seedlings and a love for the earth.

Our garden is part of a City Harvest program started by a local horticultural group. They built a network of connections that linked the local prison with gardens around the city and little food pantries in need of fresh fruits and vegetables. An old greenhouse at Graterford Prison, a focus of so much urban despair, was brought back to life. Men there, with hands perhaps unused to nurturing, put seeds in tiny pots and tended sprouts and fresh, new growth. Then they said goodbye to healthy seedlings, with regret perhaps, and sent them out into the world, where neighbors in city garden plots could plant them in good earth and tend them as they grew.

The man who first worked our garden’s City Harvest plot—another Quaker—was finding unexpected joy in growing this food to give away. I remember finding him working there one Saturday morning and hoping for an extra hand. I gladly left my own little plot to help him harvest kale, collards, and broccoli. When I put them in the tub and gently pushed the great leaves down into the water, they shimmered with silver lights. It was a beauty that astonished. I felt part of a mystery, a sacramental task.

I contributed a bouquet of flowers from the front garden. Perhaps they would find a place on the altar of the storefront church that would receive our harvest. I knew all that good food would be greeted with delight and given out to those in need. I felt part of one great sacrament, starting with those seeds in gentle hands at Graterford.

During this time, I also learned about the Philadelphia Orchard Project. Growing from one neighbor’s dream of planting fruit trees throughout the city, there are now over 65 little orchards around the city that are cared for and enjoyed by the community.

I heard that these little food forests needed native perennial flowers as well. Since dozens of baby black-eyed Susans appear in my garden every year, I began potting them up—in little recycled plastic pots filled with my good compost—and taking them over to my neighbor’s side alley. I’ve dropped off hundreds over the years, maybe a thousand by now, and I love imagining all those black-eyed Susans brightening lives all over the city while providing sustenance for the bees that pollinate the fruit trees.

I began adding fruit to our big, front flower garden—cherry, peach, and fig trees, currant bushes, and hardy kiwi vines. Now passersby not only have a vista of color, but can sample all those fruits in season. Working in that public-facing bed, once rubble, I was primed to notice other efforts at such transformation and was moved to help.

Hearing about the dream of some local youth to create a garden in a smaller lot not far away, I was attracted as if to a magnet and came one day to help them work. The ground was stony, bare, and unpromising. We scraped away and rock piles grew. Two young men sweated beside me, pulling out iron rods, concrete, and more rock. Could this poor place yield anything more? My heart went out to them.

Three weeks later, I happened to be walking nearby and detoured to take a look. I found long rows of narrow rock-lined beds where good soil had been added. Thin onion plants and fat cabbages were peeking through a covering of hay and looking perky and content. I thought of the dreams and sweat that had made their mark on this bare place and gave thanks.

Through my paid work, and the tomato seedlings I brought to a meeting to share, I met a family who were trying to grow vegetables in a big lot near their childcare center in a poorer neighborhood not far away. Again, the attraction was irresistible. I arranged for a work meeting at their center the following spring. We talked gardening at the end, and they showed us the little raised beds they had built at one end of the lot. Seeing that expanse of empty space, I spent time over the next several weeks separating perennials and starting a little ad hoc nursery of flowers, vegetable starts, and fruit bushes to share.

Then one Saturday morning, we worked together for three hours: hauling dirt, arranging and planting vegetable beds in the sunny back, and putting all the flowers in a couple of beds out front by the sidewalk. There was much we couldn’t do. That expanse of rubble needed way more soil than we had access to. But we created a place for the children to experience eggplants, tomatoes, and peppers, and a spot of beauty for those who passed by—and I came home with new friends. One shared a jar of his famous homemade barbeque sauce with me, and I brought over a jar of my currant juice and a recipe for currant sorbet in return.

In a neighborhood that was easy to think of as other, I now feel a deep point of connection. My world feels safer; my extended family has been extended and enriched; and it all started with sharing an abundance of tomato seedlings and a love for the earth.

All these ways of supporting the growth of soil, food, and community filled me up, and I was not looking for more. So when a friend of a friend asked if I would be interested in serving on the board of a little urban farm and I listened to the new board chair lay out the need, my first thought was no. Before deciding, though, I would just bike over and take a look.

A ten-minute ride took me into a part of a low-income Black community that was new to me. On this block were houses that had collapsed because they had been built over a creek diverted underground. The water department had invited proposals for the land, and two eager, young White urban farmers had responded. It was a half-acre jewel, rows of vegetables bursting with vitality in the midst of deprivation. The founders had moved on; a major deal with a food outlet had just fallen through; and the four remaining board members were holding on by a thread.

It was something about those vegetables that won my heart; something about the fruit trees planted by the Orchard Project around the perimeter, and those board members who refused to give up; and something about a pure impulse to grow toward the light. As a White-led initiative in a Black neighborhood, the farm was full of everything that is right and everything that is wrong in our society. Saying yes to the farm meant saying yes to taking on racism.

All the growing and sharing of good food and all the wonderful and rooted activities that were offered to neighborhood children happened within the context of an unfulfilled vision of local leadership and ever-present second guessing about the appropriateness of White people like me being involved at all. Finances were tight. Conflicts around gender, race, and class appeared intractable at times. Hardly anything about it was easy.

Yet I’ve never regretted the choice to put so much time and energy over all those years into nurturing this jewel of an urban farm. I’ve loved being around all the people who loved it. One board member, who clearly valued me but just didn’t reassure or comfort my Whiteness, has shown a light on parts of me that might otherwise have gone unexamined. It has been a gift in my life.

After years of intense effort, the farm seems to be on solid ground, with a strong and visionary Black board and staff, stable finances, and ever-growing roots in the immediate neighborhood. I stayed on, as a steady presence and a link to the farm’s history, till it became clear to all of us that they would be fine without me, but the relationships some of us have built in the process are for life.

Rooted in the earth, we are connected to those who have been rooted here before us. We turn our faces toward the sun and the rain. We commit to growth. We acknowledge and tend to the sacred.

Reflecting on all these experiences, from that very first swing of the sledgehammer against concrete to my years with the farm, it seems so clear: urban farming is sacrament. It is a statement of belonging and trust, an alignment with our life-giving home on earth. And by gathering together in this shared love—tending the soil, the seeds, the new plants, the harvest, and the neighbors and children—we can more easily recognize our common bonds and feel our love for each other. Rooted in the earth, we are connected to those who have been rooted here before us. We turn our faces toward the sun and the rain. We commit to growth. We acknowledge and tend to the sacred.

lovely inspirational article. Thanks. Did you ever live at the Bread and Roses house off of Baltimore Street? I once visited there for a month and so enjoyed meeting the people sharing the home. All the best, BarbaraC