Healing Our Communities from White Supremacy and Slavery

Rob Peagler:

Benjamin Lay’s spiritual and social commitment to abolition was sparked and fueled by his direct experience of slavery. Lay and his wife, Sarah, moved to the Caribbean island of Barbados in 1718. It didn’t take them long to recognize the island was a place of “barbarity and ill gott wealth,” as Marcus Rediker recounts in The Fearless Benjamin Lay, quoting Thomas Walduck.

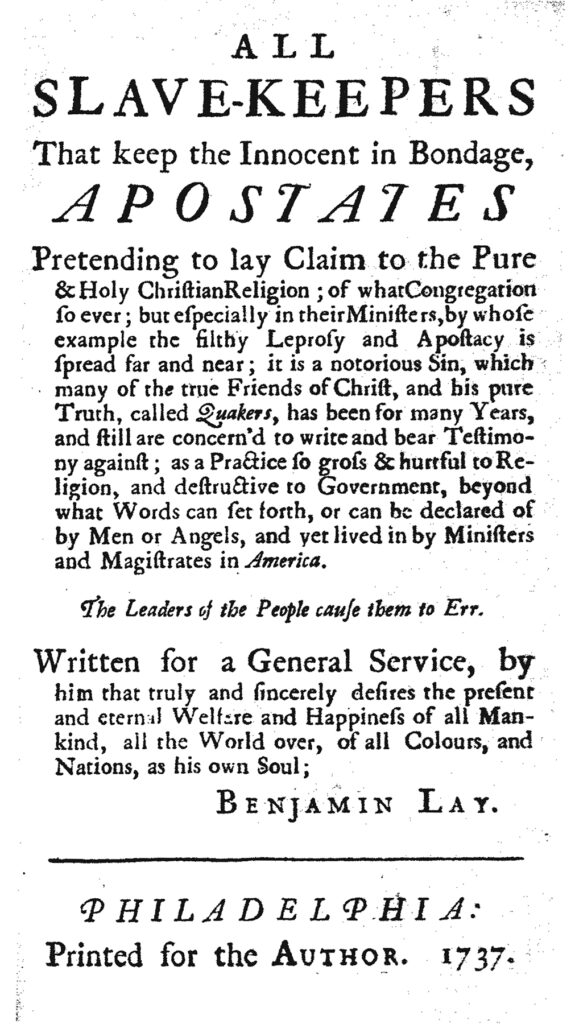

Lay owned a waterfront store, and as Rediker explains, theft was common: “Exhausted, emaciated workers staggered into their . . . shop, buying, begging, and sometimes stealing small items and food.” Early on, Lay responded in anger by whipping a few of those who had walked off with items from the store. Lay recounted in his 1737 pamphlet All Slave-Keepers Apostates:

so when we were in a hurry, one would run away with one Thing, another with another, and so on. Very much we lost to be sure. Sometimes I could catch them, and then I would give them Stripes sometimes, but I have been sorry for it many times, and it does grieve me to this Day, considering the extream Cruelty and Misery they always live under. Oh my Heart has been pained within me many times, to see and hear; and now, now, now, it is so.

He realized, as Rediker recounts, that “this monstrous slave society called Barbados had been built by bigger thieves, who sought not subsistence but riches.” With a clear sense of his personal complicity, and with attendant feelings of guilt, Lay was motivated to be curious and learn from the enslaved.

He talked regularly with an enslaved man who was “a lusty Fellow, a Cooper.” The cooper’s enslaver, Richard Parrot, generated wealth by selling the cooper’s highly skilled labor. Lay learned that Parrot’s efforts to boost worker productivity included a regular practice of “whip[ping] his Negroes on Second-day [Monday] Mornings very severely, to keep them in awe.” Ultimately the cooper was broken under the weight of Parrot’s intimate terror campaign. The cooper told Lay he could bear the beatings no longer, and that, “he would be not be ‘whippe Munne Morning.’” And true to his word, he opted out of Parrot’s inexorable cadence of weekly violence by literally taking his life into his own hands, and killing himself on a Sunday. Lay wrote:

although, as I have said, I saw and heard of such very great Barbarity used toward the Slaves, Night and Day, yet for want of dwelling near enough to the blessed Truth, I was leavened too much into the Nature of the People there which are Masters and Mistresses of Slaves, though I never had nor would have any of my own.

His experience beating enslaved people with his own hands, and listening to his body as he felt remorse for the beatings, as well as hearing directly from enslaved people, supported Lay to be open to Spirit, and to perceive and confront truth, and to strive to be its witness.

Lucy Duncan:

Slavery was not condemned by other Quakers who also had direct experience of it in Barbados. Decades before Benjamin Lay lived there, George Fox visited, as it was home to thousands of Quakers after Mary Fisher and Ann Austin arrived in 1655 and convinced many island residents. By the early 1670s, there were only four Quakers who were not enslavers on the island. In 1671, Fox took a trip and stayed with his relative-through-marriage Thomas Rous who was an enslaver. According to historian Katharine Gerbner, after arriving in Barbados, Fox was sick for two months. His body was telling him something was terribly wrong, but he did not—as Lay had—listen to his body. Many people were concerned that Fox would condemn slavery. Though he did urge Quakers to consider manumission, he did not condemn slavery outright, and instead proposed that Quakers practice a more “mild and gentle” slavery, and worship with those they enslaved.

This was considered to be radical by other slaveholders, as it disrupted Christian hegemony as the justification for enslavement. Clearly, slavery was not an institution consistent with the revolutionary fervor and understanding of the Inward Light of Truth within all people, out of which the Quaker faith had been birthed. Fox had promoted a faith that could include these Quaker enslavers. He chose to protect the Religious Society of Friends as an institution, rather than listen to his body and follow the leadings of Spirit to denounce the cruelty and terror of enslavement among Friends.

Rob:

If White supremacy is a disease, then Lay was not insusceptible, but he did seem to have an uncommonly hearty immune system compared to his White Quaker contemporaries.

And like curious folk who want to know the health routines of people who have lived unusually long lives, I am curious about which attributes and aspects of Lay’s life might have rendered him resistant to epidemic White supremacy. I will share a few aspects of his life that particularly caught my attention.

The first was his proximity and interaction with enslaved Black people during his time in Barbados. I’m also struck by how cosmopolitan Lay was. He had a clear sense of the structure of the global economic system and his place in it. Rediker mentions that Lay was part of a spiritual awakening in the United States and England that was taking place at the time. I was surprised to find that Lay was not the only person in his day who lived in a cave for spiritual reasons, and not even the only one in the Philadelphia metro area to do so.

I can imagine that his social identity and social location may have contributed to his independent thinking and uncommon empathy. An attribute that stands out to me as particularly salient is his work as a tradesperson. Rediker notes that prominent abolitionists of the day tended to be tradespeople.

Lay was also self-taught, and that perhaps supported his tendency to think independently. As a dyslexic person who can describe much of my formal education as “autodidactism-on-campus,” I appreciate this about Lay. I would not find myself unhappy to be living in a nice, dry cave surrounded by a large collection of books that I had carefully curated over the years.

As a little person, his body was out of the norm, and that experience may have enhanced his sense of shared humanity, and allowed him easier access to empathy for marginalized people.

Lucy:

A part of Lay’s radicalization and evident immunity to White supremacy was his experience of the ways in which he was complicit with slavery. Beating enslaved people who stole from his store shook him up, opened his eyes to the ways the system of slavery had impoverished and tormented enslaved people, and provoked him to learn more from those same people. Facing the ways we have been complicit in perpetuating the system of White supremacy is an antidote to its perpetuation. Being able to understand and own the ways we are implicated in a system we did not set up is critical to resisting and abolishing it.

Rob:

Despite his marginalization, Lay offered medicine to heal himself and his Quaker community from White supremacy and slavery in his time. Through his daily actions, he worked to create the New Jerusalem, not only outwardly but inwardly. He didn’t just aim to end slavery. He held a through-line, striving to eradicate all forms of oppression and to be one with all people and with nature.

He understood that truth is a practice and that to truly call New Jerusalem into being, he must manifest it through the way he lived. It was not enough to proclaim, provoke, and pontificate; in order for his witness to have the weight of integrity, he must allow truth to inform every aspect of his life. I am reminded here of something an imam said recently at an interfaith Eid al-Fitr dinner celebrating the conclusion of Ramadan: “We are all each others’ role models.”

In the way Lay conducted his life day-to-day, and with a series of strategic provocations, he embodied and manifested the world he strived to create. Making his home in a cave, tending his garden and apiary, spinning his textiles, and making his own clothes, he created his own commons, with an intention to “avoid the exploitation of the labor of others, including animals,” as Rediker explained it.

Lay took action to “provoke, unsettle, and confound” his fellow Quakers, to cause them to sit up, think, and act: He spattered pokeberry juice on slaveholding Quakers as they sat in meeting for worship; he absconded with a slaveholding neighbor’s child to offer them the experience of having members of one’s family taken away; after being expelled from a meetinghouse for speaking the truth, he laid on the ground at the threshold, so that the congregation was forced to step over him to leave the building.

Lay was the keeper of the sacred flame of abolition, and (despite John Woolman and Anthony Benezet getting much of the credit for abolition among Friends) according to Rediker, attitudes about slavery shifted in the Religious Society most significantly in the decades that Lay was most actively confrontational and outspoken.

Woolman and Benezet did not share Lay’s appetite for outrageous provocation and conflict, but they did align with Lay’s vision by living lives that embraced free produce and connected the just treatment of all creatures with the need to abolish slavery.

Lay laid the way for their quieter approach. He gave his self-published pamphlet, All Slave-Keepers Apostates, to younger Friends, some of whom were children of slaveholders, who then grew to become champions of abolition.

Lay seeded the ground for the action that Philadelphia Yearly Meeting would take in 1776 to make slaveholding grounds for removal from membership. He was cast out, but his influence was deeply felt and meaningful.

It was exciting for us to read Rediker’s description of Lay’s commitment to embodying ideas in public action and “immediatism.” (Our colloquial translation of “immediatism” is that there is no lollygagging or half-stepping on the road to New Jerusalem.)

We share a taste for immediatism. We see reparations as the spiritual descendant of Lay’s efforts to abolish slavery and to heal and rebalance the world. We believe that we all have the capacity to cultivate reparationist consciousness and action. And that we have the power to move toward Beloved Community right now, leveraging our current influence and resources.

Last year, Lucy asked the question: If microaggressions are small, everyday behaviors that bolster White supremacy and other forms of systemic oppression, what might micro-reparations look like?

Can we imagine and test behaviors that interrupt White supremacy and promote healing and repair? In the weave of our daily lives, can we practice identifying harm and instigating repair?

Lucy:

With the medicine of truth and reparations, we need to transform our ghosts into ancestors (to borrow language from Black psychologists Bryan Nichols and Medria Connolly). We also need to transmute our social body, and making reparations is an excellent way to do that.

White supremacy is a deep sickness within the social body, not just here in the United States but globally in colonialism. It runs so deep and is so interwoven in the interstitial tissues that healing the body as it exists may not be enough. That may simply create, as George Fox proposed, a more “mild and gentle” White supremacy. In order to cure it, we need deeper transmutation. Just as the revolutionary faith that we Quakers believe we inhabit may never have existed, the new social body and formation also may not have existed before. That’s not to say that the faith at Quakers’ beginning in the seventeenth century does not have a lot to teach us, but perhaps we are being asked to transform into a creation that has not yet existed. Just healing the body, which has been so deformed by White supremacy, is not enough.

Many racial justice prophets refer to the transformation of caterpillars into butterflies as an apt metaphor for the depth of transmutation that is needed: both within each of us and within the social body. We can’t just reform White supremacy toward justice; we need a whole new kind of creature. After a period of ravenous consumption, the caterpillar finds an appropriate perch and forms a chrysalis. A cell that has been dormant emerges, the imaginal cell or disc. At first each imaginal cell, which contains the blueprint of the butterfly, operates as did Benjamin Lay when he acted as an independent single-cell organism. These imaginal cells are regarded as threats by the caterpillar’s immune system and are attacked, as Lay was. But they persist, multiply, and clump together. They begin to vibrate at the same frequency as that of a butterfly, and act not as discrete cells but as a multicellular organism until the butterfly emerges from the chrysalis and takes flight.

Perhaps Lay was an imaginal cell centuries ago, and the Quaker abolitionists like Woolman and Benezet were able to follow in his vibrational pattern and create the conditions that collectively moved toward abolition among Friends. What does it mean for us today to take on the next stage of this vibrational, visioning work? What does it mean to refuse to be a cell within the caterpillar of White supremacy any more? What does the reparationist social body look like? How do we vibrate at its frequency and teach one another how to transmute into the entirely new multicellular organism that subverts White supremacy and paves the way for the New Jerusalem?

Benjamin Lay was also a vegetarian, a fact that caught my attention as a Black vegan and Quaker attender. While I do not, as some animal rights activists have, equate animal agriculture with human slavery, I have found that ethical veganism has made me more aware of the many injustices in our world, including the ongoing and devastating anti-Black racism in the U.S. I hope more white Friends take action toward Black liberation, including supporting reparations, regardless of whether that idea is popular in their local meetings.

Thanks, Pax Ahimsa Gethen! Yes, the comprehensive just world Lay envisioned is very compelling, and his sense that slavery was connected to all parts seems true, and abolition, real abolition, requires reflecting on and disengaging from those parts. In my experience reparations has been healing for me as a white people, because I was socialized into the idea that my worth was based on my material resources and power over privilege. That’s a hollow way to view oneself, so actively divesting from white supremacy and the lies it has told me as a white person through reparations has been deeply liberating and meaningful. And, yes, honoring the more than human creation is a deep part of moving toward this liberation!