Many Quakers view reflection upon food ethics as a relatively recent phenomenon. In reality, such discernment has been an important part of the tradition of Friends for centuries. Numerous Quaker abolitionists in the 1700s, for example, were deeply committed to vegetarianism as an integral part of their spiritual path at a time when vegetarianism was very rare in the broader culture.

Many Quakers view reflection upon food ethics as a relatively recent phenomenon. In reality, such discernment has been an important part of the tradition of Friends for centuries. Numerous Quaker abolitionists in the 1700s, for example, were deeply committed to vegetarianism as an integral part of their spiritual path at a time when vegetarianism was very rare in the broader culture.

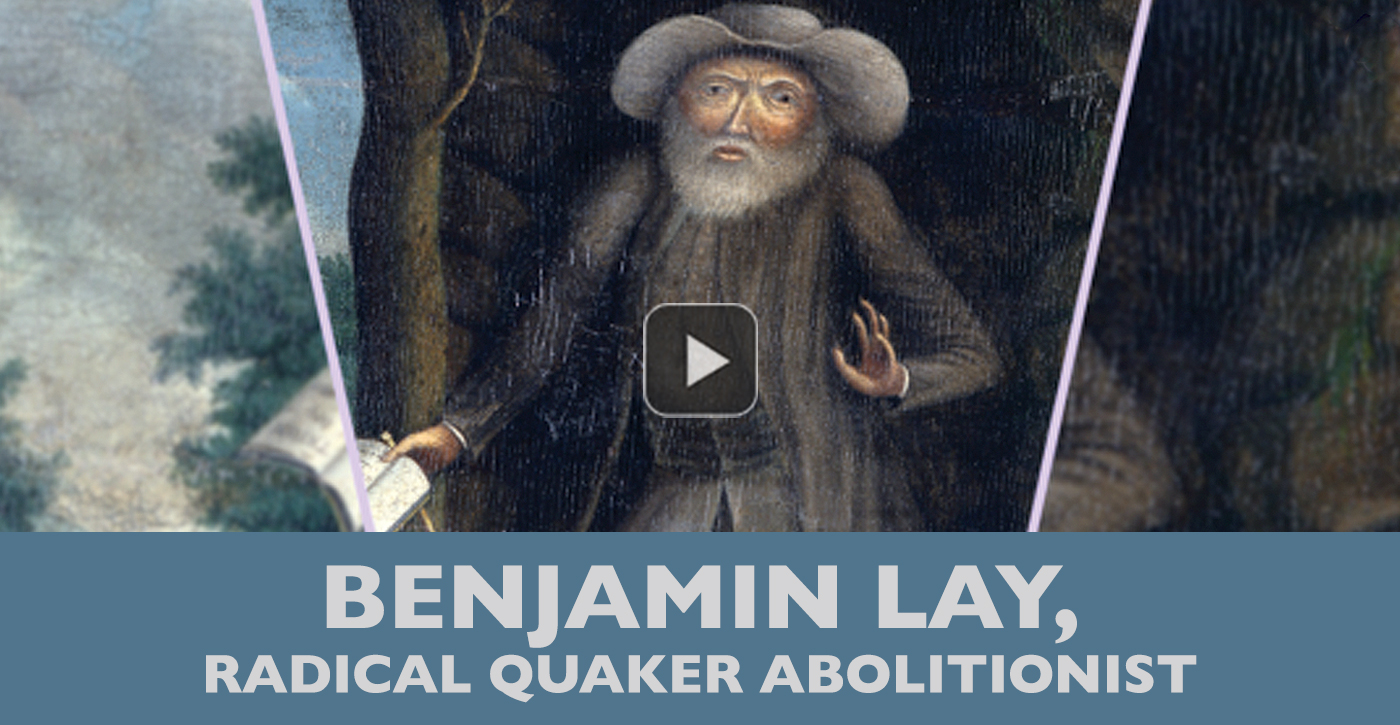

One such committed vegetarian Quaker was Benjamin Lay, whose life and witness has received much attention in the last couple years since the publication of The Fearless Benjamin Lay by the historian Marcus Rediker. Lay was one of the first people in history to call for the total abolition of slavery. Lay’s commitment to respecting all of God’s creatures also led him to a deep concern for non-human animals. It was said of him that “his tender conscience would not permit him to eat any food, nor wear any garment, nor use any article which was procured at the expense of animal life.”

Another vegetarian Quaker abolitionist was Joshua Evans, a contemporary of and influence upon the thought of John Woolman. “I considered that life was sweet in all creatures,” Evans states, “and the taking it away became a very tender point with me.” “My spirit was often bowed in awful reverence before the Most High, and covered with feelings of humility and tenderness,” Evans relates, out of which experiences it was revealed “that I ought no longer to partake of anything that had life.” Anthony Benezet, another well-known Quaker abolitionist, similarly adopted a vegetarian diet, commenting that he had formed “a kind of a league of amity and peace with the animal creation.”

John Woolman shared similar sentiments concerning the status of animals as beloved creatures of God. “To say we love God as unseen and at the same time exercise cruelty toward the least creature moving by his life, or by life derived from him,” said Woolman, “was a contradiction in itself.” While there is no evidence that Woolman ever became fully vegetarian like Lay, Evans, and Benezet, it was written by a friend that Woolman “had seldom eaten flesh.” Woolman also demonstrated his concern for animals in other ways, for example by walking in all of his travels through England in order to avoid contributing to cruelty to horses in the stagecoach industry.

Quaker leaders of the movement for women’s right to vote, in a later time period, were also often vegetarian. Among these women was Alice Paul, a key figure in the movement for women’s suffrage and other struggles for women’s equality in the United States. Speaking of her decision to become vegetarian, Paul stated: “It occurred to me that I just didn’t see how I could go ahead and continue to eat meat. It just seemed so . . . cannibalistic to me. And so I’m a vegetarian, and have been since that time.” Similarly, many leaders of the movement for women’s suffrage in England were vegetarian, including numerous Quakers.

The Society of Friends was the first Christian denomination to form a faith-based vegetarian association, establishing the Friends Vegetarian Society in 1902. Quakers had previously also played a major role in the formation of the Vegetarian Society of England in 1847.

Whereas it has become somewhat common lately to criticize vegetarianism as a white, wealthy elite phenomenon, the reality is that people of color have often been at the forefront of the vegetarian movement, recognizing the deep connections between all forms of oppression and abuse.

This embrace of a vegetarian diet has been shared by many other spiritually motivated nonviolent reformers throughout history. Gandhi, for example, challengingly asserts that “spiritual progress does demand . . . that we should cease to kill our fellow creatures for the satisfaction of our bodily wants.” “It ill becomes us to invoke in our daily prayers the blessings of God, the Compassionate,” he says, “if we in turn will not practice elementary compassion towards our fellow creatures.” Along with Gandhi, some other recent prominent nonviolent visionaries who have adopted a vegetarian diet include Cesar Chavez, Coretta Scott King, Dexter King (son of Coretta Scott King and Martin Luther King Jr.), Thich Nhat Hanh, Vandana Shiva, and others. One striking characteristic of the people in this list is that all are people of color. Whereas it has become somewhat common lately to criticize vegetarianism as a white, wealthy elite phenomenon, the reality is that people of color have often been at the forefront of the vegetarian movement, recognizing the deep connections between all forms of oppression and abuse.

While concern for animals has clearly historically been the main motivation for Quaker vegetarianism, in more recent years other important and compelling concerns have been added as well. These include recognition of the benefits of vegetarianism to human health, the environment, and world hunger. As the Christian Vegetarian Association states, “Modern animal-based diets tend to significantly harm our health, the environment, the world’s poor and hungry, and animals. Since a plant-based diet helps to address these concerns, we see it as an opportunity to honor God.”

References

Geoffrey Plank, “‘The Flame of Life Was Kindled in All Animal and Sensitive Creatures’: One Quaker Colonist’s View of Animal Life,” Church History 76:3 (2007): 569-590. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27645034?

Samantha Jane Calvert, “Eden’s Diet: Christianity and Vegetarianism 1809-2009,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Birmingham (2012), pp. 163-201. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/4575/

Donald Brooks Kelley, “‘A Tender Regard to the Whole Creation’: Anthony Benezet and the Emergence of an Eighteenth-Century Quaker Ecology,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 106:1 (1982): 69-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20091642?

A Journal of the Life, Travels, Religious Exercises, and Labours in the Work of the Ministry of Joshua Evans; select quotations from the journal available at https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Joshua_Evans_(Quaker_minister)

“Conversations with Alice Paul,” an interview conducted by Amelia Fry (1972). http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt6f59n89c&doc.view=entire_text

Love it…viva Planet Earth…viva Vegetarianism…viva Quakers…

GREEN, because:

there is NO planet “B”

There is one glitch in a purely vegetarian diet and that is vitamin B12, which is only obtained in animal-based food products. This vitamin is essential To health; its absence produces anemia and/or neurological disease when levels are too low.

Even people with some meat in their diet may have low B 12 levels. Vegetarians and stricter vegans should obtain a reliable source of B 12. For the past 50 years or more, it’s been available over the counter as a vitamin supplement.

Friends, let’s think about all becoming vegetarians and the consequences both intended and unintended. Perhaps by eliminating all animal products from our diet we would be a healthier world. Those of us who still had a job. Here in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia we are an agricultural community. One of the products we grow and process is poultry. A large number of the workers in the poultry plants are immigrants who earn a wage and support their families. Farmers raise the chickens and turkeys and the corn used to make the feed. Feed mills with their employees turn the corn into poultry food. Truck drivers deliver the feed to the farmers and the birds to the poultry plants. And many more businesses support this industry. So if we all quit eating poultry, what happens to these workers? What about the KFC stores, the Popeye Fried Chicken stores, the other restaurants which serve poultry? How will those employees fare?

In our home we eat a balanced diet which includes animal products along with locally produced vegetables from the farmers market and groceries. We celebrate the opportunity our recently arrived neighbors have to work in local industries and in the companies which support them. Is it not also “honoring God” to provide a safe place to live and employment for those escaping hunger and violence in their home countries?

When we advocate eliminating entire industries, let’s please think through the intended and unintended consequences. Just look at what happened to communities who depended on coal for their livelihood.

We shouldn’t intend to build industries to perpetuate the act of harming animals. Through human history people have had to adapt to changing career needs. The idea that we should keep on eating animals to help support jobs is not compassionate.

Respecting sentient beings must always come before employment considerations. Cruelty to animals can never be justified, especially when it is a simple matter to make choices that benefit human health, animal welfare

as well as concern for the environment. Those who consider such choices usually demonstrate a higher level of morality.

thank you for sharing this article with us. here in western Massachusetts as a member of Mt Toby Friends meeting for quite a number of years I felt ‘out of place’. still remain a member of the meeting but no longer attend. very pleased to read there were historical Quakers choosing to be vegetarian so as not to harm animals. and pleased to learn of a Friends Vegetarian Society. this is the first time I have read of it. thank you.

I am so happy with this article!

To be honest, I do not understand how you can serve the problems of environment, scarcity of water and zo on better than being a vegeterian. In the Netherlands not many Quakers are vegeterian…

With love, Johanna Hofman

Greetings from Vancouver Island, Canada!

This is such an inspiring article. My husband and I eat a primarily vegetarian diet for personal and planetary health reasons. I am inspired by the spiritual teachings in the article to eat a completely vegetarian diet.

Thank you, Friends, for sharing the article.

True, but logically a Plant-based diet takes compassion to the next level. Being vegetarian only eliminates a small percentage of animal suffering, and does not address the slaughter of day old male chick’s to produce eggs, or ofmalecalves and later their mothers when they fail to produce the required amount of milk. And, consider that humans are the only species to consume the milk of another species. BbB

There is a tradition of vegetarianism amongst British Quakers, for example the Quaker politician T. Edmund Harvey (1875-1955).