I transitioned to a plant-based diet, as a matter of moral conscience, about seven years ago. Another word for it is vegan, which means that I refrain from eating foods derived from animals. This was the result of a come-to-Jesus meeting that I had with myself, during which my conscience wanted to know why, as a person who had always considered herself to be an animal lover, I was eating them.

It turned out that my solitary 25-minute drive to silent worship at the small Friends meeting I attend in rural, southeastern Pennsylvania yielded something precious: exposure, on my own terms, to the tremendous suffering that farm animals endure. I stress the importance of it being “on my own terms” because until this point I was one of the legions of animal lovers unconsciously living with blinders on. The blinders were there to avoid the emotional upheaval inherent in crossing barriers vigorously maintained by the animal farming industry, for the mutual protection of animal farming and animal-lovers-in-denial.

My conscience was called to action by a sign—not one in which the clouds part to reveal a singular beam of insight, but an actual, man-made sign, posted alongside the road in front of a farm. It was a plain white placard-style advertisement attached to a free-standing black frame, similar in dimension to the ones that advertise the latest news headlines on London street corners. In London, those signs, situated as they are among so many visual stimuli, battle for the viewer’s attention, but this one was surrounded by hundreds of acres of open space, thereby elevating its status to that of a landmark. In black capital letters that were machine-made and interchangeable, it read:

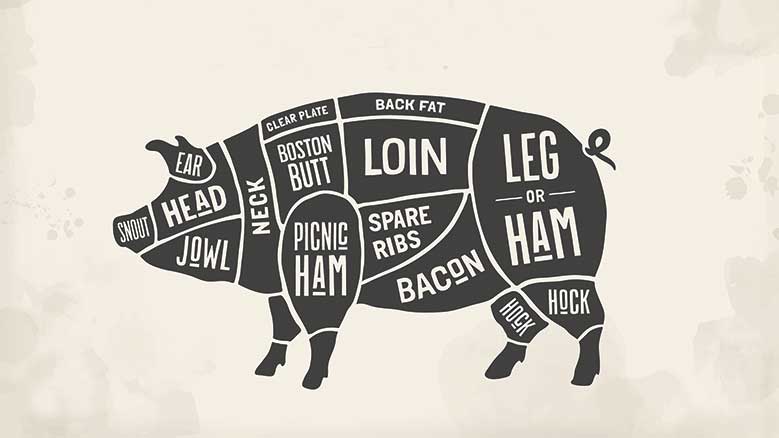

BUTCHER HOGS

FOR SALE

A phone number followed.

The violence of the phrase “butcher hogs” unnerved me, presented so matter-of-factly like a news headline and nestled within a picturesque scene of gently rolling fields, anchored here and there by family farms. My first tormenting thought was that the sign’s harsh wording might define this farmer’s orientation toward the vulnerable animals in their care. My next was to wonder if anyone would bother to check.

In the incubated realm of mainstream American culture, pigs—a nicer word than “hogs”—aren’t slaughtered. Like other animals we consume as food, they are harvested, like pumpkins at Halloween, or processed, like an insurance claim.

Behind the plain white sign advertising “Butcher Hogs for Sale” sat a plain white single-story house, with white vinyl siding and white window blinds, drawn closed. To the right of the house, but at some distance from the road, stood a pair of long, windowless, above-ground tunnels, with large turbines built into their walls at one end. To the left of the rectangular tunnels, a cluster of weathered buildings presented as the original farm, before its transformation into what appeared to be a family factory farm. I was left to hope that these sensitive creatures were not living out their lives like mushrooms, Pennsylvania’s star fungus. But I soon learned that big, above-ground tunnels do in fact house pigs for life, and smaller ones, chickens. And because I have now spotted several examples of each in the area, I am left to conclude that the care pigs and chickens receive in this unnatural scenario is conspicuously poor and completely normal. To date, the only sign of life I have seen on the property is a uniform covering of closely mown grass.

On one of my early trips past “butcher hogs”—as if these animals were born to be slaughtered—I summoned my inner smart-ass for protection by envisioning a clever ax murderer who moves out to the country in search of a socially acceptable way to ply his craft. A subsequent drive-by took a different turn. This time, I acknowledged that what this wording amounted to was a breach of etiquette. When marketing their products, sellers of what is politely called “meat” are expected to use language that deliberately shields consumers from the truth. “Flesh” is okay when describing the interior of a tomato or watermelon but too raw when naming the actual flesh of sentient beings. More than just a courtesy, this dance is vital to the sellers’ preservation. In the incubated realm of mainstream American culture, pigs—a nicer word than “hogs”—aren’t slaughtered. Like other animals we consume as food, they are harvested, like pumpkins at Halloween, or processed, like an insurance claim.

Because my thinking was shifting on its own, what happened next was uncanny. The sign’s wording, which had remained static for months, suddenly changed. Now, instead of “Butcher Hogs” for sale, they were “Roaster Pigs.” True to my cultural training, I instantly cooked up a winsome image of a pig standing on his hind legs, wearing a tweed blazer and wool scarf. Nothing else about this unsettling scenario had changed, but these two new words, with their sense of mirth, offered some temporary relief:

One little piggy goes to market; one little piggy stays home.

One little piggy has roast beef; one little piggy has none.

And one little piggy goes, “Wee, wee, wee,” all the way home.

It didn’t last.

How many times in life had I been confronted with a cartoon pig used to advertise the sale of its species’ body parts? This particular pig stands on his hind legs, as a human would, wearing a chef’s hat and apron and holding grilling tools. I have seen him in the meat aisle at the grocery store; advertising barbecue for church fundraisers; and announcing the menu in college cafeterias, and I bet you have, too. What would a psychiatrist make of our culture’s practice of selling an animal by first, rendering that body as a cartoon, then dressing it in human clothes, and propping it on two feet, poised to roast a member of its own kind?

On a morning when I am not teaching at a local university, I assist as a volunteer in first- and second-grade art classes at my daughter’s school. There I have observed that when tasked with drawing a house, these little children of the twenty-first century will often produce architecture rooted firmly in the nineteenth, including mullioned windows, roofs with steep-pitched gables, and stout brick chimneys puffing smoke. Their farms are vibrant, springtime places, where a variety of animals—but never too many of one kind—have universally clean fur and feathers and plenty of open space. My own overdue confrontation, at 42, with the realities of animal farming made me question if our understanding ever really matures much beyond the first grade. When asked to picture a farm, how many American adults would conjure above-ground tunnels in a void?

In southeastern Pennsylvania, many family farms have been razed and replaced by housing developments accommodating transplants from nearby industrialized suburbs. Over the years, newcomers have developed a reputation for showing up at township meetings to complain about noisy roosters and the smell of manure, provoking disdain from seasoned farmers who wonder if these people realize where their food comes from. But the reality is that most American consumers are not in command of the whole story, which frees advertisers to cater to our collective inner first-grader.

I quickly realized that nursing was not just about nourishment. It was also a real source of comfort for my newborn, and for me, wanting to soothe her.

My own love for animals was nurtured as a child when I lived on a dairy farm that belonged to my paternal grandparents. My father and grandfather were the farmers, and my family modeled kindness to animals. My dad’s unusual rapport with them remains a source of admiration and wonder. His friends included dogs, cats, cows, and a young barn owl who left his family behind in the top of a silo to follow him around the property as he went about his work. My dad protected the cows from impatient motorists pressing the line when he brought them across the road for milking. He played music for them in the barn, having observed that it relaxed them. As a family, we tried our best to save the small animals and birds orphaned by the plow, and we took into our lives the castoff pets that people pushed out of their cars and onto our property. One night, shocked by the sight of flames coming from the barn during a renter’s tenure, my father, who was at home getting my little sisters ready for bed at the time, ran from the house into the burning building in his bare feet to save three of the renter’s calves who were left there to be incinerated, along with the insured equipment. The fire was ruled an arson.

Another life experience informing my decision to switch to an animal-friendly, plant-based diet was nursing my baby. As a new mother, I quickly realized that nursing was not just about nourishment. It was also a real source of comfort for my newborn, and for me, wanting to soothe her. I usually nursed at home, in the privacy of our apartment in San Francisco, but also under a blanket in the backseat of cars, and while hidden in the leafy recesses of Golden Gate Park. Having to sneak around to feed your baby is a good reminder of the fact that contrary to our training, we humans are mammals, too.

Sadly, likening myself to a cow, who spends her life being impregnated only to have her newborns cruelly taken from her, is an insult in our language. When I have asked my first-year college students to explain the negative connotation that “cow” carries, they have told me that cows are women who are loud, sloppy, and undisciplined; cows don’t take care of themselves. Some of the qualities that we ascribe to animals, often with no basis in fact, are so deeply ingrained that they appear in the dictionary alongside the denotations, indicating a similar weight of authority. But then there is the verb “cow,” meaning “to frighten with threats or a show of force,” which is what enables us to steal the babies and seize the udder milk from these gentle herd animals. In her book The 30-Day Vegan Challenge, vegan chef Colleen Patrick-Goudreau writes, “there is no nutritional component of cow’s milk that makes it any more necessary for human consumption than, say, hyena’s milk.” Imagine that scenario.

Nutritional scientists have assessed the United States to be in a degenerative state nutritionally because of the prevalence of lifestyle diseases due in large part to poor dietary choices that so many do not even realize they are making.

During my own nursing days, I saw a scene in a movie in which a man reaches into the refrigerator to grab some cream for his coffee. After he begins drinking it, he realizes that he has mistaken human breast milk for cream. Maybe it was his wife’s or his friend’s wife’s, I can’t remember, but when he realizes his mistake, he makes quite a show of spitting it out. In our culture, an adult male human drinking a human mother’s breast milk is taboo, but there is nothing wrong with crossing species to deprive another newborn of mother’s milk and her loving bond. When I asked my dad, the former dairy farmer, what that process of separating the calf from the mother was like, his answer was clear: “Sheer agony for both.”

That said, the answer to this question of why I was eating animals, and therefore participating in their misery and torment, while simultaneously “loving” them, was obvious, right? Humans need to eat animal products to maintain proper nutrition. But my conscience pushed me to give that some hard thought. That was the easy answer—so easy that I had not even come up with it on my own. I had inherited it, in the same way that my dad had inherited dairy farming. He had gone to college and earned a degree in animal science, planning initially to become a veterinarian but ultimately returning home to help his father run the family farm—the only one of five children to make that a priority.

My conscience was going to give me an extension on defining proper nutrition, warning me that the evidence would have to be credible. In the meantime, she wanted action. So I went to the library, not to survey trends in dieting from the comfort of a wingback chair, but to zero in on plant-based cooking. We weren’t there to mess with desserts or appetizers. We were on a brisk walk to “entrees.” How do you feed your family a delicious, nutritionally sound meal made solely from plants?

Having since mastered that challenge, eating a plant-based diet has continued to let the light in. The most heartbreaking aspect of it has been the realization that the tremendous scale of animal suffering is not only an unnecessary extravagance but also detrimental to human health. Nutritional scientists have assessed the United States to be in a degenerative state nutritionally because of the prevalence of lifestyle diseases due in large part to poor dietary choices that so many do not even realize they are making. In fact, the current generation of children is the first in history projected not to outlive their parents. The imposition of our unhealthy diet on the developing world has significantly increased the burden of disease in those countries. They are now contending with high percentages of lifestyle diseases, in addition to communicable diseases. Even the U.S. Department of Agriculture has stated that Americans are eating far too much animal protein.

I have three cats, who are obligate carnivores—unlike some humans who only imagine themselves to be, while their colons beg to differ—so my grocery cart will never be completely free of animal products. But my immediate and extended family is now vegan, including my mother, who was confronted with a high cholesterol count, while I was contending with a troubling sign; my father, the former dairy farmer; and most recently, my sister, a professional chef. Eight months after converting to a strict plant-based diet, my mother no longer had high cholesterol. Years later, that has not changed.

I continue to make the same drive to my Friends meeting, a plain brick structure built according to tradition in 1823 to look more like a house than a church. Its purpose is made clear by one sign that identifies the building, and two more that announce to onlookers our faith’s strong commitment to peace: “Friends for Peace” faces the road from a window, and a banner that reads “There is no way to peace; peace is the way” hangs from a stretch of wrought-iron fence lining the property.

But several years ago, “Butcher Hogs for Sale” became a translator for me, re-casting familiar messages and experiences in high relief. Like so many Americans, I routinely head to a supermarket to buy food for my family. It is an outwardly peaceful place—with its soft lighting, controlled climate, and soothing music—but if I go there to buy foods derived from animals, packaged discreetly to bear little resemblance to their origins, I am, in reality, paying other people to facilitate an animal’s prolonged suffering and premature death, making me cruel and violent by proxy. So in the light of so many other nutritious, delicious, and affordable options, I’ll refrain, and I hope that you will join me.

Note from the Editors

The print edition of this article included a photograph of a sample notice board provided by the author. It included a phone number, which the author asked Friends Journal to crop out if we decided to publish it. We fully intended to follow these wishes but missed it while preparing the issue and the full photograph was printed. We apologize for this omission.

While NOT a vegetarian myself, I am a proud and vigilant Quaker, First and Foremost.

The world turns full-circle (eventually) and sooner or later will come a time when we find ourselves morally reprehensible for our actions, both for actions of self-focused aggression towards those of our species (Homo Sapiens), but also to those who are unable to defend themselves in order to live a natural life, free from suffering, both from members of their own species, but from others (i.e. Homo Sapiens) Pigs/Hogs fall into this category, and briefly stepping aside from Quakerism I still find that to kill (or to pay someone else to kill on my behalf is, in my own view immoral). and as a Quaker, offer my earnest support to the author’s views.

In Friendship

So I wonder if this belief extends to all living things, including flies and mosquitos. In addition, I’m curious how the belief that no “killing” extends to embryos?

I stumbled across this dissertation and read it in full.

The author has come to a life realization. She feels compelled to educate the rest of us to what that is.

She in entitled to her beliefs.

We are all connected. We all have life force. God appointed us stewards of the earth and all in and on it. We have a responsibility to act in a caring and responsible manner in how we treat each other and that said other life forms. A rooster is no different than a dog when he knows you, same as a pig, a cow or any game animal.

I do agree man has divorced himself from the source of his food. It is processed and repackaged and marketed as something else than what it was originally.

Man is a flawed creature. But there are some of us who try to do better who realize it is up to us to be the “better person”.

Not eating meat has nothing to do with that.

Follow your conscience, that is your soul speaking to you.

Thank you for a wonderfully thoughtful, thought-provoking, introspective, spiritual article, Dayna Bailey. I stopped eating meat three years ago for three reasons: health, humanitarian, and ecological. You’re right — animals are sentient beings and mammals share many traits in common. They’re family-oriented, care for their offspring, feel fear and pain, have memories, and many know when they’re going to be slaughtered.

You deftly break down the arbitrary distinctions some of us make. But there really isn’t much difference between a pig, or, cow, or chicken, and a dog. While I try to understand and allow some cultural accommodations, when I see pictures of depressed dogs in over-crowded cages in Asia, waiting to be slaughtered, feelings of primal violence well up in me toward those who do that.

Whales and dolphins are highly intelligent mammals — relatives of ours, actually — who have been on this planet far longer than we have. And though I don’t agree, I can understand how some Pacific or Alaskan tribes wish to continue strictly limited whale hunting because it’s been part of their culture and belief systems for thousands of years. But I see that as distinctly different from wholesale slaughter of cetaceans for supermarkets in Japan.

Things get murky and not all species are equal. Pests like rodents carry disease and invasive species like boa constrictors and iguanas are wreaking havoc in the Everglades, destroying native animal species. Similarly, along the Mississippi, the invasive Asian carp population has exploded, destroying native species and are intent of making their way upriver to the Great Lakes. They are so prolific and aggressive, that they sometimes attack rowers paddling down the river, and they literally jump into powerboats, flying into the faces of boaters. It’s the kind of ecological crisis that results when thoughtless people dump exotic pets into ecosystems in the U.S., which have no natural predators to keep their numbers in proper balance. We are all connected to the circle of life.

I have friends who are ardent vegans. But this issue gets murky for me because plants are sentient beings, too. They can tell the difference between their roots, and something that is not their roots. Trees can communicate chemically by alerting others of oncoming pests or disease. When I look at the little herb garden in my sunny kitchen window, I sometimes feel a bit like a cannibal or a vampire — because I’m growing those basil plants to “harvest” them for my dishes. There’s something a little ghoulish about that. So, for me, there’s not a lot of difference between that basil and a chicken. So, to draw a strict line between what we will and won’t eat seems a bit like simply splitting hairs in some ways.

Every drop of water we drink and every breath of air we take have living organisms in it. The challenge is where do we draw the line ethically, ecologically, and practically? It’s as you said, a matter of spirituality and stewardship. I still eat a greatly reduced amount of wild caught, sustainable sea creatures, mostly bivalves. But I often think of Mister Rogers who said: “I never eat anything with a face. And that’s my goal.

Global climate change is our greatest danger, as even our military acknowledges. This means, we need to make different choices regarding the foods we eat. One of the reasons I stopped eating meat was because I could no longer justify the 600 gallons of water it takes to produce a single beef hamburger. I can live without burgers, but I can’t live without water. And I want my child, and hopefully grandchildren someday, to always have clean water to drink. I owe them that.

The next round of wars will be fought over water, not oil, which has already begun in east Africa. The perfect storm of higher average temperatures due to global warming, record years of drought, massive agricultural farms (“Big Agra”), and dramatically increased populations in arid places, like Las Vegas, are depleting the Oglala Aquifer and other natural water sources faster than Nature can replenish them. And industrial pollution that renders drinking water to be as toxic, or worse than Flint, Michigan’s, in a thousand other communities across the country is expediting this crisis.

But there are also water-villains in the plant world, too. It takes one gallon of water to produce one almond. Avocados are also water guzzlers, which require 74 gallons each. Peaches require 42 gallons apiece. We have the intelligence and technology to engineer crops that are more drought-resistant, requiring less water. But each of us needs to make good choices about the foods we buy, and “vote” with our informed dollars.

I’ll save my next homily about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch the size of Texas, and others swirling around our oceans, for another article. Or, how pesticides are now being found in mother’s breast milk and intact chicken eggs. We’re a suicidal species that also destroys other life forms. Yet this is the only planet we have.

I believe that we, as Quakers, are called upon to be ever better stewards in our little corner of the world wherever possible. As George Fox said, “be examples” to others. Today, there is an abundance of plant-based protein — burgers, sausages, ground “meat,” roasts, and seafood substitutes — that taste as good as, if not better than, animal protein. I encourage those who eat meat to reduce their intake, if not for personal health, then, for the health of the planet.

Even major corporations are getting on the band wagon. Perdue is coming out with a chicken burger that is half plant protein because they see this shift in consumer consciousness, preferences, and diets. Burger King and White Castle are now offering burgers produced by Impossible Foods. And Citizens Bank Park is now selling vegan cheese steaks using plant-protein “meat” from Impossible Foods, inspired by Philadelphia jazz musician Questlove.

Thanks again for your thoughtful, spiritual, and wonderful article, Dayna Baily. Thee speak my mind, Friend.