Holding Firm to Multiple Religious Connections

One way in which Quaker communities connect with other religious groups is through individuals like me who are active participants in more than one religious community at the same time. In the academic literature, this is often called “multiple religious belonging.”

What is my religious position?

Before anything else, I am a Quaker. I grew up as a Quaker, and I have chosen to stay with, study, struggle with, and work within the Quaker community. But my Quakerism is flexible. A core part of my Quaker understanding is that we should be open to learning new things, and over the years, my spiritual journey has also taken me into other communities.

As well as being a Quaker, I am a Pagan—specifically, a Druid. Very specifically, I am a member of the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD). They run a correspondence course that has been nourishing me for many years now. I really value the focus the Pagan community has on the natural world and the divine feminine; I think both bring important balance to mainstream society’s emphasis on centering the human and on male dominance. I also appreciate the way OBOD approaches connections to the past, holding together in creative tension the desire to connect with ancient Druidry while acknowledging that we know very little about it. (And some of what we do know, we might not want to keep.)

As well as being a Quaker and a Druid, I have connections to the Buddhist community of the Order of Interbeing. Presently, I don’t manage to attend their meditation groups regularly but every month keep up the practice of reading the Five Mindfulness Trainings. Thich Nhat Hanh’s Engaged Buddhism sits well alongside Quaker activism, and the Five Mindfulness Trainings ask me to assess regularly whether I am acting in accordance with key principles. Often I am not, of course, but sometimes I can identify specific areas to work on. Like any other mindfulness practice, it isn’t about achieving the goal of being constantly aware but about gradually improving awareness and developing the ability to consider and act differently in the moment.

As well as being a Quaker, a Druid, and a bit of a Buddhist, I’m comfortable articulating Quaker perspectives in relatively traditional Christian language. At the moment, I represent Quakers in a church leaders’ group for my city, and I feel strongly that we should keep up those ecumenical links wherever we’re welcome, even though we’re apparently very different from other churches that join such groups. I’m not suggesting we hide our theology to do so but that we should believe others in those spaces who say they want to hear from us, even when they don’t agree with us and when it seems as though we might not count as “Christian enough” by some set of rules or other.

This raises some major questions. Among others, we might want to ask: What does it mean to be in a particular religion? Is it really possible to be part of more than one religion at once? Aren’t there rules, actually, about what counts as Christian or not? What does Rhiannon think she’s on about with this incoherent bundle of eclectic nonsense?

Fair questions. One useful place to start, I think, is to consider what being part of a religious tradition involves.

Sometimes we imagine a religious tradition as a package deal, like a set menu: if you’re a Christian, you get these beliefs, those practices, and this community, all served together. For some religious communities, that may be true or at least the way everyone would like it to be. However, in reality, even if I’m served a set menu, I can choose how to eat it: I can leave the mushrooms because I don’t like them, put the sauce intended for one dish onto a different one, and so on. Religious traditions aren’t static or pure, and the people within them are active participants in creating their tradition.

Another way to look at it would be to see a religious tradition as a recipe: this is the way things have been done before, but individual cooks adapt to their own needs and circumstances. Instead of just leaving the mushrooms on the side of the plate, I don’t even have to include them in my meal. In the same way, members of traditional Christian churches who struggle with some particular belief or part of the liturgy can choose many different approaches to live with or handle that. Those who aren’t sure about the Virgin Birth; using only masculine language for God; having a huge, mostly empty church building while people are homeless outside; or many other possible worries can affect their church experience to some extent.

For example, we see people still identifying as Christian but attending church rarely or never; changing denominations to find a better fit; attending with their families but ignoring unwanted parts of the liturgy; wrestling alone or in study groups with difficult Bible passages; actively suggesting changes and writing prayers that use different terms; doing charitable work as part of or alongside church involvement; taking leadership roles to make changes in the church; and choosing which parts to include in their lives outside church services. Even if the shared worship service isn’t open to much change, people’s prayer lives at home and their engagement in other practices—such as saying grace before meals or donating money to the church—are areas of choice and negotiation.

Another way to look at it would be to see a religious tradition as a recipe: this is the way things have been done before, but individual cooks adapt to their own needs and circumstances.

If we apply this approach to my situation, it will be clearer how my multiple religious belonging works in practice. We can start with the background against which my religion (and the rest of my life) is set: in the culturally Christian context of British society. There are plenty of things in British culture that I struggle with (sexism in society, class structures, embedded racism and transphobia, widespread alcohol use, and so on), but for the most part, I’m not fighting the Christian elements of society. I grew up celebrating Christmas and Easter, and it suits me well enough to have days off of work at those times of year and to have shops with different opening hours on Sundays. The history of Quakerism as a church means that it’s recognized in law for the purposes of charity registration, holding marriages, and other things. In general, I have the privilege of going with the flow of the Christian background. It is mostly background: the things that affect everyone, like the timing of bank holidays, don’t affect me negatively, and I can mostly pick and choose from the rest.

I choose to engage in other religious traditions as well. The background level of Christianity provided by the cultural context isn’t enough to satisfy my interest in religion, so I add to it both explicitly religious practices, like attending meeting for worship, and religiously motivated practices, like trying to make ethical purchasing choices. When I talk about explicit religious practices, I’m thinking of things where the main purpose is religious: to connect to my spiritual life, to feel closer to God, to develop my theological understanding, or to deepen my faith. For me at the moment, those things include attending Quaker worship, studying Quaker history, doing Druid visualisations, reciting the Buddhist Five Mindfulness Trainings, and going for a walk in the park. Some practices are easily associated with particular traditions: my meeting for worship isn’t just a Quaker one; it’s a twenty-first-century Liberal British Quaker meeting for worship in a meeting that welcomes Christian, Universalist, nontheist, and many other complex understandings. Other practices are not especially linked to a tradition: sometimes I might set out to go for a walk Druidically, noticing the presence of symbolic plants and animals or the turning of the Wheel of the Year; sometimes I might walk in the park in a mindful way informed by Zen Buddhist teachings; and sometimes I simply go for a walk as my whole one and complicated (and frequently distracted) self.

Perhaps these examples blur the boundary with religiously motivated practices. There are times we might have religious reasons for doing certain practices, but they aren’t necessarily on show. For example, like many people, I try to make ethical choices in the things I buy. I can explain—if someone asks me—that I’m trying to buy recycled products to reduce the negative effects consumers have on the environment and that I understand my choice to be a religious obligation to co-create a better world with an immanent Divine force. But of course, mostly people don’t ask.

The company I’m buying from probably doesn’t even have a way to ask me about my reason for buying their item. All they know is that they’ve sold this many units of their product. Even if they did ask, it would be understandable if they didn’t get it or even listen all the way to the end.

Lack of articulation can be a problem when we are thinking about religious belonging: most of the time, most of us aren’t called to explain our motivations, and we don’t know why other people do what they do. How can we work out what’s religious? But not having to go into theological detail can also be an advantage when we work together with others. We might be helping at the food bank for different reasons, but if we’re all helping and the work gets done, we can leave the discussion about motivations for another day.

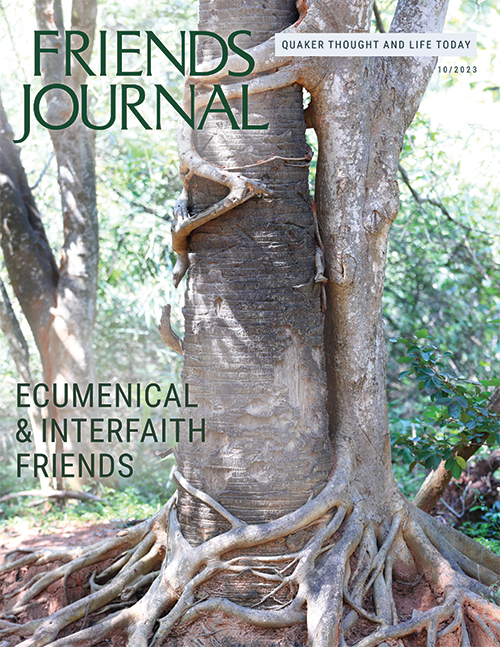

When I imagine the liberal Quaker branch of the Christian tree, I think of those situations where a tree branch bends down and touches the ground and sends out roots of its own. It’s still part of the original tree. . . . It’s also a whole tree of its own that can stand alone and draw new resources from the new ground it has found.

I hope this helps to put the complexity of religious positions into perspective. These overlapping and multiple factors are how I can be part of more than one religious tradition, and sometimes act from one, several, or perhaps none of them. What does this mean for the Liberal Quaker community?

It may mean we need to let go of some ideas about what it means to be part of a tradition. For example, some of us would dearly love for there to be a yes or no answer to the question of whether Quakers are Christian. It would make things much neater and easier to explain. It would mean less worrying about whether to join ecumenical bodies and would clarify the situation for individuals who know that they are or are not Christian themselves. But my analysis of religious complexity suggests that there will never be a simple answer.

When I imagine the Liberal Quaker branch of the Christian tree, I think of those situations where a tree branch bends down and touches the ground and sends out roots of its own. It’s still part of the original tree: the branch that is bent can pass water and nutrients back and forth. It’s also a whole tree of its own that can stand alone and draw new resources from the new ground it has found. Is this one tree or two? It’s not really a useful question. It would be better to ask the gardener’s questions: Can we make space for this new growth? Does anything here need pruning? Is there enough water? In a drought, all the plants in the garden will have common cause, and the question about the dividing line between this tree and the next tree and their linking underground fungi is irrelevant.

Our lack of specificity about Christian faith means that we can say, “This is the way we do things,” clearly and confidently, without any disrespect to communities who do things differently. We need to respect and trust our own abilities to shift between different contexts and sets of rules—much like how people can move between formal and informal, child-friendly and adult, or multiple languages—so we can and do move naturally between different religious spaces. Quaker worship and silent meditation have some things in common, but they also have some different expectations, such as the possibility of giving spoken ministry. Practicing both regularly may make it easier rather than harder to understand their differences and what effect they have upon our feelings and actions. In the same way, practicing a second language regularly makes it easier to switch in and out of different grammatical structures. Meeting for worship for business and our discernment processes have their own particular guidelines and social norms, and we can explain them by teaching those who are new as well as reminding each other. Even in my native language, I have to look up some spellings over and over again. (I don’t know why available is so difficult for me!) We can remind one another about the parts of our discipline people commonly struggle with or tend to forget without having judgement or an expectation that one day we’ll be able to stop.

Finally, our lack of specificity frees us to follow the Light Within. Our roots can grow in new directions without losing contact with the existing branches of our tree. We can put in the work needed to learn about another religious tradition in the same way we might learn a new language: with full respect for the boundaries that protect and support communities, aware that those boundaries name our many differences and do not override our similarities. We can welcome diverse individuals, articulate our shared understandings, and be ready to change when we discern together that it is right. We can stay with our tradition in a balanced way: neither holding tight to things that aren’t helping us nor rejecting the good just because it’s old. In short, we can discern the difference between the baby and the bath water.

It will not always be easy: like with a recipe, adapting it for a new kitchen or substituting different ingredients often requires repeated testing before it’s just so. On the way, we can welcome people who have experience with other cooking techniques and cuisines. Practicing Paganism or Buddhism isn’t the same as practicing Quakerism, but for me they are mutually supporting.

Love the cooking analogy, as creating great new fusion dishes involves many experiments before appealing broadly. Ashoka sent Buddhist emissaries to the middle east a few centuries before Jesus, allowing enough time for cultural sharing and fusion within the Roman Empire to influence Rabbi Jesus’ discernment. The Dalia Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu got along very well together. Regarding Pagans, it may be important to remember you can find God in nature, but nature is not God, which is similar to comparing ideals to reality, where balance is important. The internet is expediting religious diversification and fusion for our younger generations globally, and interactive faith experiences at home are rapidly approaching to save resources to share with our 8 billion human friends, plus all our animal and plant friends.

Would prefer ‘days off work’ to ‘days off of work’! But a lovely article Rhiannon which explains a lot. Enjoyed the Author Chat too.

Next year’s Quaker Universalist Group (UK)’s Conference at High Leigh is on the theme of ‘the future of religion’ (across the world) – and the future of Quakerism and Quaker Universalism and in that context I came across this from Quaker Universalist Fellowship (USA) re-published in 2017: https://universalistfriends.org/resources/universalism-and-religions