An Interview with Nobel Prize-Winning Author Jon Fosse

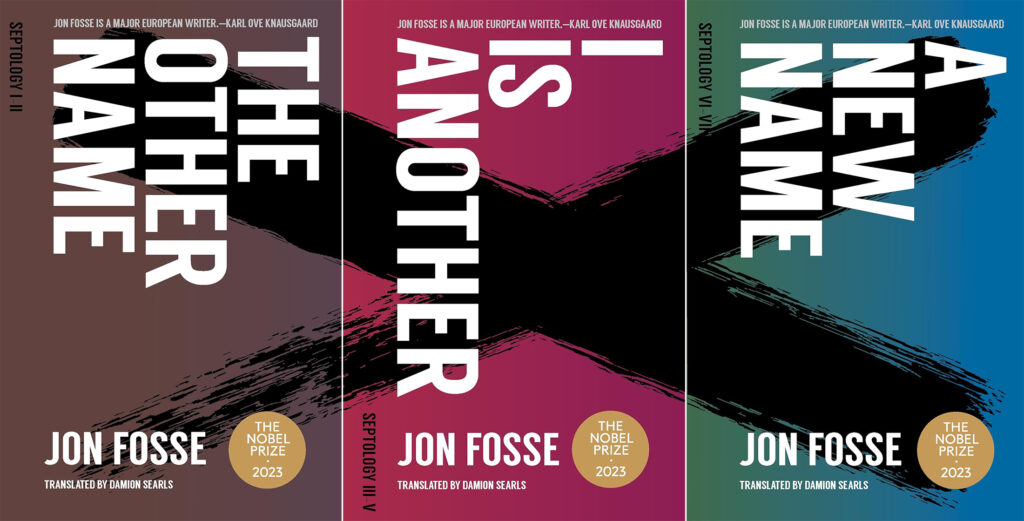

Last October, Norwegian author and playwright Jon Fosse was awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature, which recognizes a writer’s entire body of work. In 2022, his novel A New Name: Septology VI-VII, translated into English by Damion Searls, was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize; and the book was named a finalist for the 2023 National Book Critics Circle Award in Fiction. Centered on a pair of doppelgangers who are both painters named Asle, the multi-volume novel explores such themes as mortality, prayer, and the spirituality of art. Fosse has Quakers in his family, and he has attended meeting for worship in adulthood. He is now a practicing Catholic who views spiritual experience through a Quaker lens. Friends Journal staff writer Sharlee DiMenichi interviewed Fosse via Zoom in early February. The interview has been lightly edited.

Sharlee DiMenichi: Well, could you start by talking a bit about how your previous Quaker faith influenced your writing [in Septology] of the narrator’s view of light and darkness in his paintings?

Jon Fosse: I’m quite sure that my relation to the Quakers has been very fundamental for my writing and for me. The concept of the Inner Light, the way it relates to a Norwegian painter named Lars Hertervig [1830–1902] . . . I’ve written a novel about him called Melancholia. He was called the painter of light, and he’s a relative of mine, many years ago. He was a Quaker, and my grandfather was also a Quaker. He wasn’t organized, but he considered himself as a Quaker. So in a way, I grew up with this way of thinking, with the Inner Light as a very central concept. And later on in my 20s, I took part in Quaker meetings. In Norway—I don’t know what you have. We are just this quiet—we sit in this quiet circle.

SD: Oh, yes, that’s similar to our unprogrammed meetings in the United States as well.

JF: Yeah, we keep silent. And if you have something to say, you say it—or the best, you just keep quiet. This way, the trust in silence, that you can perhaps hear the voice of God in silence—I’m quite sure that’s crucial for my way of writing and has been for quite many years.

To me, writing is listening. And I hope at least that this God in me helps me to hear what I’m to write. And that’s just through the silence. I don’t hear any voices, of course, but I listen to the silence. And the silence tells what to write and what I’ve written before. So my earliest novels, they were very black, kind of heavy metal thing. But my later novels are closer to the music of Bach, I would say, in their composition and the way that I repeat it. But even they are basically written as a kind of literary music. Of course, it’s not music, but it’s—language also has musical qualities, and I use them for all they’re worth, I think. A long novel like Septology is a kind of composition. It’s the muse, the flow, the rhythm I guess is the right word. It’s completely crucial to it.

I feel like a Quaker still in many ways, but I’m a Catholic now. I converted to the Catholic Church for various reasons, but to me, I experience the mass very much like a Quaker meeting. You have these liturgical texts repeated again and again. I prefer the Latin mass, if I can choose that. And then I don’t understand all of it, just a little bit here and there. So in a way, this ritual element becomes also a kind of silence. The meaning is repeated again and again and has been for 2,000 years. So that traditional meaning, somehow it says nothing. It becomes a silence. So the silence is coming that way. And I guess in my fiction, in my prose, it’s the repetition that somehow lets the silence enter my writing. And it—this is also crucial for the rhythm—these breaks, these silences, these pauses in my plays—it’s easier to see in my plays to understand what I’m trying to say.

SD: So you talked a bit about the role that silence plays in your current spiritual life. How did that evolve when you left Quakerism?

JF: I have never left Quakerism, in a way. I go to the mass now, but as I tried to say, in a way, I experience the mass—to a large degree, the silence, the presence of God, I also experience in the Catholic mass. Perhaps it shouldn’t be like that, but I do. To me it’s like that. So I was never an organized Quaker. I thought that there was something un-Quakerish about being an organized Quaker, if you know.

SD: I see.

JF: I took part in the meetings in Bergen when I lived there, the second biggest town in Norway. Now I live in Oslo, and the Quaker communities both in Bergen—and there we were four or five persons normally, perhaps six, only that. I guess they are around 10 or 12 in a normal meeting here in Oslo. All in all, in the whole of Norway, there are only 150 Quakers organized. So it’s a very small community. And I felt I needed something bigger and stronger, in a way, to support me in my life. Because of that, I went to the Catholic Church.

The man who taught me a way to believe in a Catholic way was Meister Eckhart, the mystic. And if you read him, you will see that in the twelfth century, he wrote almost exactly the same as George Fox did in the seventeenth century but 500 years earlier. And he was a Dominican, a heretic of course. I am kind of a heretic in the Catholic Church, but they are very happy to have me as a Catholic. The pope, Pope Francis, sent me a personal letter when I got the Nobel Prize.

SD: Wonderful, oh my goodness.

JF: Yeah. That was very good. It almost brought me to tears. It was very touching—because I am, in a way, kind of a heretic. I’m also divorced, something you shouldn’t be as a Catholic. So they used their grace to let me into their community.

SD: So you mentioned that you worshiped with the Quakers in Bergen. Could you talk a bit about how you came to that meeting? And were you a member or an attender?

JF: I was, of course, a bit afraid the first time, but it was in a home in the living room of a woman living alone in Bergen. We met there, this small group. One of them was Andrew Kennedy; he was a professor in English, [teaching about Samuel] Beckett was his main thing. We were just this small, strange group sitting there. But this quietness, it came, and you could feel a kind of presence of what I call God in the meeting.

I’m quite sure that each and every human being has something of God in themselves. And in a strange way, that is what makes them completely unique, but at the same time, this quality is completely universal. So as a human being, we are completely unique, every one of us, and we are universally the same. This doubleness is very strange, but it’s true.

SD: How did the vantage point of the narrator evolve over the course of writing Septology?

JF: When I’m writing, as I said, it’s an act of listening. I started writing this novel in a castle in France that had belonged to Paul Claudel, the famous French poet and also Catholic; it belonged to him many years ago but now to his family. I was invited to go there, and I started writing this novel there. By then, I had written for many years, almost only plays, and I decided to quit writing plays. I wanted to write what I call slow prose. A play needs a kind of intensity, and I wanted to let the language flow in another, slower rhythm, but that was all I knew. It’s not any conscious decision about this or that. I feel that at least when I’m writing a novel, I’m establishing a kind of universe that has thousands of rules, and I have to listen to these rules and to follow them. I can’t formulate them. There are too many and too complicated for me to formulate, to tell them. Each and every part begins with the narrator saying, “And I see myself . . .” Then it goes into the mind of only one other person, and that’s the second Asle. Otherwise, he sticks to the “I” of the novel.

So what constitutes this novel to a large degree, at least as far as I can tell, is the way that language of time is used in the story, the way it goes back and forth. Now you can suddenly experience something that happened long ago in the past, many years back. The time is mixed; it becomes, at least to me, more like a moment, a moment stretched out like that. So it covers a whole life in a way, in these seven days that the main story takes.

SD: What were some of the most attractive aspects of Quakerism for you? And what are some of the most compelling aspects of Catholicism?

JF: As a young man, I left the Norwegian Lutheran Church as soon as I could, at 16, because I thought it was rubbish. I couldn’t stand it. And then I didn’t belong to any kind of—I had no religious connection. But I knew about the Quakers, and I read more about them and I learned about them. But as a young man, I called myself an atheist. What changed my way of thinking about it was, in fact, my own writing. Where does it come from? When I think about other writers and composers, the music of Bach, where does it come from? How can you explain that in a materialistic way? No, you can’t. Then that spiritual space, or what you call it, opened up for me. And this is an unseen thing, of course, this spiritual space. But you can feel it, and you can know it when it is there. At a certain point, I only knew that it was there, but I started to think about it as God, this unknown.

And then it wasn’t that long to come to this kind of understanding of the concept of Inner Light and to reach God, through science in a way. To me, it was and it is obvious. It became completely obvious to me. So it is. That’s the truth for me. And it still is. Even when I go to the Catholic mass, as I said, these liturgical texts are repeated again and again. And then they have their holy moment, the Eucharist, when you feel this presence—at least I do—of what I can call God during the Eucharist in a similar way that I could also feel the presence of God in a Quaker meeting. Not every time, but in a good meeting, in a good Eucharist, it’s like that. So it isn’t that different.

They are, in a way, on the extreme side. Catholicism is like a pageant with processions and, you know, all this. And with Quakerism, you remove all of this outside stuff. But they exchange themselves, and, in a way, meet. And to me, it was also a personal need, by being an alcoholic, to tell the truth. It was very hard. I had to quit drinking with a lot of help from medication and my friends and my family. And I managed, but I really felt I needed something strong to connect to, and at least in Norway, the Quaker community is small and fragile. But it was a great thing to join this 2,000-year-long tradition of Catholics and a church that’s spread all over the world.

The word catholic means “general”—that’s one thing to, in a way, take everything into itself. And at least in Norway, we are also few Catholics, Norwegian Catholics. We are only perhaps 5,000 or something like that, but there are many Catholics all in all in Norway, but they are from Poland, most of them, or from the Philippines. They are immigrants or guest workers or so. But at least it’s a very long tradition. The mass is celebrated several times each day. Even in Oslo, you can go to a mass at eight in the morning or in the afternoon or in the evening. You can go to a mass wherever you are. The liturgy is the same, the words, so I feel like I connect in a very strong way to a 2,000-year-old tradition, saying that it goes back to Christ, to Peter. He was the first bishop or pope. It’s the center there. It’s the mystery of faith. It’s the most central Catholic concept. The mystery of faith, in my view, is also a very central concept to understand the way I believed, or believe, as a Quaker.

SD: Which Quaker writers most influenced you?

JF: It’s hard to say. I would, in fact, say something completely wrong. It’s Meister Eckhart. He was, of course, not a Quaker because he lived in the twelfth century, but he was thinking like a Quaker. Then it’s the paintings of my relative, Lars Hertervig, who came from a Quaker family, and my grandfather. But if you’re into literature, as I’ve been my whole life, and art, for me, it’s so close to this, to science. A great painting, for instance, cannot tell—pronounce a word—but at the same time, it’s telling a lot, a lot, a lot in a silent way.

So you understand that each and every human being has a unique value. And this is, at the same time, the most general and worst part of this human being or of all human beings. The concept of the Inner Light also becomes, in a way, obvious. Eckhart speaks about the sparkle. He uses different concepts or words, but the sparkle he’s using the most.

And these paintings of Lars Hertervig, in Norway they call him the painter of light. The way he paints light is remarkable. He lived with a mental illness by the way, and spent most of his life in an asylum.

SD: What would you like to add?

JF: There are so many paradoxes in life, and Christianity is full of paradoxes. You can’t make it a rational system. Belief isn’t a rational system, as little as art is. So I accept that I can live with a lot of contradictions and still be as a Catholic and even at the same time as a Quaker. That’s the basic thing.

1 thought on “Jon Fosse: “To Me, Writing Is Listening””

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.