FJ PODCAST SUBSCRIPTION: ITUNES | DOWNLOAD | RSS | STITCHER

It was an ordinary house in an ordinary middle-class suburb in Erie, Pennsylvania, yet I was somewhat apprehensive, as a complete stranger, to ring the doorbell. When the door opened, I was greeted by a woman in her 60s I’ll call Phillipa, whose bright smile and brilliant blue eyes immediately told me I was in the right place. Philippa is intellectually disabled and has no language, but her welcoming hospitality was unmistakably beautiful. She has lived in this home for 28 years. I then met Sam (I am making up names for these very real friends I made that day), a man in his 40s with a boyish smile and engaging enthusiasm who with limited language told me of the jobs he had in the kitchen and around the house. There were four “assistants” in this house, one for each of the intellectually disabled persons who live there, called “core members.” The assistants helped me understand some of the language I had difficulty following, but filtered very little of the experience I was having, just letting me be there as a guest in the house.

It was late afternoon when I arrived, and John, who is in his 50s, was in the kitchen preparing a meal of spaghetti and meatballs under the supervision of Camilla, another assistant. John has more language than the others, in fact speaks very well, and can do some writing and artwork, loving to draw owls, which are celebrated by the household. He also plays some Rodgers and Hammerstein tunes one-handed on the piano. Judith is a relatively new core member of this home and is a bit less forthcoming than the others. For many, it takes time to realize they are welcome, safe, and loved.

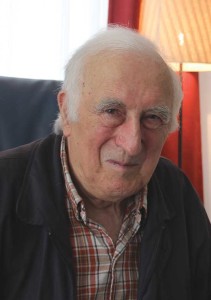

The house belongs to an international movement called L’Arche, founded in France on August 4, 1964—the very day on which President Lyndon Johnson addressed the nation about the Gulf of Tonkin incident. I cannot imagine two more antithetical actions performed on the same day. L’Arche’s founder, Jean Vanier, had been a philosophy professor at the University of Toronto, who on that day, 50 years ago, invited two intellectually disabled men, Raphaël Simi and Philippe Seux, to live with him in a house he had bought in the town of Trosly-Breuil, northeast of Paris.

Vanier did not set out to start a movement and says he had no idea of the implications of what he was doing; he was merely following Paul’s advice to the Corinthians, “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong, God chose what is low and despised in the world” (1 Cor. 1:27–28). Taking that leap of faith was but a beginning of many such leaps in the dark, figuring out how to relate to these two men as persons: as friends to communicate with, work with, pray with, have fun with, to receive from, to love. Gradually this experience began to mean more to him about the basic humanity of each person, about how being conscious of one’s own weakness and of the weakness of others leads to trust, community, and strength. An anthropology and theology of relationship that is basic to humanity and spirituality grew in that context and became contagious.

Vanier began his work on two foundations. Following Aristotle, he believed that friendship must be a relationship between equals. Following the Gospels, he believed that accepting and acknowledging one’s own humiliations and weaknesses opens one to compassion with the humiliations and weaknesses of others. This uniting of Aristotle and the Gospels is paradoxical, and the vitality of this paradox drives much of the richness, the depth, and the appeal of L’Arche. With Aristotle, Vanier believes every person needs self-confidence, a sense of accomplishment, and self-worth; with the Gospels, Vanier believes that the humiliation of Jesus’s crucifixion and the humble acceptance of one’s own weakness are the way to relationship and connection. As an Aristotlean, Vanier promotes fun and enjoyment. As a follower of the Gospels, Vanier promotes gladness and joy. It is notable that Vanier plainly advocates fun and playing around as integral to the L’Arche project. He says that he has learned this from core members. Core members invite assistants to slow down, to take time to laugh and enjoy cleaning up, washing dishes, getting bathed.

The house in Trosly remained small; other houses of similar size grew into a colony; and the movement gathered momentum, so that today there are 140 communities called L’Arche in 37 countries throughout the world. The name L’Arche refers to what Vanier calls “The Ark of the Poor.” The house I visited was one of several others in a colony, the core members and assistants of which meet together in a central location on a regular basis for a planned program and for lunch. All of these houses must pay attention to federal and state regulations for group homes, and they receive public aid through a variety of programs as well as private funds from charitable groups.

Originally, L’Arche was a Roman Catholic movement, but as it grew, it became apparent that other faith groups could grow through practicing L’Arche’s basic principles. Currently there are groups with Christian, Muslim, and Hindu orientations, yet in all homes people of all religious faiths as well as agnostics and atheists are welcome as long as they accept and support the faith of other members and assistants. The international and ecumenical success of the movement has demanded the establishment of coordination and communication across the world; thus the regional and international offices of communication and coordination have increased. Though bureaucratic necessities have grown, the movement has adhered to its basic commitment to having one assistant for each core member as often as possible. My personal experience in L’Arche had confirmed that fact.

By refusing a privation model that denies those with intellectual disabilities of their basic human rights, L’Arche is a unique expression of what Quakers call the testimony of equality. Much has been written about the movement, most notably by Jean Vanier himself and the priest Henri Nouwen, who wrote Adam: God’s Beloved just months before his death in 1996. Nouwen stated that his relationship to this core member of L’Arche gave him a new appreciation of what it means to be loved.

Vanier writes in a simple and straightforward style that manifests the depth and richness of his life and thought. His books number over 30, and they mostly tell of the human path from loneliness to encounter to relationship to inclusion to community to the ultimate confrontation with the mystery of our humanity in the ever-arriving presence of God.

It is a paradox that by not offering a program, Vanier has set conditions for a program that has grown worldwide. L’Arche is a peace movement that by transcending politics offers freedom from individualism, materialism, and tribalism by demonstrating the bare bones of what it means to be human. It appears to me that we Quakers ought to examine this movement and move with it.

I am an attender at Community Friends Meeting I’m also a birthright friend but since joining Atlanta Friends Mtg, haven’t seen a reason to transfer my membership here. I’ll admit, I feel ‘less than’ I was before and so haven’t joined. Part of the reason is that once I join, I’m COSTING the Meeting more money paid to our yearly meeting. I can’t, in good conscience do that. I feel I COULD earn money if I did Quaker Wedding Certificates again, or ANY type of calligraphy, but my guardian won’t give me the tools of my trade. Now I have bed bugs again, and I don’t want my paper to be infected.

*sigh* the other reasons are that if I’m not working, I don’t feel I have any value as a person.