The Unwritten Norms of Speech and Silence

One by one people enter the room to take their seat for meeting for worship. At their feet is the bare wooden floor and at their back, a warm Mexican blanket is waiting to hold them. They arrive with a mix of emotions. Some are pensive, uncertain, and feeling an odd combination of anxiety and anticipation. Others are calm and at ease. Some are Quakers: lifelong Friends, attenders, or strangers visiting from out of town. Many are passionate about various social issues. All are curious, brave, and bruised by life.

This is a familiar moment for many Friends: arriving and settling at the start of Quaker worship. However, too often, the deeper meaning and tenderness of the moment is lost in the hustle energy it takes to stop our lives and get ourselves to Quaker meeting. As the unprogrammed meeting for worship unfolds, the brave at heart offer vocal ministry, speaking eloquently and using just the right metaphor borrowed from nature to state to their concern. Silence falls, and then someone else rises to speak, then another and another. As person after person rises to offer vocal ministry, we meander with each speaker from a political conviction to a query about the nature of faith in general to a call to action. All of this is held in the silence.

I’ve come to understand that when I arrive at Quaker worship, I bring my whole self, both the fullness of my identity and my life experiences.

When I began attending Quaker worship, I brought with me a robust faith life that informed how I listened, how I sat in the silence, and how I observed my own thoughts and feelings. I attended Catholic schools for 12 years. Culturally, I identify as Black, of Afro-Cuban descent, a first-generation American; and as a heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied, highly educated woman, born into poverty in New York City and now living in the middle class north of Philadelphia. My mother and grandmother were Catholic. I was a member of the Ethical Culture Societies in Philadelphia, Pa., and Princeton, N.J. I have studied and practiced kundalini yoga within the Sikh community for the last 19 years, and I am an ordained Buddhist lay dharma teacher in the Plum Village tradition founded by Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh.

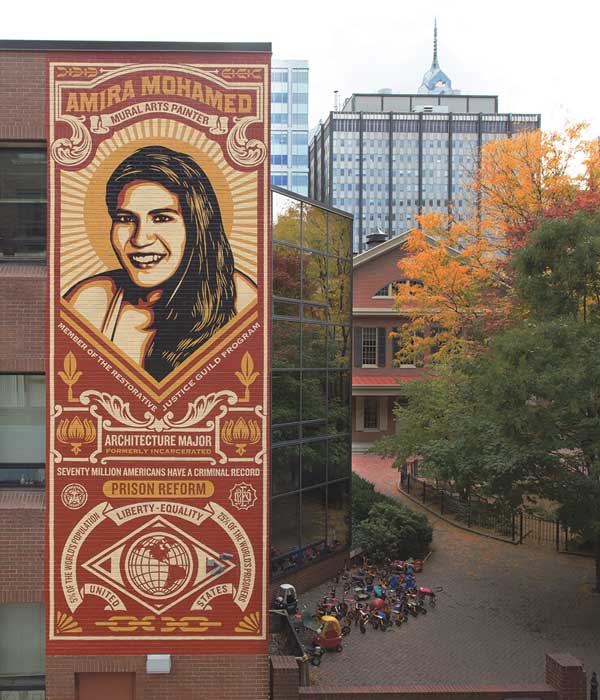

I’ve come to understand that when I arrive at Quaker worship, I bring my whole self, both the fullness of my identity and my life experiences. As a person who identifies as Black and as a woman, largely operating in the dominant White culture of Quakerism in Philadelphia, I’ve become aware of the unwritten norms that underlie Quaker faith and practice—and worship in particular.

Trust and Learn from the Silence

When I first joined a Quaker meeting and was curious and open (I still am), I was taken aside by Friends seeking to “help” me understand the climate and culture of the meeting. They were the elders within the community: respected members with decades of experience in Quaker faith and practice. Some were lifelong Friends. Nearly all of them sat silently each Sunday on the last bench of the meetingroom during meeting for worship. I surmised that this position gave them a perch from which to take in the fullness of the meeting. Early on, a stalwart of the meeting, a gray-haired matron in denim and woolens, approached me and cautioned: “Don’t speak unless you can improve upon the silence.”

My body froze, and I felt deflated. I became angry and then curious.

Little did I know that this was a “quiet” meeting whose unwritten creed was to privilege silence. It set a very high bar on the use of vocal ministry, so any speech must rise to the level of the grace and elegance of silence.

I adore silence. However, as a Black woman, I am aware that for Black, Indigenous, and communities of color (and among other marginalized groups), silence has been a form of oppression that cuts us off from sharing our voice and agency and more. A reframe for those quiet meetings would require us to explore questions about speech and silence. How do we teach about vocal ministry? What messages about silence and speech do we send to seasoned Friends and newcomers? How might silence inadvertently encourage greater distance among Friends? What is the right balance?

Speak with Clarity

When I feel myself called to vocal ministry, I often feel uncertain, unpolished, or raw. This feeling can be at odds with a superficial, ego-driven desire to sound coherent, together, and meaningful. I’ve struggled with being faithful to the voice within me that says, “Rise from your seat and speak,” and the voice that wants to control the process of speaking. Longtime Quaker writer and poet Judy Brown offers wise advice. As both a Friend and a friend, when Judy speaks either in her many books on leadership or through her poetry, I listen. She says that the essential voice that may be in touch with the “shy soul may not be practiced, smooth, slick. It may be confused, emotional, embarrassed, in the midst of experiencing and sorting things out.”

If we are speaking from the voice of the shy soul—the elemental self, the Spirit-led self—our words may very well be unformed and misshapen. A reframe might be as Judy Brown advises: “Be willing to be raggedy.” Speak your truth: clarity of thought is not the hallmark of Spirit-led vocal ministry.

Intention Accompanies Effect

There are times in meeting for worship (and elsewhere) when I feel downright rageful: triggered by someone’s good intentions that either fall flat on me, leave me scratching my head in curiosity, or shaking in the heat of my own anger. As a mindfulness practitioner, I’ve learned to handle strong emotions. I know to breathe, calm my body and mind, self-regulate, notice what is happening within me, feel the fire of the rage, and offer compassion to myself. When I am at my best I can offer compassion to someone else.

Not only do we need to learn skills to care for ourselves and our emotions in the moment, but we also need to understand that those good intentions, even when Spirit-led, are not a license to ignore their unintended impact on others. Even as we gather for meeting for worship and offer Spirit-led vocal ministry, this too is within a broader societal context of structures, systems, and institutions that further oppression and racialization.

Not only do we need to learn skills to care for ourselves and our emotions in the moment, but we also need to understand that those good intentions, even when Spirit-led, are not a license to ignore their unintended impact on others.

A reframe for Quakers would be to take a deeper exploration of our good intentions. How do our intentions affect others, either intentionally or unintentionally? How might we look deeper at our intentions and align them with our actions? When might our intentions not align with our values? What do we do individually and as a corporate body when this happens? How might our good intentions further support our own implicit bias?

These unwritten creeds form a subtext that may be understood by some Quakers and unknown to others. Without awareness and critical inquiry into these unwritten Quaker codes of behavior, we risk isolating and distancing whole groups of people: newcomers, marginalized people, Black people, Indigenous people, people of color, and more. As Quakerism in the United States seeks to address increasingly dwindling numbers of Friends, reframing these unwritten codes is crucial to creating an atmosphere that truly welcomes and is inclusive for all.

Brava! Well said. Sometimes the more inclusive welcoming also needs to extend more openness to any non Quaker person of any color or background. Quakers in other areas where I lived come off as elitist, wealthy, excluding and their schools as too expensive despite scholarships to include certain kids, black, white or whoever. So intentions of old need reevaluating for today’s diversity of persons, ideologies, needs, inclusivity in full voice and seats at the table for all.