Quakers are nice people. We’re known for that. We smile at people we pass on the street. We clean up after ourselves. We say “please” and “thank you” to those who clear our tables or carry our luggage; we recycle, and we tip.

But niceness has limitations and pitfalls that we ignore at our peril. I submit that in some ways niceness is eroding the Religious Society of Friends: it seduces us away from practices that could sustain us, and in certain ways it does actual harm. Many Friends have observed that our meetings are graying, shrinking, and losing vitality. Getting a handle on niceness could help to turn that trend around.

The problem

I assisted recently in the middle school classroom at a large and prominent meeting. The day’s activities included a game-show-style Quaker quiz that engaged one sixth-grade Friend in particular. Having been raised in this active meeting, he knew his Quaker principles and was eager to learn more. But to every question that began with “Why do Quakers . . .” he turned to niceness as the reason. Why do Quakers work for equality? To make everyone feel good about themselves. Why is community important to Friends? So no one’s feelings get hurt. Why do Quakers conduct business the way we do? Because everyone’s opinion matters. In his every answer, there was a modicum of truth and a chasm of missing information. This boy was evidently being raised in a religion he thought of as the Polite Society of Nice People.

Now, I’m not advocating a world without niceness. It does a lot of good in the right places, and its absence can be devastating. If the only other option is violence of some kind, then niceness is a reasonable choice, and in certain situations everything depends on niceness. When it is not important to continue a relationship or to deepen an existing one, for example, niceness can be the cool-headed usher with the flashlight who shows everyone safely to the exits of a burning theater. Leaders of nations in conflict may avert war by being nice to each other. Successful mediation requires niceness, as do many business transactions. Niceness is as important to neighborly relations as fences are.

However, I do want to distinguish niceness from kindness, which is another thing entirely. Kindness comes from love and results in closer relationship; it comforts and joins together; it is related to compassion as well as self-sacrifice, service, and respect. When we behave kindly, we feel its effects as keenly as do those to whom we’re directing our kindness. Sometimes it’s hard to muster kindness, but when we do, it lifts us above the source of our resistance and gives us a broader and deeper understanding of ourselves as well as others. In contrast, niceness comes from habit and sometimes even from fear, discomfort, or aversion. It’s easy, and it makes us feel comfortable. It lets us keep our preconceptions about others. It masquerades as caring while resisting intimacy; it distances by conveying benign disinterest. Niceness implies, “I’m keeping things superficial because you have nothing of value to offer me.” When we’re being nice, we remain separate and may even experience a sense of superiority. Niceness is a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

These are some things nice people don’t do: Contradict. Challenge. Intrude. Brag. Pry. Discuss “private” things. Ask “too much” of others. Walk toward conflict.

There are two places where niceness does not serve us as Friends. One is among ourselves; the other is in our engagement with the world. And since that pretty much covers everything we are and do, it is essential that we learn to recognize when niceness undermines all that we cherish, so that we can use it with intention when it’s appropriate and avoid its allure when it’s not.

It is essential that we learn to recognize when niceness undermines all that we cherish, so that we can use it with intention when it’s appropriate and avoid its allure when it’s not.

Niceness within the Religious Society of Friends

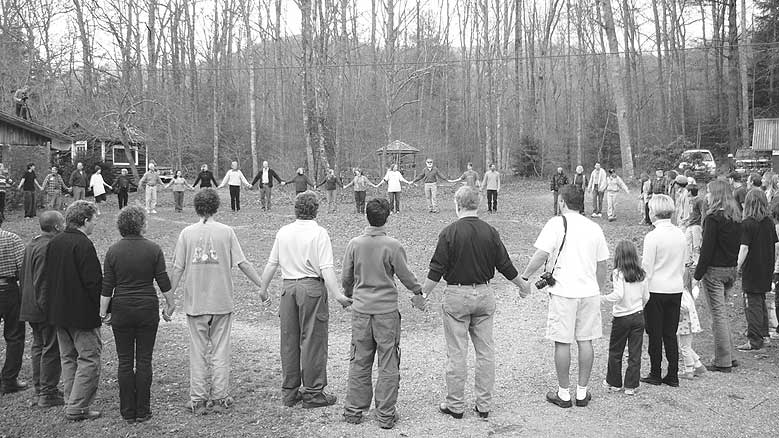

Years ago I visited an inner-city Protestant church in Cleveland, Ohio, whose minister could have held his own on any comedic talk show, the kind where truth is told. His topic was the Body of Christ that lived right there among his congregation. It was tired, frayed, old, and exhausted, he said. Oh, people were coexisting amicably and tasks were being tended, but the Light was gone. He imitated the way his parishioners greeted one another: “How you doin’?” Lively, upbeat, nice, the inflection rising cheerfully, the demand for the requisite answer (“Oh, fine thanks, how about you?”) built in. What the Light needed, he said, was the greeting his aunt used to offer everybody who passed through the back door into her kitchen: “How you DO-in’?” Warm, close-up, slow, the timbre falling at the end into a tight lock of the eyes.

Do we care enough to push aside the veil of niceness and know one another? To enter private space and share how the divorce is coming, what the doctor said about those test results, how sobriety was challenged last night, how anger has taken us to a dark place we’re struggling to find a way out of, how it’s been months since we felt the presence of God? Do we have that level of trust among us? Moreover, do we recognize that kind of conversation as the water in the garden of spiritual life?

In 1657 George Fox urged “Friends every where” to “know one another in that which is eternal” because “this differs you from the beasts of the field, and from the world’s knowledge” (Epistle 149). He went on to say that meeting together in the Light saves us from “run[ning] into the earth,” from “grow[ing] weary and slothful, and careless, and heavy, and sottish, and dull, and dead.” In other words, our fellowship in the Light keeps us from forgetting what it is that makes us Friends. Togetherness in the Light keeps us in the Light.

Knowing each other in the eternal is a far cry from niceness. It requires doing all the things that niceness forbids. It means being vulnerable, reaching out across difference and conflict, laying bare the most tender of inner spaces, and trusting. It may be the most difficult thing we ever do. But Fox urged this on us because the very practice of such intimacy is a spiritual discipline. He didn’t say we should know each other in this way because it builds a pleasant community, or because it makes us comfortable, or even because it unifies us—which it sometimes does and sometimes doesn’t, at least in the short run. He said that without this spiritual discipline we lose our connection with the Light. Knowing each other in the depths beyond niceness is as much a testimony of Friends as the other practices that keep us faithful.

The secular world runs well on niceness, but the Light in which we meet demands attention to a much deeper level of ourselves and each other. We sell out to niceness when we nod politely and walk past those from whom we feel different, when we agree to serve in a capacity to which we don’t feel fully led, when our committee and business meetings are comfortably conversational rather than worshipfully attentive, when we choose the path of least resistance.

In one meeting with which I’m familiar, a clearness committee was formed to discern membership for the partner of a current member. For convenience, since everyone lived at some distance, the committee met at the meetinghouse before worship. When asked why he sought membership, the candidate replied that it was because “Quakers don’t have a creed, so they don’t tell you what to believe.” Although members of the committee saw that this answer revealed a desperate need for education, instead they resorted to niceness, nodding politely and making a quick thumbs-up decision so as not to be late for worship, risk offending the member-partner, or inconvenience everyone with another committee meeting.

Much was lost in this moment. The committee members lost integrity; the new member missed out on exploring further; everyone in the room lost the chance to know each other better and to experience the assistance of the Light in bringing them to clarity. Perhaps most significantly, the meeting lost the opportunity to expand its ranks of members who are fully aware of the meaning of being a Friend, and so the Religious Society of Friends credentialed an ambassador who would carry his inaccurate understanding out into the world. In the blink of an eye, niceness eroded the future of Friends.

Discernment is not a nice process. When we navigate inwardly to speak a message we receive during worship, we’re bushwhacking through a jungle of ego, self-deception, neediness, self-doubt, and all kinds of other shadow motivations in order to reach the raw light of truth. Niceness to ourselves subverts the whole meaning of this process, not to mention the result. When we listen together for the sense of the meeting, we subject our corporate decisions to a relentless and exacting review. Sometimes we must enter dark places together. Kindness, gentleness, forbearance, forgiveness, and patience all have a place in this process, but niceness does not.

If we were to shift our interactions consistently from niceness to kindness, imagine how our worship would deepen, our love for one another blossom, our sense of ourselves as Friends settle into the depths of our nature.

How often do we wonder why visitors haven’t returned, saying, “But we were so nice to them!”?

Niceness in our outreach

I recently enjoyed a long conversation with a very committed Friend I’ve known for over 20 years, and he told me the story of how he came to Friends. He was raised with no particular religious belief, but as a teenager, he went to Quaker meeting with a neighbor now and then “because her daughter was cute.” One of the men in the meeting, someone he describes in retrospect as “an elder,” invited him for a walk one day after worship, and together they left the meetinghouse and strolled down the street. The elder asked how he was, and the teen launched into the usual kind of answer: how well his soccer team was doing, subjects he liked and disliked at school. The man listened for a bit, and then during a pause, he said, “No, really, how’s your life?” The revelation hit this teenage boy with the force of conviction: “these people are interested in the things that matter.” He felt fully and genuinely cared for, and he knew this was where he belonged.

How often do we wonder why visitors haven’t returned, saying, “But we were so nice to them!”?

In his keynote address at the 2015 Friends General Conference Gathering, Parker Palmer described the Religious Society of Friends’ urgent need for renewal. He cited the fact that our numbers decreased by half between 1972 and 2012. “Statistics like these—along with the rising median age of meeting membership—have some sober observers suggesting that the Quaker community might end its run by the close of this century.” However, he observed that the world is full of people he characterized as hungry for “treasures” that Friends have in abundance: “treasures sometimes hidden from us by our familiarity with them, and too often hidden from others by our reluctance, even inability, to talk about them.” To the extent that that reluctance comes from scruples about seeming to be bragging or treading on sensitive ground or invading the listener’s privacy, niceness is contributing to the problem.

Palmer also notes that some of the challenges to expanding the Society of Friends are built into its beliefs and practices. In particular, he says that “its open form of worship—and its belief in continuing revelation—can easily be mistaken for ‘anything goes.’” Liberal Friends ourselves promulgate this untruth by giving newcomers the impression that we have no particular creed. It’s not nice to tell your guests what to do and say, so we roll out what we think is the welcome mat by assuring newcomers that all beliefs are valid here. But this is no more true than so many other platitudes that niceness spawns. The least-common-denominator understanding of who Friends are is a misrepresentation to others and erodes our own sense of identity. In fact, Friends do have a set of commonly held beliefs, practices, values, and outlooks. Pretending otherwise in the interest of drawing in newcomers highlights the way in which niceness can verge on deceit.

This particular expression of niceness ironically confounds our desire for increased diversity. It may seem as if a “come as you are” invitation would encourage diversity by welcoming everyone, but as Adria Gulizia points out in “Greater Racial Diversity Requires Greater Theological Diversity” (Friends Journal Jan. 2019), this kind of relativism “fit[s] neatly with white, middle-to-upper class, liberal culture” and alienates those who, like many people of color, hold to more traditional theologies. Those very theologies are alive and well among Friends, but at least partly from get-along niceness, we keep them under wraps. Similarly, young people seeking a religious and spiritual home may be looking for something more than the “anything goes” relativism that the secular world provides in abundance. Our scruples about being too forward or too intrusive may prevent us from conveying who we really are. As a result, we fail to provide a true welcome to those who might enrich our community immeasurably.

When people are hungry for Truth, niceness is the spiritual equivalent of a handful of potato chips. In actuality, Friends have a nourishing banquet to share. If, instead of niceness, we offer kindness, respect, attentiveness, genuine interest, and transparency about our own experiences in the Light, then we show true hospitality and demonstrate the kind of spiritual home we have to offer.

Forward without niceness

A secular virtue, niceness is a Trojan horse among Friends. Its familiarity may be reassuring, but easy comfort is not conducive to the kind of spiritual encounters that Friends seek. When we open to the Light, what it illuminates may not be nice. It may be challenging, inconvenient, discomfiting, humbling, even disruptive; it might contradict things we or others have held to be dearly true. It might also be dazzling, inspiring, uplifting, deeply moving, transformative. Friends’ experience tells us that it will always be worthwhile.

Just as niceness can obscure doorways to spiritual transformation, it may also hinder us from living the courage of our convictions. It can deprive us of the empowering experience of witnessing to the world who we are as Friends, in turn depriving others of the chance to learn what we know. The alternative to niceness does not have to be meanness, cruelty, or anything of the sort. Living and breathing who we are, even at the risk of being vulnerable or intrusive, can be a gracious and ultimately unifying act.

This is right on. So often Friends are afraid of using terminology that might offend or get upset because someone expresses a belief with passion. Early Friends were alive with Spirit – their outreach and evangelism about the Light and Spirit is revitalizing Spanish speaking congregations as more of their writings are being made available in Spanish. Speaking our truths attract those who are seeking.

I love this article. I am so tired of chat. I welcome the insight that our theological relativism “fit(s) neatly with white, middle-to-upper class, liberal culture” (quote from Adria Gulizia). I write as one who left Friends in my teens for its theological indistinctness and embraced Evangelical Christianity. This gives me an inside knowledge of the creed, from which I want to say something. I eventually found that the image of God enshrined in this creed does not accord with my understanding. I returned to Friends in my 50s, specifically valuing its theological relativism.

I long for inclusiveness. I am really saddened that my liberal stance is offputting to others. As a Friend, I am committed to seeing God in everyone. I think this means I have to accept that they believe as they do, never mind if I believe differently. Now can an Evangelical Christian say the same? . Embedded in the Evangelical creed is the imperative to save souls. There can be no equality between the Evangelical and the one who needs to be saved. The Evangelical has the answer that I need. Though it is not a personal arrogance it is a theological arrogance. How I used to hate being called arrogant! It is impossible for the Evangelical to accept that I believe as I do, never mind if my belief is different from theirs. My conclusion is severely uncomfortable. I cannot embrace Evangelical Christianity for itself, nor for the sake of inclusiveness.

The article is an important message in a world where many leaders are teaching the terrible theory of following without questioning, when we respond truthfully, albeit kindly, we can never walk without thinking.

Thank You,

Renee Ducker,

Whiting, N.J.

I was a sincerely devoted Quaker but had to leave because my meeting would not talk to me about issues I felt needed to be addressed. It became that I was wrong, or too sensitive, or should talk to a therapist- when it really was necessary to the health of the meeting! I am a bit of a ‘barometer’ or intuitive – picking up on things that can take us ‘off course’ and I to using ideas wrongly. But because I was not a birthright friend (none were in our meeting, but when one showed up, they were immediately given special privilege!).

I ended up studying A Course in Miracles very deeply to get at the REASON we keep ‘accentuating’ the wrong ideas in our attempt to be

Good Quakers.’ It happens elsewhere too – even/especially in ACIM groups! But at least ACIM is a path specifically to learn to uncover this way we tend to misuse what could be healing ideas.

So if we are trying to ‘be nice’ that is often ourself trying to do so so that we will appear good – or a good Quaker. Therefore, we are making it about ourselves, rather than the other person. simarly, a woman came to our Quaker Meeting and told me the Friends there caused her to feel like a nervous wreck because if she tried to help out in the kitchen, say, others would start cleaning right where she was or taking things from her to put away. It was ‘overkill.’ I even wondered if they were trying to chase her away!

ACIM explains all this. I so wanted to share it to help our Quaker meeting, but as ACIM explains, the Friends allowed me to have the meeting, but refused to open their hearts or mind to understanding my purpose. So it was a double message!

What Quakers need it to be open as much as possible to new ideas. That is why Quakers got established in the first place; George Fox did not buy into the understanding of scripture that the Church of England did. But we are being called to continue to open to ideas that will truly heal our world and humanity. A Course in Miracles is one idea that truly helps us see “how to be truly helpful” and so well worth investing in understanding it so our meetings can be dynamic. Rather than ‘well meaning’ but way too static!

Modern Friends have a common praxis: we ask to be led, we open ourselves to leadings, we work at fully experiencing those leadings, and we take action based on those leadings. Our diverse theological perspectives inform us as individuals. We are free to bring our own names and understanding of the source of our leadings, which we broadly call spirit. Our common praxis turns that cacophony of theologies into a rich harmony of everyday mysticism in our lives, at best. “At best” because the “necessity of niceness” often prevents us from going wherever spirit leads.

Niceness from leading enriches the giver and the recipient. Niceness from middle-class habit deadens the soul of both giver and recipient. Those of us raised in the middle class would do well to remember, perhaps revisit, Sinclair Lewis now and then. The middle class seeks to avoid upsetting or offending. We’re good with comforting the afflicted and conflicted about afflicting the comfortable, especially in our own Meetings. Niceness is a useful symbol for the lack of spontaneity and integrity we exhibit in our lives and in our Meetings.

Yes! Yes! Yes! Thank you for the articulation of something I have struggled to put into words for a long time. Niceness and kindness are not the same thing. Niceness gets in our way. Kindness makes room for seeking, vulnerability, and truly embracing difference. Let’s lead with love, not niceness.

I too love this article. I have had life-changing revelations during meeting for worship. I have felt closer to God while sitting in the holy quiet of Meeting for Worship than any other religious setting I have participated in. There is nothing spiritually unique about me. I’m certain others have had similar experiences. Yet, we so seldom share these experiential moments of spiritual truth with each other. I’m concerned that our “niceness” may be perceived as bland when encountered by others especially young people who come as seekers when they attend their first meeting.

Early Friends attracted the name Quakers because of their tendency to tremble or quake when delivering messages. Being nice does not cause quaking. It is speaking with passion and conviction even though it may not be what is currently politically correct that is more likely to start the heart-pounding and subsequently cause the limbs to quake.

If we wish to increase our numbers we need to be so intense about our opinions and express our beliefs with such fervor that we touch the hearts of our listeners.

The problem is both deeper and wider than theology. Niceness pays dividends to those who practice it. They are seen as likable by never creating any sense of disquiet or challenge to those around them. In my meeting truthful disagreements and plain speech about them can often be seen as a negative personality trait.

Let us never forget that early on Quakers called themselves’ Friends of the Truth’ . In telling the truth about the evil of slavery ‘in plain language’ Woolman was NOT being nice to slaveholders.

A close friend of mine and I are holding a reading and discussion based on this article that hopefully will begin to address this very real and destructive vice of niceness.

Beautifully written, very needed and thought provoking. “Being nice” is especially prevalent among women and even more so in the past year when so much very- not-niceness has been spreading in quite malignant ways.’However, as you say, the opposite or antithesis of niceness is not meanness or cruelty but authenticity; authenticity with kindness at its core. Not easy to be or find, but possible for all .

As I read these words, I felt a powerful sense of coming home, coming home to an existential and enduring embrace. Thank you.

I had a nice Quaker upbringing and only in the twilight of my life have I come to the realization that niceness has hampered my interpersonal relationships. I have had few close (lower case) friends but many acquaintances. Thanks to this article I have now have a clearer understanding of my self.

Nice versus Good

Nice to me is a very weak and flimsy word. It often refers to people who are seemingly polite in an effort to please, people who placate others while hiding their true emotions. Although we can all be nice, the real truth is: sometimes we’re not. I don’t know any really “nice” persons who never disagree and always do whatever is necessary to fit into society no matter what the circumstance.

Good on the other hand is real. It is I believe what we all truly are, our basic nature, the way we were originally born and meant to be. My belief is that deep inside even the worst person is capable of love and has a beautiful soul. Sometimes we may have to dig a little deeper to see it, but it’s always there inside ourselves and others.

It is important to remember that we are all more than nice people expected to behave in forced, unnatural ways. We have the power to replace superficial niceties with genuine acts of love. We must always be mindful of the ultimate goodness that surrounds us because that is how and why we were created and who we truly are.

I’m an attender that is feeling called to join the Society of Friends, and I often feel I’m joining an organization in its twilight years. There’s a vitality in the early Friends that I read about that I struggle to locate in the meetings I’ve attended. I think this piece really dives into the heart of the matter. I’m starving for spiritual depth. I want more than one hour a week of meeting. I leave feeling satisfied but ravenous for more. Was it “nice” people who trimmed meetings down to an hour a week to satisfy our busy outside lives? I pray for increased vitality.

In Defense of “Niceness”. The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) is already a worldwide faith; by that I mean, it is found in many countries around the world, not just in “white” and affluent ones. I am writing from the Philippines. Where I live, people will usually take pains to give you directions when you ask where a certain specific house is located; a stark contrast to my experience in asking for directions among strangers in a London train station. Quakers’ niceness is a blessing in such environments (or cultures?) where smugness or indifference rules. And mind you, London Quakers are nice. I understand the author is advocating for some kind of deepening. I agree. But it is not the fault of “niceness” that we sometimes lack depth. Perhaps, our numbers are dwindling, not because we are too nice, but we seem to be timid in announcing to the world that there is such a thing as Quakerism. We no longer have the “evangelical enthusiasm” of George Fox. We always avoid looking like we are proselytizing. Fair enough. Nevertheless, let us continue to be nice; even as we speak truth to power.

Friends speaks my mind (and much more articulately than I could).

Thank you for such a strong public witness to this vital point, Ann.

I also was disturbed reading this article. Being polite and kind, the hallmarks of niceness are important in a civilized society. Quakers on the other hand have a tendency to be passive aggressive in their interactions. And this is where niceness is a problem. Quakers do not directly say what they mean. And they are often very critical of others behaviour and feel they have a higher moral stance. This is expressed in a “nice” way that can be very hurtful. It is a “holier than thou” approach to others. I am not sure what the answer is to this concern, but I will continue to be as nice as I can!